Inscribed Upon the Body

By:

November 19, 2010

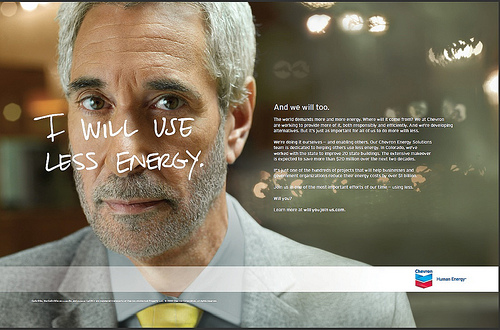

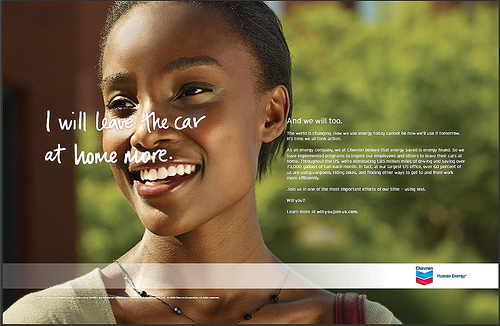

Chevron’s “I Will” campaign, still going strong in the pages of doctor’s-office magazines, here in the US, was designed — the company announced, in 2008 — to raise awareness of the importance of energy efficiency and conservation. In the ads, small-step declarations of eco-intent such as “I will leave the car at home more” and “I will finally get a programmable thermostat” are scrawled, in a folksy handwritten font, across the faces of regular men and women like you and me.

[Fifth in an occasional series cross-posted from Semionaut, a blog co-edited by the author.]

Cynics have sneered that the campaign’s secret subtext is climate change, and that by encouraging the public to use less energy, Chevron “hopes to forestall any regulation or taxation of its carboniferous products.” That may well be the case — but it’s not a particularly original insight. What fascinates me about “I Will” is the campaign’s neo-Foucauldian, or perhaps neo-Kafkaesque, executional cue: the inscriptions-upon-bodies that we can’t keep ourselves from reading.

In Discipline and Punish, among other works, Michel Foucault suggested that the modern State’s apparatuses of social control (e.g., asylums, hospitals, factories, and schools, whose “orthopedic” function is the correction, training, and taming of the individual subject) work in more or less the same way that pre-modern apparatuses of social control (e.g., chastity belts, torture devices, and branding irons) did. In each instance, the progressive effect of the apparatus is to make itself redundant — “ultimately one should be able to remove the apparatus and its effect will be definitively inscribed in the body.”

Foucauldians love to use that phrase — “inscribed in/upon the body” — don’t they? I wonder how many of them realize that Foucault was referencing Jeremiah 31:33: “After those days… I will put my law in [the Israelites’] bowels, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people.” A law inscribed in the bowels, in the heart, or otherwise upon the body is one that has become internalized, naturalized, normalized. It cannot be questioned.

Foucault was influenced, one has to imagine, by Kafka’s 1914 story “In the Penal Colony,” which describes a torture/execution apparatus that carves the sentence of the condemned prisoner on his skin before killing him, a practice considered humane and enlightened by the colony’s Officer, a priestly figure. The sentence to be inscribed upon the body of a character called the Condemned, a disobedient soldier, is “Honor Thy Superiors” — which certainly sounds proto-Foucauldian. Foucault was a genius; but Kafka, whose story actualizes God’s promise, transposes it from metaphor to fact, was a greater genius.

Unlike Foucault, whose theorizing merely condemns the orthopedic apparatuses that require us to internalize authoritarian laws and norms, Kafka also condemns the Explorer, an (apparently) truly enlightened European whose refusal to approve of the inscription apparatus causes the Officer to set the Condemned free and take his place. The Explorer programs the apparatus to inscribe an apparently anti-authoritarian sentence into the Officer’s flesh: “Be Just.” Exactly how, the reader wants to know, is this any better? Whether authoritarian or philosophical, religious or enlightened, words carved into the flesh (literally or figuratively) maim and destroy us (literally or figuratively).

Chevron’s phrases — “I will leave the car at home more” and “I will finally get a programmable thermostat” — are updated versions of Kafka’s “Be Just.” It’s not that I disagree with the sentiment; we should, indeed, use less energy. But when carved into our faces, by an enlightened energy company, words can hurt more than sticks and stones.

MORE SEMIOSIS at HILOBROW: Towards a Cultural Codex | CODE-X series | DOUBLE EXPOSURE Series | CECI EST UNE PIPE series | Star Wars Semiotics | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | Show Me the Molecule | Science Fantasy | Inscribed Upon the Body | The Abductive Method | Enter the Samurai | Semionauts at Work | Roland Barthes | Gilles Deleuze | Félix Guattari | Jacques Lacan | Mikhail Bakhtin | Umberto Eco