Pop Arcana (4)

By:

June 30, 2010

Editor’s note: This is one of the most popular posts, traffic-wise, ever published on HiLobrow. Click here to see a list of the Top 25 Most Popular posts (as of October 2012); and click here for an archive of all of HILOBROW’s most popular posts.

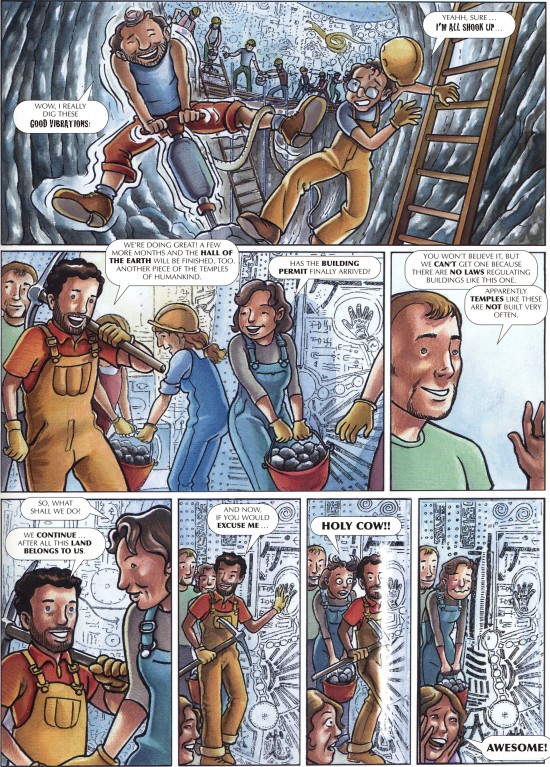

Over thirty years ago, a handful of initiates into a vibrant and esoteric Italian mystery school took up hand drills and picks and started to dig a hole into the side of a mountain in the foothills of the Alps. The property, an hour north of Turin in the Valchiusella valley, was called the Federation of Damanhur, and it is now one of the most complex, dynamic, and creative intentional communities on the planet. With over six hundred permanent residents, and hundreds more “citizens” of various grades scattered around Italy and the world, Damanhur possesses an enviable range of quality businesses, workshops, schools, healing centers, and quasi-independent collective homes, all organized according to an innovative governance system notable for its pragmatism and productivity. Damanhur organizes conferences, restores medieval buildings, sells high-end cloth and foodstuffs, and trades goods and services among themselves using their own currency. But the community’s on-the-ground success story pales in comparison to what that hole in a mountain became. Over the weeks and years, without much formal training, working at night and with music blaring to cover up the drills, a select crew of Damanhurians hollowed out a series of mighty chambers and passageways, all without other members of the community — to say nothing of the greater world — clueing-in to their secret work. With tenacious devotion and a startling degree of art, they transformed these underground spaces into the Temples of Humankind: a remarkable otherworldly honeycomb of sacred murals, onyx mosaics, stained glass, sculpture, inlaid marble, hidden passageways, precious metals, mirrored stone, alchemical elixirs, and — who knows?— maybe even the cosmic energy circuits, intergalactic portals, and temporal wormholes that the people of Damanhur suggest are the ultimate functions of their sacred architecture.

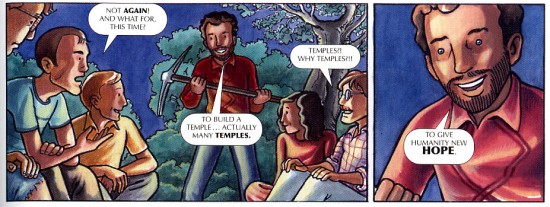

In 1993, the Italian authorities got wind of the Temples and, with encouragement from a grumpy Vatican, raided the property. Unable to find the entrance to the defiantly unofficial temples, they threatened to blow up the mountain. The founder of Damanhur, an enigmatic but appealing character named Oberto Airaudi (“Falco” within the community, whose members go by animal and plant names) had to make a choice. According to the story told in Checkmate to Time, a charming comic book sold in the Damanhur gift shop and available in English in The Traveler’s Guide to Damanhur (North Atlantic Press, 2009), Falco consulted with a council of cosmic powers. The council was divided, with some proclaiming the earth too hopeless a case to risk the revelation of sacred technology to the secular authorities. Falco then decided to open up the temples to the officials, who were suitably moved and astounded by what they saw, even as they remained unclear about their responsibilities. Four years later, after an intense PR campaign and a protracted legal battle, the Temples — which continue to be revised and expanded today — were formally protected, and are open to devoted visitors for the somewhat pricey fee of 60 Euro.

I was perfectly happy to fork over the money when I visited Damanhur last spring, however, because I am a spiritual tourist. It’s a tag I wear proudly, not because I am not also a traveler and a seeker, but because I like to do my traveling and my seeking with full knowledge (and enjoyment) that I am a tourist as well. Besides, serious seekers limit their pilgrimages in ways that the eclectic, omnivorous, and sometimes willfully perverse spiritual tourist does not. I have gotten as much out of tacky roadside shrines and UFO cults as the most charismatic buildings of the A-list faiths. It’s all about perspective. I willfully cut my sacred with profanation, and keep my eyes peeled for sparkling ironies as well as eruptions of the marvelous. Visionary experiences occasionally occur, though mostly when I haven’t been looking for them; in general I have found that attention, pleasure, and an open mind is all the reverence necessary to meet the powers that inhabit a place. Like all tourists, I am on the hunt for a thrill, but I know that a spiritual thrill, “genuine” or not, can be an initiation, a portal, a wake-up call.

My guide to the Temples of Humankind was Esperide Ananas, a former PR pro who serves as the Director of International Relations for the Federation of Damanhur — a snazzy title that makes up somewhat for the unfortunate translation of her Damanhurian name, which is Butterfly Pineapple. Given Damanhur’s debt to the visionary spiritual counterculture of the 1970s, Esperide was appropriately decked out in tight designer jeans, foxy pumps, a wide woven belt, and an Egyptian pendant the golden color of her big head of frizzy hair. Relaxed and funny, she proved a decidedly groovy Virgil as she led me through a parking lot to a nondescript door that led us to an elevator that delivered us finally into Damanhur’s labyrinth of astonishment.

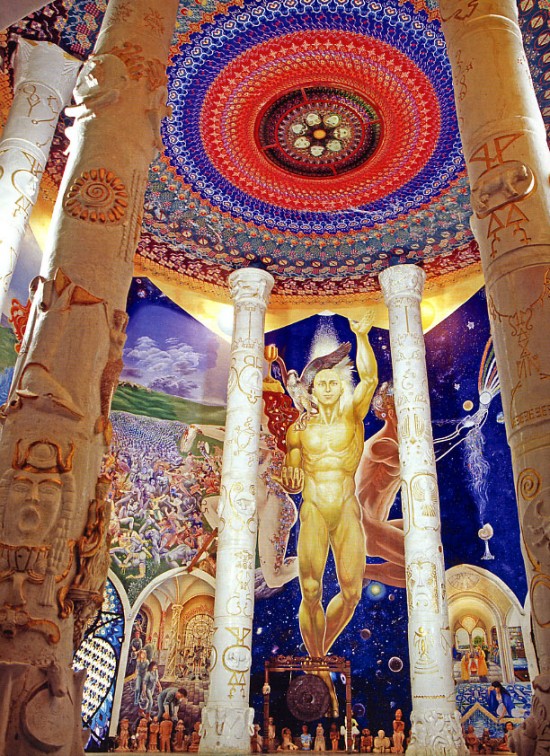

Before I visited the valley, I had checked out the lavishly illustrated Damanhur book put out by Alex Grey’s COSM Press (and written by Esperide) as well as the British seeker Jeff Merrifield’s sympathetic half-insider book of the same name. But these did not come close to preparing me for the scale, intensity, quality, and profound intentionality of the community’s templum mysticum, whose vibrant nexus of materials, forces, signs, images and uncanny implications makes Damanhur’s Temples the most colossal and transformative expression of modern visionary art that I have had the privilege to see. Even if you are allergic to the programmatic New Age homilies on some of the murals, the bravura, invention, and sheer craft of the Temples must be recognized as belonging to a major work of world art, at least in a popular or “outsider” vein. At the same time, part of the transformative power of the Temples is their reach beyond the categories of art and architecture, sacred or otherwise. The Temples are, in some fundamental sense, something else, utterly present manifestations of a process very much beyond our ordinary ken: an esoteric time machine perhaps, or an Epcot Center for visiting ETs, or a memory palace echoing with the pregnant footfalls of our once and future species. Whatever else they are doing, the Temples are making the visitor a subliminal or esoteric proposition, and however vague and outlandish these implications remain for the cagier spiritual tourist, there is, as the author Richard Grossinger writes, “no escaping the fact that everything in the temples is devoted to the faith that this proposition is real.”

My tour began, like some hermetic ladder planted in base matter, in a two-chambered hall deep in the mountain and dedicated to the Earth. Entering the lower chamber, I stepped onto a finely-crafted mosaic floor whose figures represented, as do many designs in the Temples, the stages in a human life; images of tourist cameras and space stations announced the temples’ refreshing refusal to banish the icons of contemporary society for the sake of a fantasized “timelessness.” The surrounding circular wall was covered with a single flowing landscape of trees, oceans, and mountains, along with bucolic collections of people and endangered animals. With the strident localism of all mural art, these images declared their objectivity, their presence. “We are not representations!” they cried. Esperide explained that the faces of the frolicking humans were based on the actual citizens of Damanhur, although a few heads remained unpainted in anticipation of future incomers. These portraits thus allowed citizens to leave a trace of themselves permanently inside the temples, which also contain hundreds of small clay doppelgangers created by initiates, gathered in cubbies and passageways like goofy Egyptian ushabti. Without making it explicit, this first chamber already suggested one of the esoteric functions of the Temples, which is to serve the community — and by extension humanity and the earth — as a kind of ark, a visionary vessel of saving memory.

As with many of the psychedelic paintings (and famous album covers) of Mati Klarwein, Damanhur’s figurative murals and images couple a clear illustrative surrealism with dreamlike juxtapositions and tricksy shifts of scale and perspective. Though often bordering on the kitsch, or at least the comic book, these images are also constantly framed and reframed by more abstract “cosmic” fluxes — some invisible, perhaps, and some figured by the alien glyphs, trompe l’oeil effects, exotic ornamentation, and psychedelic stained glass that pervade the temples, whose leaded patterns trace hidden glyphs. The central pillar in the lower chamber of the Temple of Earth, for example, is carved in false marble with two somewhat garish, metamorphosing human figures; but the crown of the column flares into a striking abstraction, a psychedelic pattern in glass that conjures a blue-print of etheric energies. Esperide tells me it represents the Big Bang.

The silent attendant who followed my friendly guide and me through the Temples then shut off the lights, and the ceiling of the chamber erupted into a simulated snapshot of the heavens as they looked from southern Europe 22,000 years ago. Apparently that date had something to do with the first awakening of humanity, but that esoteric dollop was not half as interesting to me as the way the artificial night-sky reflected on the dark green polished marble below, so that for a moment I felt like I was walking through stars. As I left the chamber and climbed up the eight steps leading to the rest of the hall, I realized that together the floors of the two halls formed a cocked infinity symbol, spilling upwards and forwards, another echoes of the Temples’ fundamentally temporal concern with change and return.

The second Earth chamber, bright with golds and reds and more aggressively esoteric and fantastic imagery, was a masculine retort to the previous room’s maternal blue waters and green woods. Energetically, the mural was dominated by a bald Blakean man floating against the void, with a falcon on his shoulder, a possible reference to Falco but also a symbol of the cosmic form of Horus that, along with Pan and Bastet, is the community’s most important godform (and not its only echo of Aleister Crowley’s Book of the Law). Esperide told me that a blast of black light would reveal a female figure traced over this fellow, transforming the figure into the primal androgyne, or Adam Kadmon, so key to the currents of Western hermeticism that Damanhur both channels and significantly transforms.

These sorts of echoes and overlays saturate the Temples, which become a literal palimpsest, dense with traces and “hypertext” links: to earlier designs, to the surrounding rock, to alchemical lore, to sacred languages, and to visions and spectral orthographies snatched from dream and trance. In this idiom, abstraction has power, like the planetary sigils of occultism or the yantras of Asian tantra. One grim and brooding giant to the right of the cosmic androgyne is cloaked with enigmatic tracery that, Esperide informs me, prevents the dark energy of the figure from escaping. He embodies the “anti-life” principle the Damanhurians call the “Enemy of Mankind”; Esperide explains that he represents limitation and decay as well as the ignorance that cloaks our sacred origins, with the result that we forget that we are not humans so much as “divinity having a human experience.” Unlike many of today’s New Age religions, which serve up a gooey custard of “all is one” non-dualism, Damanhurian cosmology acknowledges an evil or satanic force within reality. But rather than breeding paranoia and violence, this cosmic and psychological foe helps to inspire the community’s extraordinary commitment to practical labor and collective self-creation. On the wall facing the Enemy we see a sort of apocalyptic battle, only the combatants — whose faces once again are based on the citizens of Damanhur — are fighting their own restricted and limited selves. And they are smiling as they do it.

Part of the magic of the Temples, you realize, is that their very existence strives to confirm the reality of Damanhur’s esoteric sources of inspiration. How else could they have pulled off this immensely inspired and difficult task? you wonder. And I have barely scratched the surface in my account. I haven’t told you about the Hall of Metals, with its dense invocation of the elements and the ages of man; or the classy Hall of Spheres, with its rich red marble and globes of alchemical concoctions; or the labyrinth, with its extraordinary iconic wikipedia of stained-glass godforms from Africa, Sumer, Scandinavia, Japan, Greece. Other than the elevators, everything in these caverns and tunnels was created by the community itself — few of whom, the story goes, were trained in the arts, crafts, and engineering roles they were called upon to play. Though there are instruction maps of transformation everywhere you turn, the Temples are ultimately less about message than sheer manifestation — the expression of a workaholic DIY pragmatism that, you sense, wants to pervade and divinize the whole world of matter, not to transcend it but to awaken it. Earlier in the day, a woman I met named Magpie Goldenrod had insisted that the Damanhurian way was “not a religion but a philosophy, one that gives meaning to what we are doing with our hands.”

What — or who — could inspire such production? I did not get to meet Falco, who has a gentle face in photographs and, like many of today’s CEOs, often wears a baseball cap. Like everyone else these days, Falco seems to understand the danger that lies in expressing the classic form of the charismatic sectarian leader. So for all the supernatural claims made about him — community lore mentions his early feats of levitation —Falco has creatively modified his inspiration role in a sustainable, “postmodern,” even entrepreneurial fashion; he possesses what the Italian sociologist of religion Massimo Introvigne calls “non-charismatic charisma.” Though some of the usual anti-cult complaints are hurled Damanhur’s way, and there are certainly apostates, the community has remained untainted by the usual demagogic scandals for over thirty years. And while Falco’s non-ordinary claims still guide the community, Damanhur’s politics, social dynamics, and esoteric physics (major terms include chaos, synchronicity, and arrows of complexity) all possess an unusually evolutionary and experimental edge, and so lack the dogmatic authoritarianism that so often results in glassy-eyed sheep. Though Falco is very much the visionary leader, his vision is more like a piece of avant-garde theater than a divine blueprint. While there are plenty of details of this lore in Merrifield’s book, the most appropriate source remains Esperide’s comic book, which exploits the fantastic dimension of the genre to confound history and the supernatural the same way that it blends the simple clean line of the cartoon with actual photographs of the temple.

In addition to being seen as a sectarian leader — with all the dangers that implies —Falco also must be recognized as an incredibly ambitious visionary artist, an architect of esoteric Happenings and a crafter — on both spiritual and entrepreneurial levels — of what James Carse calls “infinite games,” the “game” being one of Falco’s major terms for social design. And he is, indeed, an artist — a gallery in the former Olivetti headquarters that the community took over contains dozens of his colorful, densely coded, and wildly titled abstractions. An alchemical blend of Paul Klee, Basquiat, and LeRoy Neiman, these canvases — with their handsome prices and hallucinatory 3D effects produced under dancing lights — are displayed alongside quotations from Wittgenstein and Duchamp (“The observer creates the work”). Within the Temples, the Water Temple, also known as the library, is a principle creation of Falco, who covered its dome-shaped surface with a menagerie of otherworldly graffiti, cosmic diagrams, inter-dimensional formulas, and alien languages (twelve of them, to be exact). For the community, these lingos represent information of incredible complexity, much of which is only understood by Falco himself. Fans of outsider art or, frankly, the art of the insane, will also recognize the peculiar power of arcane data-dense graphology, with its horror vacui and unknowable implications.

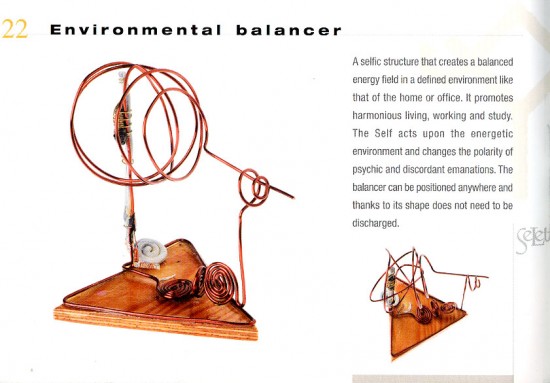

But again, art alone cannot account for the palpable sense of power humming in this chamber, which is topped by a beautiful blue cupola of stained glass. Citizens — and pregnant women in particular — come here to pray, not just for the proximity to all these galactic downloads but for the hidden channels of water coursing behind the walls. More important are the fluxes of the “synchronic lines” that are supposed to meet in the rock of this chamber — four immensely powerful ley lines of earth energy, represented by four golden serpents, whose conjunction in this mountainside was what apparently drew Falco to this property in the first place. Such invisible forces are not just passively received in the Temples, but are actively generated and transformed through the literally hundreds of tons of copper wire whose dense and intricate coilings and couplings with other precious metals surrounds the corridors and chambers of the Temples. Damanhurians refer to this mostly camouflaged energetic circuitry as “selfic,” another esoteric remix of those swirling and seemingly intelligent energies — chi, od, radionic vibrations, Mesmer’s fluidum, Reich’s orgone — that rightfully beguile alternative healers and rightfully irritate hard-nosed empiricists. In particular, selfic circuits derive from the alchemical and informational potentials of metals — potentials that are only coarsely manifested in our existing electronic circuits and memory chips. Besides turning the temples into a colossal spectral radio antenna, selfic technology is also applied on a smaller scale for a host of quotidian purposes — sleep, travel safety, relief of menstrual cramps. In the gift shop I dropped twenty-five Euroclams on a nifty coin-sized spiral that promised to improve my memory. (I keep forgetting to carry it around with me, though.)

These are the sorts of claims, of course, that gall today’s militant and imperialist materialists, who worry about quackery and the further erosion of rationality’s cheerless command. But take a tip from a seasoned spiritual tourist: we needlessly narrow the world of possibilities (of our experience as well as reality) when we force the entirety of such sectarian experiments through the meat grinder of reason. The spiritual tourist does not drink the Kool Aid; but she inhales its intoxicating aroma. Faced with a selfic contraption, I recognize my lack of unwavering belief in its efficacy (though I no more understand the placebo effect than you do). At the same time, I do not turn to the court of reason for some final verdict of thumbs up or thumbs down; instead, I surf the excluded middle into the wilderness of virtual possibilities opened up by the more ambiguous reality engines of art and game. For me a selfic gizmo is an esoteric assemblage — a term that consciously invokes Deleuze and Guattari, Castañeda’s “assemblage point,” and the material practices of the avant-garde. After all, many of the most vital and revolutionary artists of the last century and a half were batshit with esoterica. And even when such undomesticated notions and energetic practices create those more dangerous social formations some call “sects” or “cults,” such games must still be compared in their overall effects to the other games that so many people play today — games like, I dunno, hopeless despair, or terminal gadget addiction, or corporate toolery, or the navel-gazing retreat into narcissism that characterizes much contemporary “spirituality.”

But what if the Temples as a whole are an esoteric assemblage? What forces are they mobilizing? Here things get really space opera. Before entering the temple, over lunch at the nucleo (collective household) that Esperide calls home, I had asked her about what made Damanhur unique in the array of the world’s esoteric and spiritual paths. She said it was their take on time, and particularly their sense of time as a kind of dimension or territory. To demonstrate, she held up a paper napkin, which she then, as the conversation turned — as it so often does these days — to the grim state of the world, ripped in half. “But time has a tear in it. We are on the edge of that tear, and there is not a clear way to move into the future. The fabric is frayed.” In some sense, she said, our future has already happened, and it is not pretty.

The citizens of Damanhur believe there is more than one strand of this frayed weave. What Damanhur wants to do with its Temples and its vital community experiment is to remember a different future, to materialize a more distant time-line and to thereby rewrite our current course in a more positive direction. In less SciFi terms, they are mobilizing a theater of possibility. By embracing futurity as a positive field of action while reinvigorating the small-scale self-sufficiency of the past, Damanhur wants to show that, as Esperide says, “humanity can be different, that we can have a different relationship with the planet.” The symbol of Damanhur, scattered everywhere throughout the environs of the community, is the dandelion, a charming but thorough vector of dissemination.

Spiritual tourism is partly about seduction, about the unexpected call one feels toward unknown gods, or invisible forces, or to other modes of being and perceiving. As a contemporary expression of the visionary imagination, the Temples were, for me, nearly unparalleled. But they only really got me off when I closed my eyes. The final stage of my tour was the imposing Hall of Mirrors, whose large polished trapezoidal surfaces are designed to mirror you back to yourself. I was taking in the hall’s remarkable glass cupola when Esperide took up a mallet and went over to a gong in the corner beneath a sculpted bird and hammered out crescendo whose insane peak went on far longer than sonic decorum would ordinarily permit. My eyes were closed, and the moment bent and shattered into a kaleidoscope of time-stretched events: deep terran drones, enveloping spectral reverberations, and high-frequency shimmers that seemed to signal from somewhere far far away, over the rainbow.

Pop Arcana is a limited-run series of columns written for HiLobrow by Erik Davis.