1825-33: Post-Romantics

By:

July 13, 2010

Editor’s note: This is one of the most popular posts, traffic-wise, ever published on HiLobrow. Click here to see a list of the Top 25 Most Popular posts (as of October 2012); and click here for an archive of all of HILOBROW’s most popular posts.

Men and women born from 1825-33 were in their teens and 20s in the Eighteen-Forties (1844-53; not to be confused with the 1840s), and in their 20s and 30s in the Eighteen-Fifties (1854-63). Let’s call them the Post-Romantic generation.

The influential pop demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe lumped this cohort together with their immediate juniors (whom I’ve dubbed the Original Decadents); they have claimed that anyone born between 1822 and 1842 is a member of the so-called Gilded Generation. As I’ve argued before, although it’s true that members of Strauss and Howe’s so-called Gilded Generation were in their prime during the Gilded Age, and although the two cohorts I’ve identified within Strauss and Howe’s so-called Gilded Generation do have more in common with one another than they do with men and women born before 1823-4 or after 1843-4, the differences between the 1825-33 and 1834-43 cohorts are important ones.

A close look at such hi-, lo-, no-, and hilobrow Post-Romantics as, e.g., Camille Pissarro, Wilhelm Dilthey, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edouard Manet, Emily Dickinson, Gustave Doré, Gustave Moreau, Henrik Ibsen, Johannes Brahms, John Everett Millais, Jules Verne, Leo Tolstoy, Lewis Carroll, and honorary Post-Romantic William Morris, indicates that the opposition between modernism and romanticism is a vulgar one. Like the Original Decadents, the Post-Romantics are a transitional generation trapped in a productive tension between the Romantic and Modern eras. However, it’s safe to say that while the Decadents are more modernist, the Post-Romantics are more romanticist.

A reminder of my 250-year generational periodization scheme:

1755-64: [Republican Generation] Perfectibilists

1765-74: [Republican, Compromise Generations] Original Romantics

1775-84: [Compromise Generation] Ironic Idealists

1785-94: [Compromise, Transcendental Generations] Original Prometheans

1795-1804: [Transcendental Generation] Monomaniacs

1805-14: [Transcendental Generation] Autotelics

1815-24: [Transcendental, Gilded Generations] Retrogressivists

1825-33: [Gilded Generation] Post-Romantics

1834-43: [Gilded Generation] Original Decadents

1844-53: [Progressive Generation] New Prometheans

1854-63: [Progressive, Missionary Generations] Plutonians

1864-73: [Missionary Generation] Anarcho-Symbolists

1874-83: [Missionary Generation] Psychonauts

1884-93: [Lost Generation] Modernists

1894-1903: [Lost, Greatest/GI Generations] Hardboileds

1904-13: [Greatest/GI Generation] Partisans

1914-23: [Greatest/GI Generation] New Gods

1924-33: [Silent Generation] Postmodernists

1934-43: [Silent Generation] Anti-Anti-Utopians

1944-53: [Boomers] Blank Generation

1954-63: [Boomers] OGXers

1964-73: [Generation X, Thirteenth Generation] Reconstructionists

1974-82: [Generations X, Y] Revivalists

1983-92: [Millennial Generation] Social Darwikians

1993-2002: [Millennials, Generation Z] TBA

LEARN MORE about this periodization scheme | READ ALL generational articles on HiLobrow.

The Post-Romantics were more skeptical, iconoclastic than Romantic-era generations, yet less cynical than Modern-era generations. They rejected those Christian and classical values that for so long had formed a code whereby art was able to bring forth meaning; yet they had a romantic penchant for the past — for medieval life and art, for myths and fairy tales and folk tales.

It has been argued that Emily Dickinson’s poetry grappled with the major pre-Modern epistemological shift that necessitates a faith in empirical procedures. Dickinson “reimagined Romanticism … neither battening on the irony of irony nor believing in unbelief,” according to Richard E. Brantley’s Experience and Faith: The Late-Romantic Imagination of Emily Dickinson. Her healthy skepticism and religious doubt destroyed neither her faith nor her knowledge; instead, her faith was enriched and her knowledge deepened by skepticism and doubt. Dickinson’s radical skepticism was “both tough and tender,” claims Brantley; she never fully slipped into the Modern or Postmodern fascination with undecidability. Though it was proto-Modernist, her poetry resists the urge to dwell in suspicion.

Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych is modernist insofar as the relationships among Ivan and his family members appear to be fragmented and disjointed; yet — romantically — there is a high level of emotional connection among Tolstoy’s characters that’s revealed by the novel’s end.

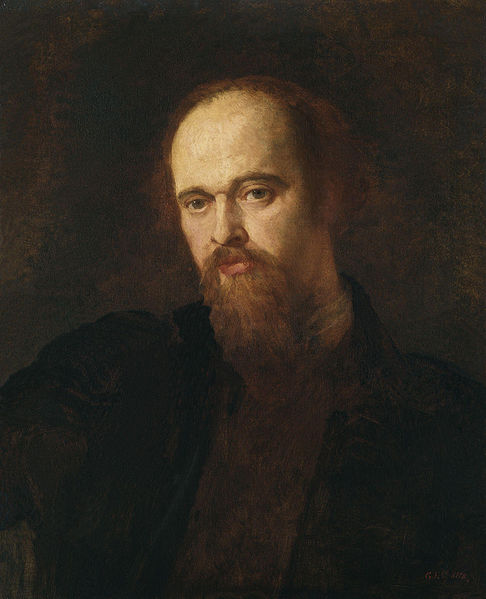

Consider the Pre-Raphaelites, whose supposed anti-modernism was a fundamentally modern movement in conception and ideology. The Pre-Raphaelites were a group of English painters, poets, and critics assembled in the late ’40s by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. They weren’t exactly modernist: because, e.g., they continued to accept both the concepts of history painting and of mimesis, or imitation of nature, as central to the purpose of art. However, some art historians consider the Pre-Raphaelites the first avant-garde art movement (i.e., instead of the Post-Impressionists) because they were reformists who rejected the mechanistic approach first adopted by the artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. Call them ambivalent modernists.

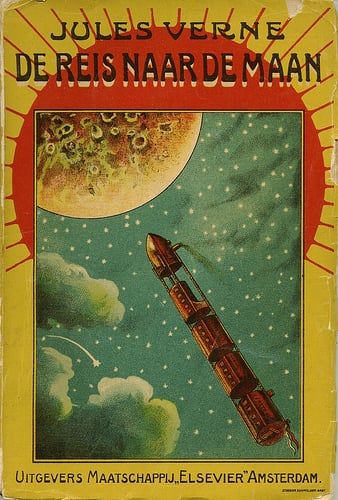

The Pre-Raphaelites believed (romantically) that medieval culture possessed a spiritual and creative integrity that had been lost in later eras. However, their backward glances were retrofuturistic — i.e., their vision is the inverse of [fellow Post-Romantic] Jules Verne’s, the supposed rationalist and promoter of science who (as Roland Barthes notes in Mythologies) was a conservative who looked to the future only in order to espy there the triumph of romanticist ideals in post-1848 France. Verne romanticized science and technology as fairy tales liberating his bourgeois readers from the tedium of modern urban life; the Pre-Raphaelites used romantic subjects taken from poetry and medieval legend as an excuse to present a proto-modernist, anti-bourgeois aesthetic of beauty for its own sake.

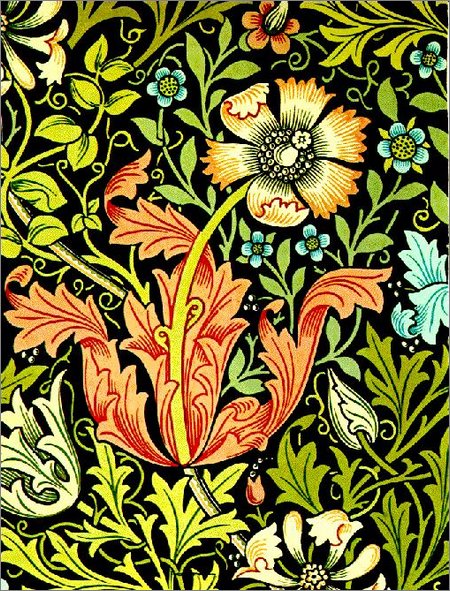

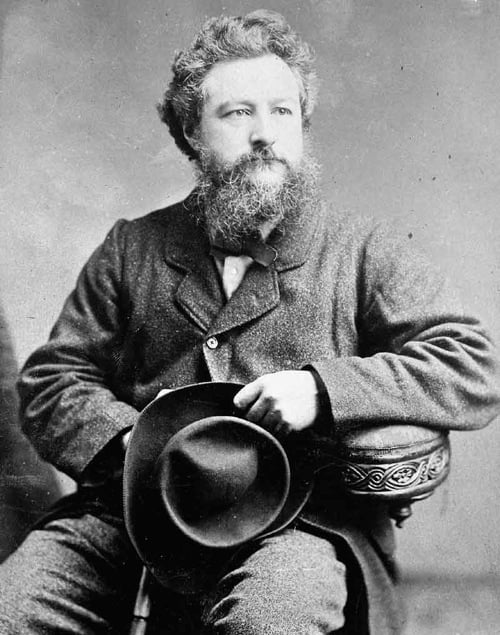

The writings of [honorary] Post-Romantic William Morris formed the basis for the arts and crafts movement. Morris advocated a romanticist return to well-made, handcrafted goods instead of mass-produced, poor quality machine-made items. Yet in his famous statement, “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” Morris outlined the modernist belief that utility was as important as beauty. Though a contemporary of the [Original Decadent] painter Burne-Jones, Morris fell under the influence of the Post-Romantic Rossetti while at Oxford — and helped Rossetti paint the new Oxford Union debating-hall with scenes from Le Morte d’Arthur; the three men would later cofound the decorative arts firm that became Morris & Co. Morris’ utopian novel News From Nowhere is the tale of a Victorian who wakes to find himself in the year 2102, at which time society has changed into a pastoral paradise, in which all people live in blissful equality and contentment. Like Verne’s novels, it’s a romanticist vision of the future.

NB: “Post-Romanticism” is a descriptor often applied to the music of Johannes Brahms (born 1833), who was simultaneously a traditionalist (in contrast to the opulence of his contemporaries, his music is rooted in the structures and compositional techniques — e.g., strict counterpoint — of the Baroque and Classical masters) and an innovator (his fondness for motivic saturation, i.e., keeping motifs and themes below the surface or playing with their identity, and for irregularities of rhythm and phrase, and his bold exploration of “enriched harmony” and remote tonal regions influenced modernists like Schoenberg and Webern). In the final analysis, Brahms was more romanticist than modernist; he even considered giving up composition when it seemed that other composers’ innovations in extended tonality would result in the rule of tonality being broken.

Worth noting that James Fenimore Cooper’s frontiersman novels become world famous from 1823 on.

Meet the Post-Romantics.

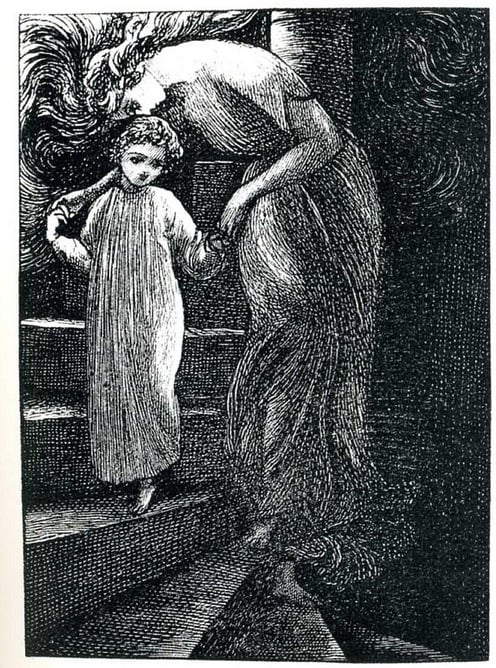

HONORARY POST-ROMANTICS (born 1824): George MacDonald (author, At the Back of the North Wind).

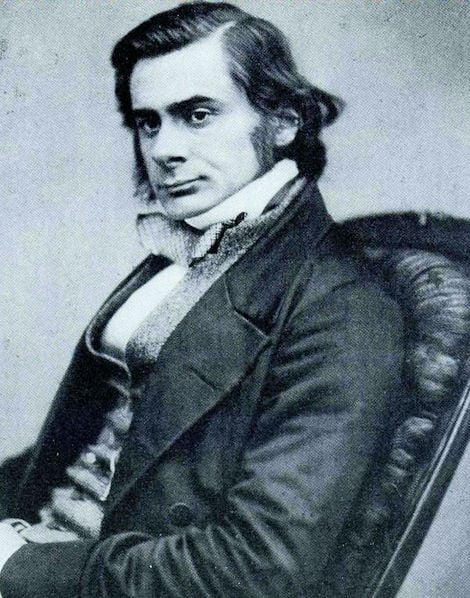

1825 (cusper): Thomas Henry Huxley (English biologist, known as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” grandfather of Aldous Huxley), Friedrich Bayer (founder of Bayer AG), George Phillips Bond (father of astrophotography), Jean-Martin Charcot (father of neurology), George Pickett (Confederate general, Battle of Gettysburg), Thomas B. Welch (grape juice magnate), Daniel B. Wesson (repeating pistol), Harriet E. Wilson (novelist, Our Nig), Robert Michael Ballantyne (Scottish novelist), Paul Kruger (Boer resistance leader). HONORARY RETROGRESSIVISTS: Johann Strauss (Austrian composer, The Blue Danube).

1826: Gustave Moreau (French painter), Stephen Collins Foster (preeminent American songwriter: “Oh! Susanna”, “Camptown Races”, “Old Folks at Home” (“Swanee River”), “Hard Times Come Again No More,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Black Joe,” “Beautiful Dreamer”), Matilda Joslyn Gage (pioneering feminist), Frederic Edwin Church (American painter, Hudson River School), Bernhard Riemann (German mathematician; made lasting contributions to analysis and differential geometry, some of them enabling the later development of general relativity), Hormuzd Rassam (Middle Eastern-born archaeologist, discovered Epic of Gilgamesh).

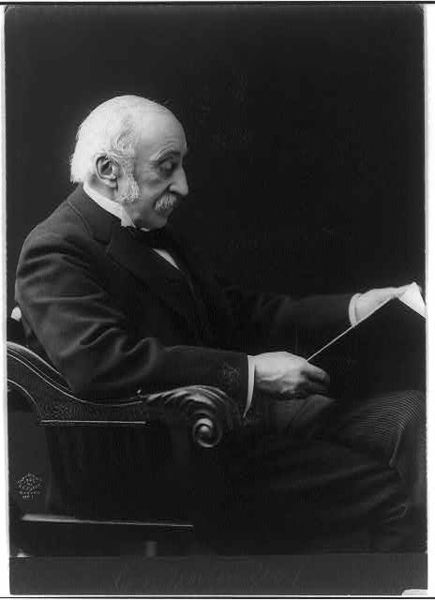

1827: Charles Eliot Norton (American man of letters, militant idealist, progressive social reformer, liberal activist), Lew Wallace (Civil War General, novelist: wrote Ben-Hur), Ellen G. White (American Christian pioneer whose ministry was instrumental in founding the Sabbatarian Adventist movement that led to the rise of the Seventh-day Adventist Church), Marcellin Berthelot (chemist), William Holman Hunt (British Pre-Raphaelite painter), Walter Deverell (British Pre-Raphaelite painter), Joseph Lister (English surgeon, pioneer of antiseptic surgery).

1828: Leo Tolstoy (Russian novelist), Henrik Ibsen (Norwegian playwright, Peer Gynt), Jules Verne (pioneering French science fiction author, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English pre-Raphaelite painter and poet), Henry Dunant (Swiss founder of the Red Cross), R. T. French (yellow mustard entrepreneur), Meyer Guggenheim (patriarch of Guggenheim fortune), George Meredith (novelist, The Egoist, Balfour Stewart (physicist who studied magnetism, radiant heat), Sir Joseph Wilson Swan (physicist — light bulb, photographic printing), Hippolyte Taine (influential historian)

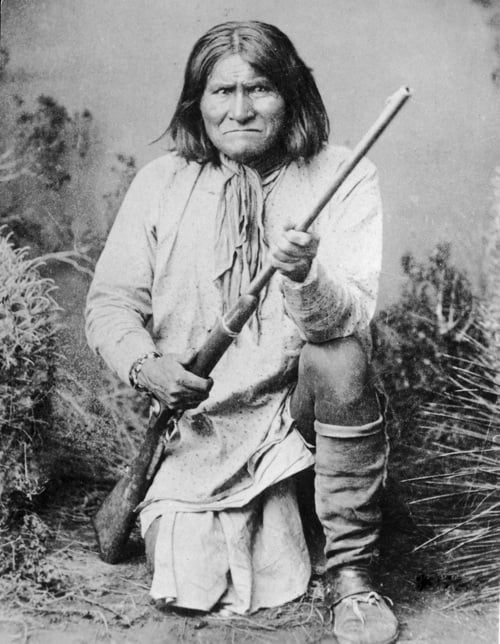

1829: Geronimo (Apache leader, the last Indian to surrender), John Everett Millais (British Pre-Raphaelite painter), Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys (Pre-Raphaelite British painter), Chester A. Arthur (21st US President), Asaph Hall (astronomer, discovered the moons of Mars), Levi Strauss (blue jeans businessman), Charles Dudley Warner (Harper’s editorialist), Catherine Booth (the Mother of The Salvation Army), Carl Schurz (German revolutionary and American statesman: “My country, right or wrong”), William Booth (founder of The Salvation Army), Shusaku Honinbo (Japanese Go player), Franz Reuleaux (mathematician, father of modern kinematics).

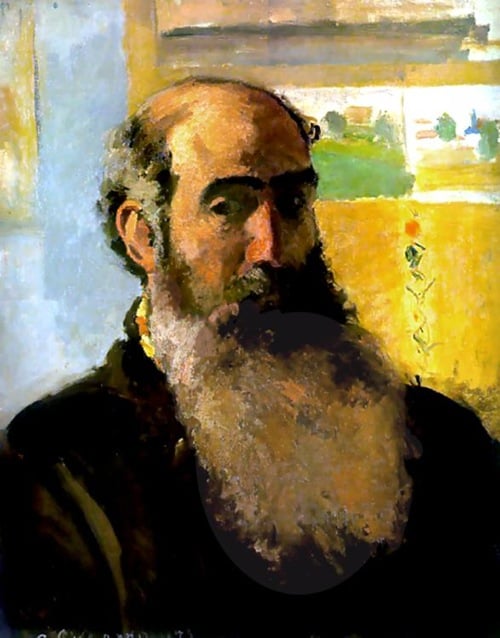

1830: Camille Pissarro (French Impressionist painter), Emily Dickinson (American poet), Christina Rossetti (poet), Eadweard Muybridge (photographer), Jules de Goncourt (French writer), Paul von Heyse (German writer, Nobel Prize laureate), John Batterson Stetson (hat maker), Emperor Franz Joseph I (of Austria), Belva Lockwood (feminist).

1831: Madame H. P. Blavatsky (founded Theosophy; author, The Secret Doctrine), James Garfield (20th US President), E. L. Godkin (co-Founder of The Nation), Sitting Bull (Warrior Chief of the Sioux), Arthur Hughes (British Pre-Raphaelite painter), Heinrich Anton de Bary (botanist, founder of modern mycology), Richard Dedekind (mathematician, developed theory of irrational numbers), Mary Mapes Dodge (American children’s writer and editor, Hans Brinker), Ignatius Donnelly (U.S. Congressman, pseudo-historian, amateur scientist: Atlantis, the Antediluvian World), James Clerk Maxwell (physicist, Maxwell’s equations), John S. Pemberton (inventor, creator of Coca-Cola), Philip Henry Sheridan (Union Army General), Peter Guthrie Tait (physicist, Treatise on Quaternions), Clement Studebaker (American automobile pioneer)

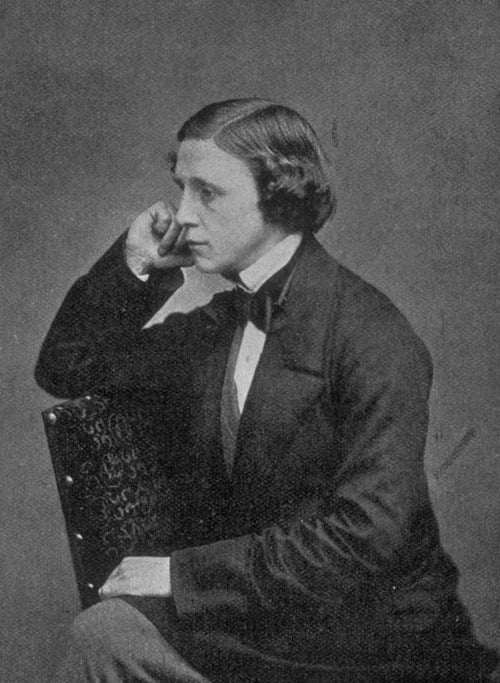

1832: Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, mathematician, author, Alice in Wonderland), Edouard Manet (French Realist/Impressionist painter), Louisa May Alcott (author, Little Women), Gustave Doré (engraver, book illustrator on steelplate), Horatio Alger (Unitarian minister, rags to riches author), Gustave Eiffel (architect, designer of Eiffel Tower), Maximilian (Emperor of Mexico), Nikolaus Otto (four-stroke internal-combustion engine), Edward Tylor (founder of cultural anthropology), Wilhelm Wundt (father of Experimental Psychology)

1833: Wilhelm Dilthey (German historian, psychologist, sociologist and hermeneutic philosopher; coined the phrase “the Hermeneutic circle,” influenced 20th century “Lebensphilosophie” and “Existenzphilosophie”), Johannes Brahms (German Post-Romantic composer), Benjamin Harrison (23rd President of the United States), Alfred Nobel (Swedish inventor of dynamite, creator of the Nobel Prize), Alexander Borodin, Russian composer), Charles Montgomery Barnes (founder of Barnes & Noble), Charles Bradlaugh (atheistic Iconoclast), Joseph Mortimer Granville (doctor, invented electric vibrator), Jeb Stuart (Confederate cavalry officer). HONORARY DECADENTS (born 1833): Edward Burne-Jones (British artist and designer, Aesthetic Movement); maybe Edouard Manet (French painter who bridged Realism and Impressionism; born 1832)

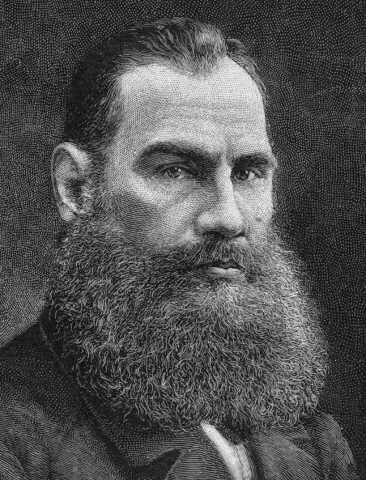

HONORARY POST-ROMANTICS (born 1834): William Morris (English poet and artist, Arts & Crafts movement; shown above), Carl Heinrich Bloch (Danish painter whose religious scenes are often used in Mormon literature), Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (French sculptor, designed Statue of Liberty)

NB: Somewhere in the early 19th century, according to patterns I’ve discovered via research and abductive methods, our decade/generation scheme shifts from a “5-4” to a “4-3” pattern. It seems fairly obvious that the shift happened in Paris, in 1830 — thanks to (a) the “battle of Hernani” waged by the Jeunes-France on behalf of romanticism vs. rules in poetry and proper language on the stage; (b) the July Revolution, which installed the “bourgeois king” Louis-Philippe and signaled the first triumph of the middle class in world affairs; (c) Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, which shattered the convention of “four-squareness” in melody, the rigidity of rhythms, and the predictability of harmonic formulas; and, finally, (d) at the Academy of Sciences, the break between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire over Lamarck’s hypothesis (which chimed with the Romanticist idea that everything is alive and in motion) about the transformation of species, i.e., Evolution. As a result, the the Eighteen-Twenties lasted only nine years: 1825-33.

Which means the Post-Romantics are a slightly smaller generation than every other one in my scheme. Those born in a 3 or 4 year after 1825 are cuspers; those born in a 4 or 5 year before 1833 are cuspers.

ADVENTURE WRITERS: Jules Verne (Top 200: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island, Michael Strogoff); Lewis Carroll (Top 200: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland).