Time Capsules

By:

June 8, 2010

For reasons that are trivial here, I find myself basking in the yellow pixellation of a mercury-vapor streetlamp on a cold night in mid-November. What skein of events, what arrangement of acts and things led me to this moment? The catalogue of causes is endless and banal: boredom with cello and the chess-prodigy circuit; ruin of college and serial gaming obsessions; pressure of graduate school, dwindling prospects of success … the keening of flocks of returning geese as they hurtle through the darkness overhead mingles with a fresh-conjured headache to make me wistful and retrospective. But this kind of thinking has become all but incomprehensible to me now. It’s simpler to focus on the physiology: a drop in cystolic dopamine levels in synaptic clefts, the surging reuptake of serotonin permitting withdrawal’s early tidal seepage, a trickle of psychic acid already ravaging holes in my levees. So here I stand beneath a ceiling of goose-honk waiting for a car to turn the corner and fleetingly toggle its headlights, at which signal I’ll slip into the curbside shadows to commit a violation of Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act.

But as the car makes its wonted turn, a rustle from behind raises my nape-hairs. I wheel and confront a hectic silhouette, epaulets and porkpie hat.

“D’ye know me Simon Moyes?” he asks in a too-loud voice.

“Why no, I…”

The awaited car speeds up, gliding away to my left. I watch it recede, then turn to the interloper.

“I’m sure we’ve never met. If you’ll excuse me…”

“These are yours,” he says, and thrusts a bag at my face.

Bewildered, I take the bag and walk away at a furious pace without looking back. This isn’t the way it usually happens. But I’m curious — and I’m sweating, and my brain is trying to throb its way free. So I open the jar, shake one of the strangely heavy pills into my palm. I lick, registering some shock as the pad of my tongue goes utterly numb at the pressure of the pill. Not tingly-numb — void-numb. And then I swallow, the same curious sensation following the pills’ passage down my trachea and through my abdomen, like some dark searchlight revealing caverns in my body, splintering abysses.

And then that sensation explodes.

I am hunched, looking down and forward, and I feel myself begin to stretch out ahead. The world peels away from a me that is not me, a me now absenting itself by degrees in some shimmering granularity, the what-am-I-now caterpillaring through unblinking moments as I fall back and back, a back which is also a down — and everything goes away from me, the shadowed trees, the road in all its particles, all of it now extruding at every point as a taffy-rope of time wide as the world dangles me, bobs me backwards, holds me skidding in place while the stream rushes on. And then the whole of self settles back into self, back into a moment which endures and dies like all the others ever have, and something like a sense of now restores itself by degrees through all my corpuscles.

I’m back in the pool of piss-light, where I stand tremoring. A car peels around the corner. A cool blade of saliva lies against my chin. The car’s headlights flicker familiarly. And then a rustle behind me stirs my nape.

Comes the voice again: “D’ye know me Simon Moyes?” Croaking, exhortatory, like an Ahab of indolence.

I turn as I had before, but now I only gape dumbly. Staggering away, into the light and out of it again, I slip in dry gravel. At the crunch of road-matter I notice that the geese are gone — their honk silenced, their low-hurtling palpability now an absence in the sky. And the fellow in the porkpie and the epaulets still stands at the edge of the light; I make my way up the gentle hill back to the bus stop and as I turn the corner I look back down the street and still he’s there.

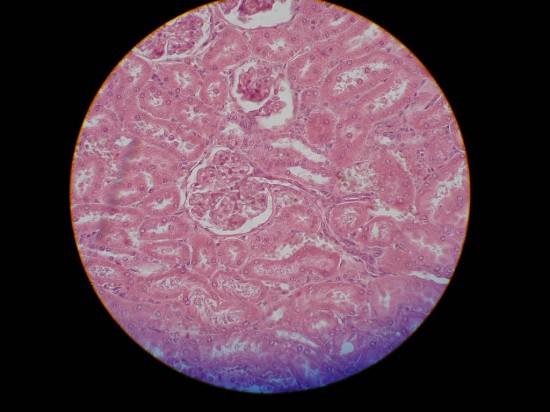

I feel as if I’ve climbed out of a pit of déjà vu — a flash of recurrence that registers not in the forebrain, but behind the heart, in kidneys and knees, down to the tingling jointures of toe and nail. An estranged exhilaration overtakes me, an uncanny renewal, as if standing at the window of some grim teller I had just redeemed a fistful of misspent moments.

At home I tear the unmarked glass jar out of the bag and shake out a few capsules, which jiggle to rest on the scuffed countertop. One rolls under the door of the microwave, whose clock with its blinking dots reminds me of the lateness of the hour: a quarter to midnight. The moon has risen to fill a pane of the kitchen window with its liquid brilliance. Retrieving the pill from the nook and holding it up in the light, I take note for the first time of its mottled translucence, a milky cloudiness like the atmosphere of some unknown planet. Or our own planet; the whorls figure white and pale blue. But here an unexpected something I notice — it moves. Whatever compound the capsules contain is swirling, motile, a flickering cloudscape in fisheye miniature.

These are not the sort of pills to which I am accustomed. In fact I’ve never used anything like them. By some obscure action they accomplished a reset of my withdrawal, which I had not even noticed until I stepped off the bus and walked to my building. Only now am I beginning to feel the need edging its way into the scene again, clouding my cup of consciousness. But of the business with the return of the fellow with hat and coat, and the rehearsal of our script of a minute before, I can only wonder.

Refreshed by curiosity, I pop the pill into my mouth. Like the first, this one takes its numbing, abyssal course; again there is the soul-dangling sensation of the world leaving me behind. But having anticipated it I find it voluptuous, empowering, lightening. It takes its course out of time; I know not how long I stand there shivering in the flux. But suddenly — with no leaking let-down, but a sudden phase shift —I’m here again, feeling my pulse in my palms as I press them to the counter. And then I notice the microwave clock beating its lucent tattoo, only with a difference: it now reads 11:44.

I’ve learned to trust anything but the fickle essay of my senses upon the world. And so, I pop another pill: the delicious absence, the dangle in the gyre. And when I come to a rest again, the clock reads 11:43. I pop five more; the house flings apart and reassembles itself five minutes earlier. Tears are puddling in my eyes, spidering the digits: 11:38. But for their crimson glow the room is utterly black; the moon is gone. Perhaps it is behind a cloud, waiting to reappear at 11:44? Aside from this unexpected change, I feel completely well. Beyond a fleeting dizziness there is no discernible down — no cotton-mouth thirst, no headache, no hunger.

The next day I take the train into town. Often I go there to watch the chess-players in the square — rarely to play; the game’s heights long ago proved to giddy for me. My game-playing propensities find their outlet now online. To be sure, I never play the shambling prince of the plaza: the fellow in the straw hat whose little sign, depending from the table, pronounces him the “Chess Master,” who entertains tourists with feats of ludic legerdemain. (candidly, I will admit that I played him once while my postgraduate career was in steep decline. But I couldn’t unseat the old liar, who sits there still in his incongruity like a polo player with a tattoo.)

Today I stroll and sit at intervals, wondering what to do with the time capsules. Of course I could use them to get rich, or at least to engage in some significant larceny: watch the lottery announcement while standing in a convenience store, then pop a pill, pick the numbers, and cash in. I could save them for emergencies — in case of injury or the onset of illness. I could use them to make a hero of myself, backing up to just before the emergent moment to thwart the cause: to pull the child back from path of the oncoming truck, to turn trip the hold-up man before he begins his assault. It’s an easy route to the kind of attention I crave — which means, of course, that it’s only a criminal enterprise of another kind.

But what if the pills aren’t the “time capsules” I think they are? It could easily be a delusion, the effect of a heretofore unknown but perfectly normative province of the pharmacopeia. But if they act as I believe they do — if they grant a small reversal of time, even the mere minute I’ve observed — what if the attendant cycling of probability produces a different set of numbers? What if time itself is a series of lottery-tumbles, each moment instantiating a possibility plucked from the random flux? It can’t be: things have causes, effects, event opens onto event. Time isn’t a set of die-rolls — instead it must be unfolding causation, topless towers of Chinese boxes, fractal suggestions, some algorithm compounding the next from the state of the now. But even if it’s so, maybe randomness opens up a window on the unlimitedly stochastic — maybe there’s freedom in the swerve. I don’t know. And now I realize that I’m becoming paranoid with respect to the functioning of time itself.

Unsettled, I flow with the crowds of jobbers crossing the streets of the square at the lights. Drawn by force of habit, I find myself back at chess tables in the plaza by the cafe. And it occurs to me that here’s a test to consider.

It occurs to me now what a great advantage the capsules could give me. The sixty-four squares, the thirty-two pieces, the two players — even with its millions of moves, the game offers a system in which these retranches of time might be modulated and controlled.

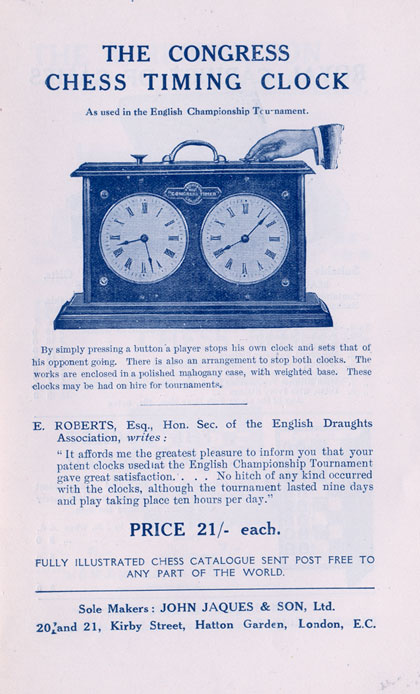

I watch the chess master dispense with a few comers before I take my chance. He beckons; I settle into the concrete dish of the chair, feeling the play across my face of the shadows of ash trees toiling in the breeze. The chess master is setting the black pieces in place when he peers up from beneath the weave of his straw hat. “Five minutes,” he croaks, fiddling with two-faced chess clock at the edge of the board. His rheumy eyes swivel to glimmer up at me, pale balls of lightning caught in a well. I set the pieces in place on the terrazzo tabletop; the chess master still eyes me through the haze. I look down, move my queen’s knight’s pawn forward a single square and swipe the clock.

The chess master mirrors my move. He asks my name, and I tell him. Four moves follow in quick succession as we castle our respective kings. And then I realize an error: developing my king’s bishop, I carry the move too far down the diagonal, leaving my position exposed. The bottle of pills is resting in my right hand; now I twist it open and pop one into my mouth.

And as I make this swift movement, and just before I tumble out of time, the chess master breaks into a smile.

I fix on the clock dials spinning back in the rattling aurora. When the world settles again, the board is set up before my mistaken move. I shift the bishop again, shortening by three squares the distance traveled. But soon enough I’m in trouble once more. This time I draw the bottle to the tabletop. Placing it on the board with a quiet clack, I dip out a capsule and hold its swirling iridescence up for the chess master’s inspection.

“You’ve seen these before?”

Again, the smile, the reptile gleam in the orbits, as he draws from his vest pocket a grimy rubber coin purse, pinches open its mouth, takes out an identical pill.

We swallow simultaneously, and the battle is on. He comes out of the drop quicker than I do every time, making his moves as swiftly, grinning like a coyote battened on innocence. We’re careening through time move by move, the chess clock teetering on the brink of five minutes. How much time passes for us I do not know, but I am learning the game’s deeper twists and turns swiftly as we navigate the all-but-endless iterations. It’s like I’m falling out of the sky into a hole in the earth: a familiar topography of gambits and defenses gives way to layers of estranged possibility. The figures of the lurkers and the chess-watchers shuttle in and out of the haze as our material conditions flutter and change: one moment we’re shifting our pieces in the midst of a hail storm, then we find ourselves sitting in alone in a vast field of torn plastic, fires decorating the horizon. But in the precinct of the table nothing changes — our attire remains the same, the grit and stains of the chessboard keep their shapes and textures, even the ash tree still sways overhead.

And still we’re only tearing at the late edges of the opening gambit. Looking into the bottle with a capsule poised at my lips, I notice that their number is greatly reduced. It took much longer than I expected to consume this many pills; it’s as if they’ve been replenishing themselves. But now their number is dwindling.

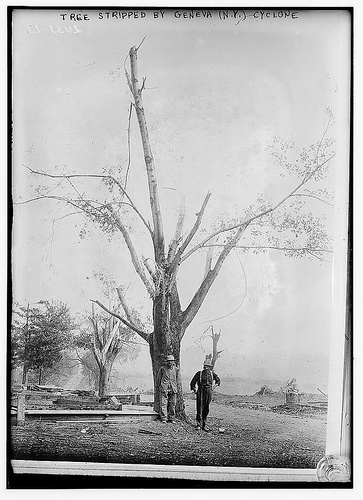

“Look around,” the chess master suddenly croaks. “It’s getting gray.”

Surveying the square, I notice how the light fails at a certain circumference, that beyond the limit of the plaza with its trees, all is cloudy absence.

“Maybe you ought to walk around a little, see what you can see.”

I move away, noticing now how my knees creak as I stand. My body is tired, dessicated, crumbling. I walk away until the chess master and the trees recede in a pool of dim light. And then I return.

“Well, what’s out there?” he asks.

“Nothing. Beyond the edge of sight there is nothing, nothing at all.”

“Nothing, then?” he replies. “It’s been going that way a long time now.”

And suddenly it’s clear. My first pill shut out the geese, locked their migration out of my time-bounded world. My binge in the kitchen cost me the moon. By some terrible relativity, gaining a moment of time causes the annihilation of some volume of space. Freedom in the swerve? I thought that’s what the pills were about. But there is none of it, not for us addicts. Although my every urge would defy it, this is a universe in which nothing can be gained without cost. The existential economy may seem vast: order and entropy, matter and energy, space and time. But for all those abstractions, it’s quite simple. And time is especially costly in our world, is it not?

It has grown chilly in this — this what, this move, this instantiation, this world… however I define our narrowing space, it has grown chilly, and a breeze still toils in the boughs of the ash tree. The chess master shivers. Reaching down to the great bag at his feet, he draws out a soiled trench coat by the epaulets.

I’m staggered with the recognition. “You,” I say. “You’re the one who came to me. You gave me the pills.”

“Did I?” he replied, settling the coat about his shoulders. “Maybe I did. I remember a time, ages ago seems like, when I wanted to bolt from this place — this time, if you take my meaning. I thought of trying to sell the pills. Some version of me must’ve done it then, back in that other time.”

“But why?” I ask.

“I can’t say for sure,” he replies. “Probably I figured you’d be the one to take my place. But I’ve lost track of that. Fork in the road came up, and I took it — took another pill, fought my way out of yet another game. But it only led to other games, and others, and others. And now I’ve lost track of the paths,” he concludes, settling back in his seat. “As have you, I might add. I know that playing this way — taking the pills, drifting in the streams of time —I became ‘the Chess Master.’ Biding my time, so to speak, taking a pill whenever I made a bad move. I learned my way around the maze of the game, eventually, and only needed to take the pills once in awhile. Until you came along.”

I sit astonished. “But at what price?” I stammer. “For in this time — and all the ones left to us, I’d bet — we’re marooned, cut off.”

At this the chess master only shrugs, holds up the capsule still caught in his fingertips, and regards me questioningly. “I dunno,” he says. “But let’s play on, what do you say?”

I look at game clock. the hand on my dial continues to move; I’ve nearly used up my limit of time. “Not yet,” I say.

“Good for you,” he replies. “Me, I’ve been doing this too long. Now I just want to go away — and when the pills run out, I wager, my time will be all spent up. But maybe you can take comfort in this: in one of the worlds we spawned, you are now the chess master. In another, storms of fire and sand and, who knows, maybe shredded plastic, have blown us both to bits. In one we’re famous; in another we got dragged off to jail. And somewhere in there, you stepped away from the game early enough to find your way back.” And with that, the chess master takes his pill. There is a momentary blur about his figure, too brief for casual notice. And there he sits still, pill tipped to lips.

I’m weeping. “I’m glad we took the time to talk about it, anyway,” I say to the only other person I know. And looking now at the board, I see a move. It leads to check, but not to mate. I make the move, swipe the clock, swallow the pill. And once more the world falls away — now languidly, casually, fittingly — as it will again and again in a recession of timeworlds ever more intimate.

There’s more original fiction on HiLobrow; there are more hilo-tales by Matthew Battles, too.