Fake Authenticity

By:

June 1, 2010

This article was first published in Hermenaut #15 (1999). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

We have a hunger for something like authenticity, but are easily satisfied by an ersatz facsimile. — Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (1990). *

The quest for authenticity is an ugly thing. Will there never be an end to the spectacle of (usually white, middle-class) people draping themselves in exotic tribal fabrics, bribing sherpas to haul them up mountains, spending $15 for turkey-burgers in urban hunting lodges, throwing out perfectly good kitchen tables for expensive new tables made out of old barn doors, and fetishizing people darker and/or poorer than themselves? All of the above, and more, can be summed up under one phrase: fake authenticity.

Coined by Hermenaut’s hard-working Critical Affairs Department, fake authenticity is that which is false, in the sense of counterfeited. Need an adjective to describe bars and restaurants with ethnic, historical, or outdoorsy themes; or new items of clothing or furniture that have been distressed, weathered, stone-washed, and otherwise pre-aged for the purpose of looking like it’s been used or worn, for years, by someone who works on a farm/with his or her hands; or urban hipsters who adopt or otherwise admire what they imagine to be the non-white (or ethnic white), urban/rural (i.e. non-suburban), working class, and “outsider”-in-general style of life; or anything and everything re-enacted, “authentically reproduced,” and Disneyfied in general? Try: fake-authentic.

It’s important, however, to distinguish between the fake (which can mean “insufficiently authentic,” but which usually just means fake) and the fake-authentic. Returning to the language of our Camp/Kitsch issue [#11/12], whereas the fake is simply kitsch, which can be transformed by the lovingly ironic person into camp, the fake-authentic is cheese. Let’s use, as an example, one of those restaurants which try too hard to seem Italian — by hanging overly sentimental postcards of Rome all over the place, or something. This may not be your idea of authentic — shouldn’t the theme to The Godfather be playing in here? — but so what? As writer Al (Thrift SCORE!) Hoff asks: Is the food good, or not? The insufficiently Italian restaurant is harmless kitsch, and it likely offers beautifully weird rewards to anyone with eyes to see them [see my “Interview with Daniel Clowes,” this issue]. There is nothing you or I can do about the bad taste of people who can’t distinguish between fake and authentic, people who wear imitation leather jackets and “Kiss Me I’m Irish” T-shirts like they mean it… but again, so what? Which is really worse: honestly enjoying the whitebread stylings of Pat Boone, or just pretending to enjoy cheesy Cocktail Nation send-ups of whitebread? [Note that not all Cocktail Nation-era musical acts are cheesy; Combustible Edison isn’t.] Irony, the engaged kind of irony which does not preclude real emotion, nor even seriousness, is still possible in a world of fakeness; but in a world where fake authenticity has triumphed, nothing remains but sincerity on the one hand, and a glib, mocking version of irony — cheese — on the other.

Sentimentality is one of the problems, sure, but only if we can’t replace it with real emotion. The Olive Garden, for instance, which is one of these places where you’re “treated like family” and the portions are too enormous to be believed, is not the answer to Italian-restaurant kitsch. It’s worse: It replaces the (cheap, degraded) emotion of the ersatz facsimile with the cold calculation of the simulacrum, the replica which has replaced that which it was only supposed to replicate. The fake, as Baudrillard has said for years, is charming; the simulacrum is not.

This is why cities like Los Angeles and Las Vegas no longer seem as awful to us, today, as they did to progressive types forty years ago. A culture of fakeness has inoculated these places against fake authenticity (though not for much longer, surely). But here in Boston, fake authenticity has long since won the day. Through a process which America’s favorite columnist Slotcar Hatebath (misappropriating the term from the museum world) calls authentication, everything here in the Hub of the Universe which was actually old has been made Olde instead; historical façades and interiors have been restored not to how they used to look, but to how (city planners imagine) tourists want them to look; every incident of (family-friendly) historical importance which has ever transpired within city limits is now re-enacted in an entirely Disneyfied manner.

Even the 19th century brewery building (now owned by the company which invented Samuel Adams beer, itself an excellent example of fake authenticity) in which this publication is headquartered trembles on the verge of authentication. No doubt we will soon be forced out, to make way for fake-authenticity-seeking suburbanites who want “artist condos” in an historical building where someone else’s ancestors once roasted hops. (Luckily, we have a money-making scheme in the works. All I can say right now is: Pre-Off-Roaded SUVs. Beaten with chains and tumbled around in a gigantic clothes dryer. Beep me, babe, I’ll fedex you the prospectus.) Boston is not a “museum,” as hipness-deprived college students, transplanted New Yorkers, and ex-suburbanites complain — because museums are supposed to preserve the past. Instead, this city has become a simulacrum of itself, a gift shop(pe) writ large.

This is not to say that there is something authentic about Boston, i.e., something which must be allowed to speak for itself as opposed to through the interpretations of historians. But, as Clarke Cooper notes in “Debasement by Acclaim” [this issue], it’s one thing for an individual (a historian, here) to express his or her unique and inspired vision of reality, but it’s another thing for the culture, whose place and ability it is to generate the consensus that makes communication among us possible, to try to do the same thing. An historian’s interpretation of Boston is a work of artifice and imagination, it’s a fake — but this does not preclude it from being an authentic representation of the city. But when that sphere of society whose role it is to enforce inherited forms and norms gets into the action, the result is always an example of fake authenticity.

A note, here, about Disneyland. There was something attractively naïve about that amusement park’s recently-demolished Tomorrowland exhibit, because although Disney’s Wernher von Braun- and science fiction-inspired world of monorails, rocket ships, and homo sapiens extra-terrestrialis began as a fake-authentic vision of the future, the passage of time has revealed it to be nothing more noxious than a fake. Tomorrowland has been replaced, however, by a more “realistic” vision of the future, one in which rich executives (whoops, I mean “we”) won’t get to wear anti-gravity shoes, but in which we will instead telecommute from bucolic farmhouses and fly-fishing streams. Fake authenticity, in this example, is so little removed from life that it makes reality itself inauthentic. Which is part of the problem.

No authentic human life is possible without irony — Kierkegaard, The Concept of Irony (1840)

Although Italians do open restaurants, there is no such thing as an authentic Italian restaurant. Although history, nature, race, and class are very real and very much with us, there is no such thing as an authentic past, an authentic outdoors, nor an authentic non-white/middle-class style of life. News flash: Poor urban blacks do exist when they’re not being featured on America’s Funniest Race Riots, but there is no item of clothing, no compact disc, and no affected manner of walking or talking which will allow anyone who is not poor, urban, or black to approximate that. “Authenticity” is a reality-label from the art world, and as such it cannot be fixed to anything living and vital. There is such a thing as authenticity — keep reading — but whenever authenticity is evoked, these days, we are in the world of fake authenticity.

Art, as we all know, is “something everyone can do.” What everybody cannot do, however, is brilliantly express a singular vision of reality. Art made by the kind of artist who can do this is often derided — particularly when he or she works without sufficient resources, or in a despised medium (e.g., science fiction, comics) — by audiences brainwashed by the smooth, shining surfaces of capitalist realism, as fake. But, as I’ve said, fakeness isn’t a bad thing. In fact, as long as we include fakeness within our definition, we can still apply the term authenticity profitably to all manner of phenomena — because not only is the fake often as authentic as that which it imitates, it can be more so. It’s possible for young Japanese rock musicians inspired by the Cramps, or even the soundtrack to Grease, to play a wildly twisted version of rockabilly with passion and originality. How is this not authentic rockabilly? That it’s in no way authentic in a manner which the world of fake authenticity would recognize is a plus, not a minus.

At the risk of sounding foolish (because the terms have been enormously devalued in recent years), it’s important to talk about art and creativity here — because all great thinkers on the subject of existential authenticity use the artist as their paradigmatic example. Breaking with the Platonic/scientific tradition of supposedly discovering pre-existing meaning, objective reality, transcendent values, and the true self, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, and Camus — to name only those philosophers discussed in In Search of Authenticity (1995), Jacob Golomb’s history of existential authenticity — choose to make these things themselves. When the 22-year-old Kierkegaard wrote, in 1835, “The thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live or die,” this was no exercise prescribed by The Artist’s Way. Instead of looking inward, hacking his way romantically through the underbrush of convention and habit to the source of his self, he was creative; he artistically engaged with a social world he found constraining and immoral. When Nietzsche wrote that the world is composed not of questions with answers, but of “infinite interpretations,” this was not a resigned statement of relativistic nihilism, but a challenge to each of us: to boldly interpret where no one has interpreted before.

Before being an artist, however, the would-be anti-hero (anti-, because whereas a hero perfectly embodies society’s prevailing ethos, the person seeking existential authenticity rejects every ethos in favor of his or her own subjective pathos) of this type of authenticity must become an ironist. By irony I in no way mean to refer to that hip, sarcastic glibness which passes for irony at the moment, and which is nothing but the flip side of a hip earnestness which, being in no way less glib, is even more outrageous. Kierkegaard, a master ironist, warned against an overly corrosive irony in his essay The Concept of Irony, noting that Socrates was “overwhelmed by irony; he became dizzy, and everything lost its reality.” So precisely because our kind of ironist is someone — and here I use Richard Rorty’s definition, from Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989) — who faces up to the historical contingency of his or her own most central beliefs and desires, and recognizes that these beliefs and desires don’t refer back to anything transcendent (beyond the reach of time and chance), he or she is also someone who’d never buy into that cynical legitimization of the status quo which today goes by the name of irony.

To the anti-hero of authenticity, Golomb suggests, irony — which facilitates the emergence of authenticity by helping us become detached from those things we take for granted — is paradoxically “the voice of commitment and caring, the optimistic call to innovation and formation, rebirth and transformation.” Like empathy, creative interpretation only becomes possible when we’ve de-centered ourselves, and learned to see (and hear) the world with new eyes (and ears). An ironic appreciation of the fake can help, here. In Sincerity and Authenticity (1971), Lionel Trilling describes an irony of simultaneous commitment and detachment, a “patrician posture” which he says “cannot fail to outrage the egalitarian hedonism of the educated middle classes.” That’s the kind of irony I’m talking about. The sincere do-gooder and the earnest moralist judge everyone by received criteria of behavior, criteria which are what Rorty calls “inherited contingencies.” It is up to the (anti-)heroically insincere person (in Wilde’s terminology) to judge without being judgmental, and to behave morally without being moralistic.

It doesn’t matter what the jargon [of authenticity] says, so long as it is spoken in a voice that resonates properly. — T.W. Adorno, The Jargon of Authenticity (1964)

Existential authenticity, then, could be defined as something like “that mode of existence in which one becomes ironically and radically suspicious of all received forms and norms, and in which one strives to lucidly affirm and creatively live the tension of human reality in all its contingency, ambiguity, and absurdity.” Fake authenticity, in this context, means something like “an overly subjective, anti-bourgeois rebelliousness in which the cause of social and political revolution is furthered by wearing pre-frayed Dockers, driving a luxury version of a rancher’s utility vehicle, and maintaining a sarcastically vague and noncommittal suspicion of bourgeois society.” This mode of fake authenticity is all around us, every day, typically expressed in what Theodor Adorno called “the jargon of authenticity”: a nonsense-language that seems to express (in a resonant voice) a need for meaning and liberation, but which only serves to mystify and oppress.

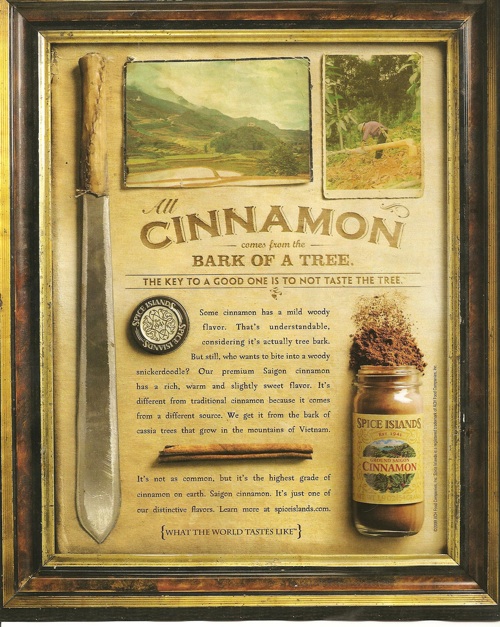

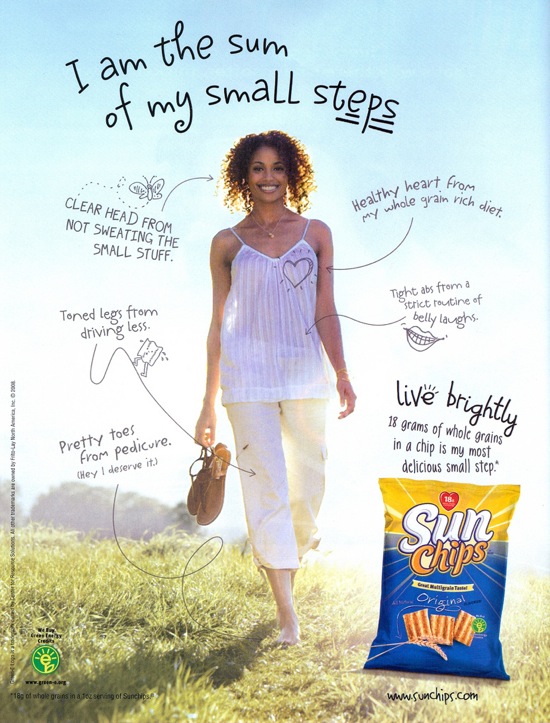

Thirty-five years ago, Adorno argued that the jargon of authenticity is closely allied with the manipulations of advertising. Sure enough, as the twentieth century nears its end, the idea that one can rebel against bourgeois life by buying what Thomas Frank, the editor of The Baffler, has described as “soaps that liberate us, soda pops that are emblems of individualism, and counter-hegemonic hamburgers,” is all-triumphant. We can see what the Baffler calls the “commodification of dissent” present in the pre-history of existential authenticity; perhaps by understanding the origins of both authenticity and fake authenticity we can finally get a handle on why (as opposed to how) the commodification of dissent has been so successful.

The pre-history of existential authenticity begins two hundred years ago, according to philosopher Charles Taylor’s The Ethics of Authenticity (1991), as the bastard child of German philosopher J.G. von Herder’s ur-Romantic notion that each of us is called upon to live our lives in an original manner, and to realize a potentiality that is properly our own, and of Rousseau’s articulation of the idea that the freedom to do whatever we want, without external restraint, is not enough-that we are only truly free once we’ve liberated ourselves from internal constraints, and decided for ourselves what’s important. Rousseau is still very much with us, of course, in New Age ideology and all manner of progressive politics; and Herder lives on in the cult of individuality which atomizes communities and sells oceans of radical soda pop. The pseudo-radical cult of authenticity which bothered Adorno so much in post-war Germany (and which thrives today in the form of goateed para-boarding schwags who imagine there’s something inherently rebellious about extreme sports) began here. Decades before the slogan “Just Do It” was burned into our brains, Adorno noted that “Authentic Ones” like Heidegger were given to making gestures of autonomy without content, serving only to help advertising celebrate the empty meaningfulness of immediate experience. But this still doesn’t quite explain the commodification of dissent. There’s a missing piece, somewhere.

Taking Adorno’s cue, we can work our way upstream to Heidegger, the existentialist thinker who made the term authenticity popular in the first place, and whose many real achievements as a philosopher of authenticity are almost negated by his proto-schwag propensity for dressing like a Swabian peasant and living in a ski hut all year round. True, Heidegger betrayed authenticity’s ironist position by making a cult of rusticity, by demonizing cosmopolitan (Jewish) intellectuals, and by insisting that the philosopher’s true place is in the field with the farmer. (“One would like at least to know the farmer’s opinion about that,” muses Adorno.) It’s true, as Adorno notes, that Heidegger was in this sense an anti-intellectual intellectual, obsessed not with helping people become more suspicious of received truths and values, but instead with rediscovering their true “roots.” But again, although this does help explain much of today’s fake authenticity, it’s not enough. How is that authenticity developed into the “jargon of authenticity”? How did it become possible for radical ideas (encounter, commitment, and conviction, at one time — today even our jargon, whose most often-chanted mantra is a flaccid choice, is debased!) to be “squirted like grease into the same machinery it once wanted to assail,” as Adorno put it, while the oppression and atomization of those without power continues apace? How did the truly rebellious ideal of authenticity come to “accommodate itself to the world through a ritual of non-accommodation”?

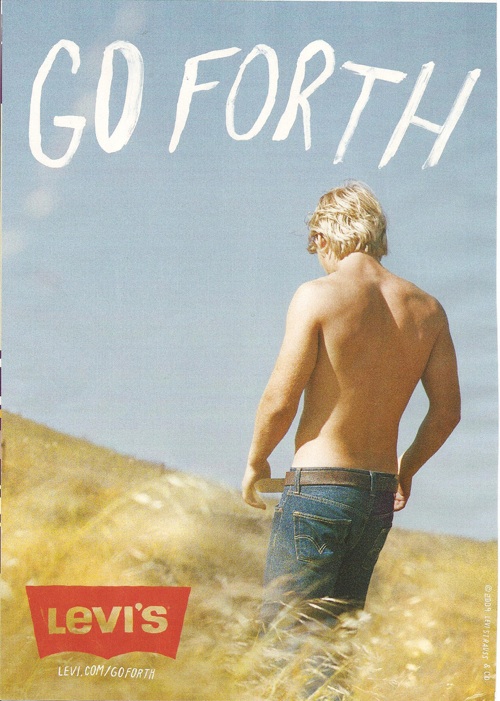

Fake authenticity begins with Hegel — or rather, with a text of Diderot’s that inspired Hegel. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) is the most important text in the pre-history of existential authenticity. In it, Hegel attacks the bourgeois “honest man,” whose self-seriousness and sincerity exemplifies a passive submission to a received social ethos. Believing that history can be seen as a progress toward a truly self-determining freedom, Hegel used the term base to mean “alienated from and antagonistic towards the prevailing ethos of society” — and applied it to the agent of this kind of freedom. Likewise, he turned noble into a pejorative, using it to mean “overly identified, internally and externally, with the prevailing ethos.” The anti-hero of authenticity spends his days, Hegel insists approvingly, “in universal talk and in deprecatory judgment which rends and tears everything.” At the very moment he wrote these words, somewhere else in time the glue-sniffing teens of Errol Morris’s Levi’s “What’s True?” ads were flickering into existence.

Hegel’s romantic portrait of the anti-hero of authenticity was deeply influenced by Rameau’s Nephew, a dialogue discovered after Diderot’s death in that philosophe’s papers. In it, Diderot appears as “Myself,” an honest bourgeois philosopher; and the Nephew of the title is his opposite number, a poverty-stricken musician who earns his keep in the homes of wealthy patrons by being himself: an insincere, buffoonish parasite. (Think Oscar Levant, without the neuroses.) The Nephew, Hegel, decided, was a prime example of the courageously base man — a disintegrated, alienated, distraught consciousness seeking a self-determining freedom. He pours out his irony on the bourgeoisie, mocking their earnestness, and exposing the constructed nature of their taken-for-granted ideas about truth, meaning, and morality.

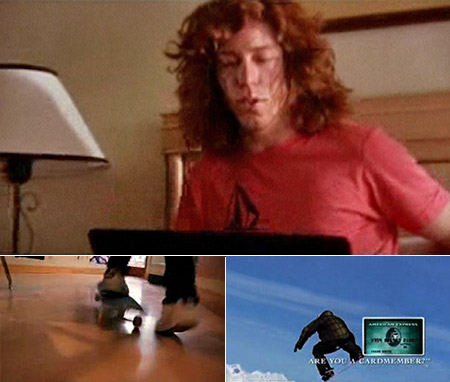

The Nephew does do all this, it’s true. But try reading Rameau’s Nephew after you’ve just read Thomas Frank’s The Conquest of Cool (1997), like I did, and it becomes immediately apparent that the Nephew rejects the prevailing ethos not in order to follow his own pathos (i.e. like a real anti-hero of authenticity), but because, as he puts it, “with the aid of vices natural to me [I have made myself] agreeable to the tastes of my patrons.” The solid bourgeois Diderot finds the Nephew’s company enjoyable not because he’s been revolutionized by this abject outsider, but “because [his] character stands out from the rest and breaks that tedious uniformity which our education, our social conventions, and our customary good manners have brought about.” The Nephew is a romantic rebel-with-a-small-“r,” through whom solid citizens can vicariously fantasize about surpassing the limits of their own freedom. Rameau’s Nephew is Jake Burton, the snowboarding pioneer whom Jonathan Dee (in the January 1999 issue of Harper’s) calls a hero of capitalist realism, because his “dissent” is perfectly tailored for the American Express ads in which he appears. Two hundred years before Fast Company, the Nephew is the hip face of capitalism, an architect of consumer dissatisfaction and of perpetual obsolescence. The Nephew, the original “boundary-testing, lifestyle-radical consumer” (a phrase Feed’s Gavin McNett turned recently), is not the first anti-hero of authenticity, but the first hero of fake authenticity.

The first anti-hero of authenticity? Contra Hegel, Kierkegaard has the narrator of Fear and Trembling suggest that the Knight of Faith “looks like a tax-collector,” “tends to his work,” and in the evening “walks home, his gait as indefatigable as that of the postman.”

“I can only follow my own path.” — Orestes, in Jean-Paul Sartre’s The Flies (1943)

“Follow your own path.” — SUV ad

Authenticity, as a mode of existence, is a struggle against received truths, inherited contingencies, any ideology (in the Frankfurt School sense of the word) which impedes the possibility of freeing oneself — and others — from all forms of oppression. But thanks to Hegel’s appropriation of Rameau’s Nephew as the first anti-hero of authenticity, authenticity itself has become a kind of ideology. In fact, as Adorno’s 1967 introduction to The Jargon of Authenticity puts it, one of the most pernicious forms of ideology is “a vague and noncommittal suspicion of ideology.” Welcome to the Nineties.

“The absurd man says yes.” — Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (1943)

Only too aware that the fake-authentic nature of daily life is an absurdity, in The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus concluded that the only possible alternative to suicide is poiesis, creation. For Camus the myth of Sisyphus, who must eternally push a block of stone to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back into the valley, is inspiring: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” he insists. The myth, he says, is not a lesson in futility, but “a lucid invitation to love and to create, in the very midst of the desert.”

Golomb, in his history of authenticity, describes Camus as “the last thinker on authenticity” — as though for some reason no one would ever be able to think about these issues again. But the philosophy of authenticity didn’t disappear when Camus died in 1960: it went underground. Baudrillard, who says that we’re living in an era in which the true “cancels itself in the truer-than-true, the too-true-to-be-true,” and the false “disappears into the too-false-to-be-false,” credits his discovery of fake authenticity to his encounter with the pulp science fiction novels of Philip K. Dick, this issue’s Hermenaut of the Month. It’s time for a general reconsideration (by individuals, not by the culture) of all things “plastic,” all things fake, all things mediated or inauthentic. Dick, whose writing explores the no-man’s zone between the too-easy poles of real and unreal, authentic and fake, is one place to begin.

What frustrates people so much about Dick is his habit of obsessively offering interpretation after interpretation for why the world is the way it is, without ever coming to any conclusions. But authenticity is not only a lucid recognition that the situation into which we find ourselves thrown is contingent, absurd, irreal… but an acceptance and affirmation of that situation. The authenticity-seeking ironist-artist knows that authenticity is not out there somewhere. It needs to be created. Authenticity is always a point of departure, never a destination.

* Alas, in the original published version of this essay, the Miles Orvell quote was attributed to George Orwell!

READ MORE about Philip K. Dick.

READ MORE essays reprinted from Hermenaut.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE