Cocky the Fox (7)

By:

July 8, 2010

HILOBROW is proud to present the seventh installment of James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky the Fox, a serial tale in twenty fits, with illustrations by Kristin Parker.

The story so far: Cocky the fox, a handsome specimen of Vulpes vulpes living on the edge of an English town, is in trouble. His mentor Holiday Bob, top fox in the Borough, is dead. His family life has collapsed, and he’s moved in with his friend Champion, a distressed albino rabbit. His enemies are everywhere. And he’s been drinking a lot of aftershave.

Fit the Sixth saw Cocky and Champion on the move. Driven from Champion’s hutch by rats, ravens, general hostility, the dynamic fox-and-rabbit duo took off at low speed down the towpath of the old canal. Across the water lay the ungoverned zone, the gangster’s paradise, of the Northside — its proximity causing Cocky to reminisce about the time Holiday Bob brought a Northside boss low with a single, carefully deployed haiku. But even as he regaled us with the old tales, Cocky was losing his bearings in the moment. Arriving at Safeway Wood, trash-strewn demesne of Cocky’s pugnacious Aunt Patsy, our two friends seemed temporarily confounded. And Patsy was no help at all.

Cold autumn afternoon and we’re out in the gashed ploughlands. The woods simmer with rain, the fields hide their colours. It’s been like this since we left Patsy’s. Drooping light, poor drainage; everything sulks and seeps. Half a mile back I saw a weasel, asked him where I was, he just lifted his rain-maddened eyebrows and sighed.

‘Why are we stopped?’ says Champion. He’s been riding on my back and humming to himself as we go, a drone that dips and jolts as I navigate the lumpiness of the countryside. Which I hate — the lumpiness, I mean. Give me pavements, gravel, the bald municipal spaces! We’ve worked our way along a hedge-and-ditch arrangement between two fields, following the swell of the land towards high ground and trees. I’m sticking close to this hedgerow — hawthorn and stinking elder — taking no chances: we’re dreadfully exposed out here. Now we pause, a soaked two-headed animal at the edge of a landscape. Between my ears Champion’s breath is smoking like a censer.

‘I’m having a think,’ I tell him.

‘What are you thinking about?’

‘Mind your own beeswax.’

Here’s what I’m thinking about: I haven’t had a drink, other than slurps of puddle and rut-water, for days. Days! No aftershave, mouthwash, shampoo, paint thinner, floor soap, Red Bull, none of it. Trapped in the atmosphere of my aunt Patsy, sequestered in her rubbishy edge-of-town coppice, I endured a kind of withdrawal, perhaps. A little detox? Certainly I sweated and trembled, I felt reptilian. And yes, in my weakness I submitted to Patsy’s ruling fantasia, her ‘training program,’ whereby with the querulous dogmatism of the aged she had me doing slides and combat-rolls, jumping in and out of bushes, even attacking an old gym shoe: counterfeit savagery, flashing sad incisor in the gloom of Safeway Wood.

‘Less Cocky!’ she kept yelling. ‘More death!’

Champion looked on, from the rim of a cast-off tractor tyre, as I flounced in despair towards this target or that. He really seemed to be taking an interest. The ears were up, the nose working dispassionately: old scout, aficionado. ‘Enjoying this, are you?’ I said, rather bitter.

‘Dissolve!’ cried my aunt. ‘Abnegate! Depersonalise!’

I did try. I tried for her, out of helpless fealty to something, the past, tradition, the lays of the Borough, I don’t frigging know. But there was more sweat and trembling, more of that reptile feeling, web-footed and scaly, rolling deep glints in the murk.

‘Enough!’ I panted at last.

‘Not yet,’ said Patsy in her scratchy madam’s voice. ‘Not nearly. We’re looking for the killer in you, nephew. The arse-chewer, the eater of hearts.’

‘The eater of hearts?’

‘Metaphorically. You will consume the courage of your enemies. Chewing arses, though — that’s literal.’

‘I’m thirsty.’

‘Look at me… Your eyes should be lamps of death, casting the cold light by which death sees her way. But your eyes are all full of bullshit and too much sugar.’

‘You old carcass. I could fuck you up in five seconds.’

‘While you’re here, you’ll train, junior. Now hop to it. Another crack at that shoe. Go!’

‘Wait — where’s Champion?’

We looked around, Patsy not too bothered, me taut-jawed and swivelling my radar ears. Champion gone? A swat of panic. But there he was! Fifty yards away, splodged whitely against the dismal underwood, having hobbled off — so it seemed — in a pocket of rabbity curiosity.

‘Look at that,’ I said. ‘Two days ago you couldn’t get him out of his hutch.’

Patsy coughed, spat. ‘Well, another ten feet and his troubles are over.’

‘Eh?’

‘Those alders. That’s Rogie-town over there.’

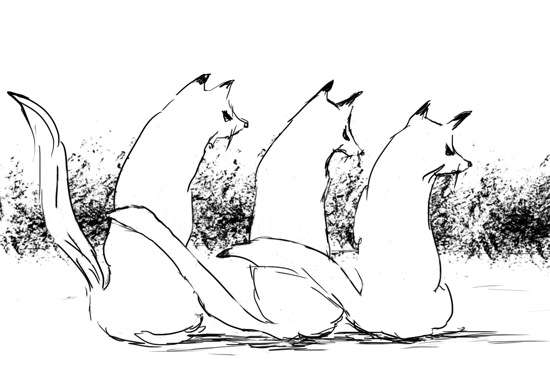

I was by Champion’s side in a trice. And none too soon! From the patch of tree-gloom indicated by Patsy three foxes were watching him. Big foxes too, wide heads and thick conker-coloured fur. Strong Rogie vibe: the stare of stupefied aggression, the dense rustic consanguinity, as if they were all each other’s uncles.

Some back-up would have been nice, even from my wobbly old aunt: Rogies are a tough fight, always — their pain threshold is out there. But I could hear Patsy far behind me, grumbling and scabbing around in her camp. I squared up anyway, tremolo in the legs, eye-sting. Lamps of death, eh? I could do it.

‘Ready for a taste of the streets, lads?’ They didn’t move. ‘Well come on, you fucking bumpkins!’

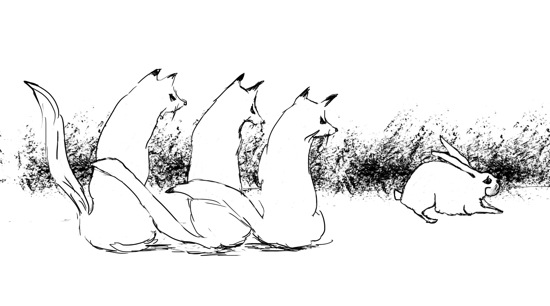

The Champ shuffled forward, sniffing diagnostically.

‘You with him?’ asked the biggest fox, country-gruff.

‘Er, he’s with me.’

He consulted with his colleagues. Murmurs, frowns, rumbles of assent. Then: ‘You,’ he said, ‘there’s a number of parties we could hand you over to, do quite well for ourselves.’ The other two foxes nodded. ‘Food and drink for a week, if we show up with you. But that one? That one we don’t touch. So. On you go.’

‘You what?’

‘Pass on, scandal.’

Well well. I looked back, for Patsy. The old vixen was in her own world, dragging with muttered curses a plastic bucket towards a mattress, arranging fresh configurations of knackeredness, intent it appeared on setting up some kind of obstacle course for me, her pupil.

‘Listen,’ I said to the Rogie chief, stance relaxed, fox-to-fox now. ‘How about you stop bothering her, too? You know? A bit of peace in her seniority. She hasn’t got long.’

The look on his face was: Don’t push it, sunshine. Telepathically, however, he acquiesced. I think.

And still the Champ advanced, making his lo-speed break for the edge of the wood. Ahead were the fields, with their heavy clay, and the magnetic roar of the horizon. ‘Pssst,’ I whispered, trotting alongside. ‘Where are we going?’

‘Badger-time, Cocky.’ He was out of breath.

‘Rumpy, you mean?’

‘We need [huff!] friends. Big strong friends.’

‘Yeah but what about the whole Northside thing? The hired lumps, like Patsy said? Pop over Twat’s Bridge, we could hook ourselves up with some serious goonage.’ (Pronouncing it à la française, straight from the salons of the Borough.)

‘Later,’ said Champion. ‘First [huff!] we find the badger.’

Sourceless light above the fields, water-shine in the sky. Open land, no feature or form. Could I dance out there, against the suction of the grave? Cocky must dance. How solemn were the Rogies, watching us go!

‘You’re the boss,’ I said.

And on we went.

Champion’s stopped humming, and his ungroomed yellow claws are biting into my shoulders.

‘Everything OK, partner?’

‘Ravens are watching,’ he says carefully.

‘Shite!’ I jink inwards, towards the ditch, where being top-heavy with albino rabbit I lose my balance and down we both go, arse over tip, scrabbling at the bank (me at least — I see Champion sliding by with eerie resignation) and coming to rest haunches-deep in freezing brown water, facing each other. ‘Where are they? In front? Behind?’

‘Ravens are watching,’ repeats Champion with precision, as if he’s been rehearsing the line in his mind. The sky overhead is of course quite empty, and we’re in our own little autumnal slum down here. Drowned grass, mud edged with ice, the hawthorn above in evil coils. Dead stems brush our noses.

‘Well, good one,’ I say at last. ‘You’re keeping us on our toes.’

‘Hm,’ says Champion, apparently quite satisfied.

‘Did he put you down here too?’ says a small colourless voice behind me. I whirl around in a spray of ditch-water, ready to fight, but its only a thin trembling almost-negligible country fox, his scent cancelled by the wet leaves that are all over him.

‘Eh? Who are you?’

‘He told me not to come out until it was dark.’

‘Who did?’

‘The squirrel up in the wood. Did he put you down here too?’

‘Nobody put me down here! I fell down here! Which squirrel?’

He’s not listening. The glumness of the ditch-spirit has him possessed. ‘It’s to be expected, I suppose,’ he says, in melancholy recitation. ‘This is the first time I’ve been out of my den for two months — I haven’t been very well — and this is what happens. But it’s to be expected.’

‘What are you talking about? Who’s this squirrel?’ I’m half-inclined to duff him up, so disgraceful a spectacle of foxiness is he presenting.

‘The singing squirrel in the wood. He told me that I was disturbing the badger and that I was to stay here until it got dark. He told me the power of the badger would strike me down if I moved.’

‘A-HA! Hear that, Champ old pal? That sounds like some friends of ours.’ I slither up the bank and look around. ‘Where do they live?’

The ditch-fox, peering up with smudged gaze, nods his head toward the higher ground, which I now see is a wooded tumulus. ‘Up there,’ he says. ‘We call it the Barrow.’

‘The Barrow, eh? Alright then! Come on, Champster, out we get.’

‘Five minutes. I like the water.’

‘You’ll make yourself ill. Come on!’

He pouts, but I have no time for this, so I crash back into the ditch and yank him out by his scruff. ‘You should climb out and all,’ I say to the little fish-fox. ‘Dry off. For your health.’

‘But the power of the badger — ’

‘You let me worry about the badger.’

‘Um, OK.’ But makes no move. I sling Champion onto my neck, and we head for the Barrow.

The power of the badger. Too right, mate! I caught a casual backhand off the old Rumper once, the reason long forgotten, and let me tell you it was a trip. Pillowy half-thoughts and distant, tinnital birdsong: I was gone for hours. I saw how big animals would go against Rumpy, fully up for it, and then how at first contact they’d change, half-turn from him, sink into deep inscrutable funk. As soon as Rumpy was installed in our crew the various problems we were having in and around the Borough just melted away. Physical, of course, his presence, but it had the force of an idea. Why fight? Why object? The idea prevailed.

And somehow Holiday Bob made the badger love him. The Rumpy era was the peak of Bob’s organization, high times for us racketeers. They all lined up outside the Yard with their tributes, and Rumpy the badger would work the door. Massive, sparklingly groomed, a spiffy monster guarding an invisible velvet rope. His looks had strange effects: so glorious he appeared, in his grey and white livery, in his size, that a certain class of beast would feel obliged to have a pop at him. Drunk weasels, urchin foxes, Rogies and Ramble-Ons from the country, something about Rumpy just outraged them, demanded a response from them, this affronting spectacle of indomitability. Once, I swear, I saw a young dandy rat go up to him and, impossibly, trail a limp paw down Rumpy’s chest. ‘Pretty nice coat, man,’ wheezed the rat. ‘You wouldn’t want to me to FUCK IT UP, now would you?’ Amazing!

This Barrow of his is very Rumpy, very Ancient Britain — grimly isolate, with views all round, a hump of druidic copse on bone-grey earth between three fields. Bush-scrag, twig-tangle, rooks half-arsedly complaining in the upper branches. How will I greet him? With a sketchy grin and no treats. Crap. I know his mafioso palate — a packet of Jaffa Cakes would have served me well in this situation. ‘Scared! Scared!’ sing a pair of ignorant starlings, beating their way through the soaked mid-air, as I put Champion in the hedge and step warily into the shadow and mood of the wood: there’s two old yews conspiring darkly in the middle, over what must be the entrance to his stinky frigging hole. Ugh.

‘Er, Rumpy?’ I call. ‘Rump? It’s — ’ And then something comes shrieking at me out of the tree-wires, pure panic, something with a wingspan and a terrible cry and — mad bulbs for eyes? I somersault backwards in a windy sprawl of terror and then… Wait a second.

‘Popjoy?’

A great voice fills the treetops and the rooks scatter. ‘Away!’ it booms. ‘Break not his dreadful peace!’

‘Popjoy you little fucker! Come down from there!’

‘Flossy?’ I always hated it when he called me that.

‘Yeah! No! Let’s see you!’

And he lands in front of me on the matted wood-floor, weightless as an insect, a cigarette-end of a squirrel. He doesn’t look well — the whittled-down neck, the two bug eyes in the fragile housing of the skull… His front teeth are blunted, wobbly. He’s lost a lot of his coat. His tail is a spike of nude cartilage with hairs like dandelion fluff. He sees me giving him the once-over and grunts.

‘The eating’s not so good around here. Not like in the old days.’

‘Well that’s why I came. Sort of on that theme.’

‘Eh?’ He hops weakly towards me.

‘The old days. There’s some, ah, trouble in the Borough and I was gonna ask Rumpy if — ’

‘OH no,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘Oh no no no! No, Flossy! Never!’

‘But I haven’t even — ’

‘Break not the peace of the badger! His earth-slumber of a thousand years!’ He’s back in the treetops now, rattling dead branches.

‘You’ve gone potty, you have!’ I shout. ‘You’ve been out here too long, in your weirdo tree-houses! I want Rumpy, the tax-dodger’s terror! Rumpy, scourge of the slag! There’s beatings to be given! Grumpy Rumpy, come out! Emerge! RISE!’

Popjoy contemplates me from his nodding perch, splinters of white sky behind him. ‘Did you ever hear his poem?’ he asks.

‘What poem? Rumpy never wrote a poem.’

‘Oh but he did, my friend. A poem indeed. I may have helped him a little, supplied the odd word, but the feeling was all his. Listen.’ And in his wood-shaking Dylan Thomas voice, with eyes closed and extra drama, he begins to recite.

‘Slow moves the hour, and thick is my heart’s blood

With grumpiness, and sad rememberings…’

‘Rubbish!’ I shout, fretting in the briars.

‘Because they took my Holiday away

And left me here, at the back end of things.’

‘Back end? What is this, a drinking song?’

‘Life is nowhere, nothing now has fire…’

‘Cobblers!’

‘But only flickers in a mocking show…’

‘Balderdash!

‘Because they quenched my flaming Holiday

In waters that are black, and never flow.’

‘It’s… terrible. Stop, please.’ I can’t move — something’s come over me. Popjoy inhales gustily and booms out again:

‘At his command I let my rage expand

I hammered all our foes into a haze

And now I live alone in these cold woods

Til some avenging slag should end my days.

All those great battles, all the beasties bashed

When Holiday and I were stepping strong!

The gruntings and the glory! They have left me

Powerless to move this hour along.’

He concludes. He waits on the high branch. Half a field away the rooks cry in their orbit. And I say nothing.

There’s nothing I can say, because my heart, my fox’s heart of oil and gristle, is breaking.

Who taught these animals to write such wonderful verse?

Will the badger ever come out of his hole, which is of course his depression?

And what could account for the strange attitude of the Rogies toward Champion?

Find out in the next episode, on Thursday July 22.

SAME FOX-TIME!

SAME FOX-CHANNEL!

Read the seventh issue of The Sniffer, a COCKY THE FOX newsletter written and edited by HiLobrow’s Patrick Cates.

Our thanks to this project’s backers.

READ MORE ORIGINAL FICTION on HiLobrow.com.