Goudou Goudou (2)

By:

November 22, 2010

Second in a series of posts.

We smell it before we find it, half shoved through a barbed wire fence as if it got stuck and died waiting for rescue that never came. It wasn’t there yesterday and death became it many days ago, so why is it there now? Bloated to bursting, as if someone shoved too much air in a blow-up dog. Feet sticking out table-leg straight. A brindle pitbull, a rare breed among the generic mutts of Haiti. We stare with confusion until someone suggests it was planted right outside our tent to spook us.

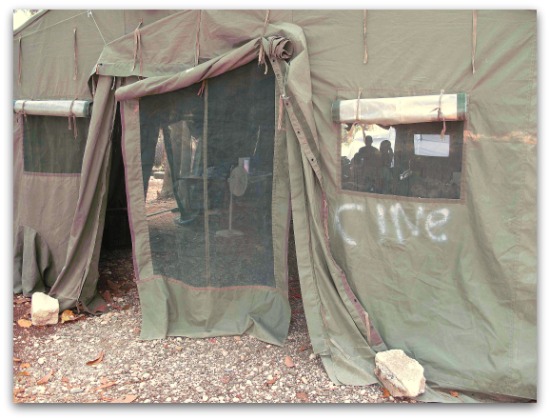

Our M.A.S.H-style army tent is in a sparse banana field belonging to a peasant agronomy group. Workers zip about in matching yellow T-shirts and do good things, I imagine. When we lost our film school to the earthquake, they let us cram the computers and cameras my students had saved from a rain of rubble into a room, pitch one tent for the students to sleep in, and a big army tent for my classroom.

Every day my students tell me stories, we develop them, figure out who to interview, and rush off on mototaxis, filming guerrilla-style. Then back to the tent to digitize the footage and watch scenes from classic films to keep the juju going. It’s muddy and hot. Chickens, pigs and children wander in and out. There’s a triage aspect to it, as if the stories we want to tell will die without fast intervention. We’re next to the airport, under an endless dust and roar of Canadian, US, Sri Lankan, Venezuelan military planes, UN helicopters, private planes carrying visiting dignitaries and celebrities.

We’re a jumpy bunch, especially when under concrete — what with a swell of rumors of another quake imminent and the numerous aftershocks that turn the ground underfoot into a roiling sea. Tents feel relatively safe. Sometimes a ripe mango hits our tent and half my students bolt, then come back in laughing nervously, sharing the juicy mango booty.

The dead dog is an event, and spawns waves of paranoia. It’s my fault: the two films I’m teaching this week are Coppola’s The Godfather and González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros. My students were astounded at the dead-horse-head-in-the-bed scene in The Godfather. Dead fishes wrapped in newspaper, severed horse heads in bed, it was a strange new vodou; mob-style stinkbomb messages. And now here we had our own bloated canine missive. Even the title Amores Perros, “Love-Dogs”*, frayed our nerves. Did someone put the dog there as a sign we’ve overstayed our welcome?

It’s too stinky and creepy to stay in the tent, so we head out to shoot instead. I take Enette and Bellegarde to shoot Clowns Without Borders at a girls’ elementary school.

We hang around in the courtyard of the school, one of the few not reduced to rubble, waiting for the clowns. There are a few pre-pubescent dudes hanging at the entrance. One has a long pink tie that knots tight at his neck, disappears under his shirt, then peeks out at his crotch, hanging long and loose like an unfurled tongue or lazy dick. He jerks around and the thing swings and flaps. The girls giggle, but it looks so innocent I wonder if I’m the only one who sees his little fashion statement as salacious.

Little girls begin to stream out of classrooms. They come in waves, like baby chicks, in blue uniforms with blue ribbons in their hair. They chirp away, the sound building like a swarm of locusts. There is a churning hum in the air; that feeling one gets just before a torrent of rain splits the sky. The chirping tsunami of blue keeps coming, drifting, settling in pools, flooding the courtyard. We’re setting up the tripod, attaching cable for the boom. Bellegarde begins to film the “anticipation” shots, while Enette searches to secure a spot where her boom can catch whatever sounds the clowns will make. There is something ominous about the neediness of all the little girls, about the dark malevolence of the air. The girls have been through all kinds of hell, and their yearning for a spot of joy is too intense.

One little girl asks me, what is a clown? I tell her they’re half funny, half scary, like the masks at Kanaval.

Here come the clowns. They cruise cool into the hot mix in a black SUV with tinted windows, leap out in bursts of color, toots of horns, faces contorted in the clown grimace that seems to command: “Laugh, dammit!” Waves of little blue girls swarm at the clowns, desperate teachers try to hold them back, and we’re buffeted about by the little girl mosh pit. We’re helpless. It’s not like you can push back at tiny little girls, and each one is innocent, it is only in their mass of yearning that they are a force of destruction. Bellegarde can’t hold the camera still and I try to help steady him. Enette is careening around in girl waves, her boom cord yanking the camera. She’s got a sly little smile on her face, which I read as part amusement, part terror.

The clowns leap and squeal and twirl umbrellas and pratfall, a lurching panic in their routines. They’re hot, their make-up streaming, costumes dirty, trying so hard, but there is something furious about their desperation to elicit laughs. The little girls’ laughter is turning into something uncontrolled, uncontrollable, their staggering, screaming joy… It’s too much. The clowns see that some little girls are getting knocked down in the rush to see them. They leap into their SUV and zoom off, the girls left squealing in confusion. I wonder if it is joy they just felt or just frustration at some kind of force-fed fun swallowed too fast to taste.

We chase after the clowns to Pinchinat, their next gig, flagging down mototaxis and rocketing through the crowded streets. At the tent camp, the people seem more prepared for clowns, perhaps because chaos reigns day and night in Pinchinat. A few men are able to form a large ring of children. They tell them to hold hands and never break the chain, keeping the crowd at bay. A hundred pratfalls, clothes changes, parades, stilt-walking and horn-toots later, the smiles are wide, spirits lift and hover somewhere above misery. The threat of a storm, looming since our discovery of the dead dog, cresting at the little-girl mosh pit, has passed.

Later, I drop off the tapes with the NGO responsible for “child friendly spaces” that had hired us to shoot the clowns, whispering to the NGO official that there’s a bit of riot footage that they may want to edit out.

Back at the school tent, the dog’s been buried, but strangely close to us, and not deep, so the stench lingers. There are rumors: we over-stayed our welcome; it was a stinking message to us to give back a little something. But nothing is certain, and it could just be a dead dog. This is normal in Haiti: swirls of rumor hit like ill winds and pass, and no one seems to care to sort out the truth; but somehow, in the suspicions and the aftermath, something is figured out. We just rarely know what it is.

* Amores Perros Wikipedia translation cliff-noted: “If your life turned out well, thank your lucky stars, if not, tell it to the dogs,” or “My life is going to the dogs,” or “It’s a dog’s life,” or if amores is all that’s good in life, and perros is misery and bad luck, then “Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose,” and ¿Qué es el amor? (What is love?): “amores perros,” or “wretched affairs” or “bad luck in love,” and “amor es perros,” i.e. “love is man’s best friend.” Love’s a Bitch Dog, Dogs of Love, or, the simplest: Love Dogs.

In other words, read into it what you wish.