Modernist Cuisine

By:

September 30, 2010

I’ve been wandering slack-jawed through the pages of the web site for Modernist Cuisine, Nathan Myhrvold’s six-volume, 2,400-page gastronomic omnium gatherum. Publication of the book has been pushed back to Spring 2011 (for a variety of reasons, from the challenges of proofreading and color-correcting such a large work to delays in drop-testing the special double-walled packaging in which Amazon and other retailers will ship the complete set). Written with co-author chefs Chris Young and Maxime Bilet, the work can be fairly said to chart the polymathic Myhrvold’s obsession with the science, technology, and craft of cookery. The photography, including spectacularly-produced, artisanally-photoshopped cross-section images (featuring woks, gas ranges, Weber grills, and a host of other gadgets, all sawed in half with industrial cutters by Myhrvold et al.), is reproduced in rich, four-color stochastic printing.

As the title indicates, the inspiration and focus of the work is modernist cuisine, a movement that could be described as “cookfuturist” (pace @tcarmody) in its melding of state-of-the-art engineering and technology with a high regard for culinary craft. But Myhrvold’s goals are broader than an exposition of his parochial, if singularly-expressed, devotion to modernist techniques. The work aims to explain the phenomena of food with scientific precision, historical depth, and no small amount of flair. It’s eye-popping and even unnerving in its combination of relentless focus, quirky detail, and scholarly breadth.

My interest, of course, lies not so much with the cookery, but with the book. For it is a book, and only — emphatically — a book; no electronic version is planned (although Myhrvold doesn’t rule out a future edition). As Myhrvold explains, the Kindle had not shipped when work on the book began, and e-book technology has been in flux throughout its production. Furthermore, it was felt that no reading machine (iPad included) could do justice to the large, richly-saturated color images that are the book’s hallmark. Former Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft, Myhrvold presents the choice of the codex not as bibliophillic revanchism, but as a purely practical means of presenting his material in the best possible form.

And yet as a book, this sumptuous work has a swan-song feel to it. Like last year’s publication of Jung’s Red Book, or Phaidon’s phenomenally expensive Moonfire (bound with real moon rocks!), it’s a publishing project that seems intent upon ritually wringing every last drop of signification from the medium of print. Commentators are uniformly nonplussed at the book’s staggering size and cost — although it’s worth pointing out that for a work of this size and production expense, it’s quite fairly priced at $625 retail, or $500 when pre-ordered from Amazon or Barnes & Noble. Large, complicated works of scholarship frequently reach such pricing levels; the Oxford Companion to the Book, for instance, in a fat two-volume set, lists at $325 (for which I wrote entries for Harvard College Library and Widener Library, by the way, although I didn’t get to saw any libraries in half); and the Oxford English Dictionary will set you back just under one thousand dollars (without a single stochastically-printed picture in twenty volumes).

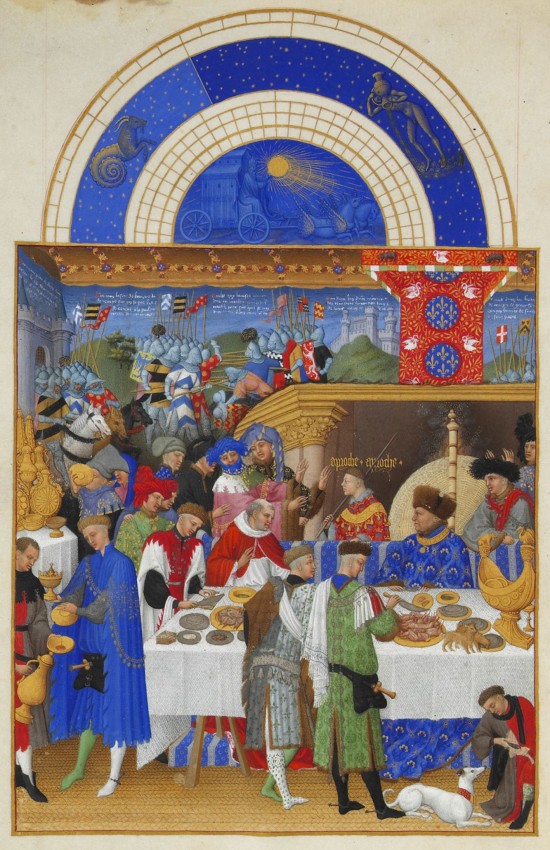

Unlike those big, multi-generational scholarly projects, Modernist Cuisine is essentially a vanity work–a spectacular, brilliantly-produced vanity work, but a work of vanity nonetheless. Myhrvold and the master craftspeople in his service have poured an overflowing measure of passion, brilliance, and technique into an undeniably beautiful work. I’m reminded of the Très riches heures du Duc de Berry, the monumental manuscript book of hours created in the fifteenth century. With 416 pages, including more than one hundred major images and three hundred decorated intitials, it is arguably the great manuscript work of the waning middle ages. Commissioned by John, Duke of Berry, in 1410, it was not finished until 1489 — nearly forty years after the printing of the Gutenberg Bible.

Perhaps this will be the work of the book in the waning days of print: to serve as a platform for the sacrifice of spectacular vanity.

A version of this post originally appeared at library ad infinitum.