Radium-Age Eco-Catastrophes

By:

May 22, 2010

These days, SF thrillers in which natural disasters end human life as we know it are mainstream fare. But long before M. Night Shyamalan and J.G. Ballard flirted with autochthonic disaster, the authors of science fiction’s Radium Age (1904-33) speculated wildly, and sometimes presciently, about the possible causes of dire biospheric transformations.

During science fiction’s Golden Age (1934-63), scores of novels and stories depicted vast natural disasters. If 9/11 was the real-life version of a New York catastrophe we’d seen in SF many times before, Al Gore’s melting-glaciers slideshow in An Inconvenient Truth was, uncannily, only the latest of many global-warming cataclysms about which SF fans had read in Golden-Age novels about, for example, sea-dwelling aliens (John Wyndham’s The Kraken Wakes), nuclear testing (Charles Eric Maine’s The Tide Went Out), even the stalling-out of the Earth’s rotation (Brian Aldiss’s Hothouse).

[A version of this post originally appeared at io9.com, in May 2009.]

J.G. Ballard’s 1960s disaster tetralogy, and Golden-Age classics like George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides helped legitimate and popularize the eco-catastrophe novel. But the writing of the natural disaster is a Radium Age SF phenomenon. Richard Jefferies’ 1885 romance After London vividly depicted an England that had reverted to neo-medieval civilization after a Planet X-like “dark body” disrupted the Earth’s climate; and Camille Flammarion’s popular Omega: The Last Days of the World (1893-94 French, 1897 English) imagined the dissipation of the Earth’s atmosphere after a comet strike. The Panama Canal project also sparked fears: In 1890, H.C.M.W.’s The Decline and Fall of the British Empire was among the first of many portrayals of the disastrous effects of merging the Atlantic with the Pacific via the Canal. Still, it wasn’t until the early 20th century that the eco-catastrophe emerged as a literary sub-genre.

Here’s a rundown — in no particular order — of 10 eco-catastrophes from science fiction’s Radium Age that are particularly enjoyable, terrifying, and/or influential.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

1) PLANT-KILLING VIRUS, in J.J. Connington’s Nordenholt’s Million (1923; 1948 reprint shown here).

As denitrifying bacteria inimical to plant growth spread around the world, causing agricultural blight, British car manufacturer Jack Flint is invited to become director of operations at a huge survivalist colony located in England’s Clyde Valley. Superficially, Nordenholt’s Million is a direct precursor of John Christopher’s The Death of Grass (1956), and many other Golden-Age SF novels. [Similar Radium Age fictions include: Edgar Wallace’s The Green Rust (Aug. 7-28, 1919), and Charles J. Finger’s The Spreading Stain (1927).] But Connington is also issuing a timely warning — he was writing between the two world wars — about right-wing politicians and rapacious businessmen eager to use any disaster as an excuse to dispense with democracy, liberty, and justice. Flint discovers that his employer, the ruthless plutocrat Stanley Nordenholt, has blackmailed the country’s politicians in order to establish his stronghold, of which he becomes dictator in all but name. What’s more, Nordenholt’s henchmen purposely wreck what remains of British civilization, leading to scenes of horrific mass violence and agony; and the colony’s workers are treated like serfs. (Does this sound a lot like Ayn Rand’s 1957 novel, Atlas Shrugged, except not so favorably disposed to the industrialists and capitalists? Does to me, too.) In the end, the plant-killing plague comes to the end of its cycle. But things may never get back to normal. Nordenholt’s collectivized serfs — Connington was also worried about the Soviet Revolution — snap. They refuse to work, blow up the factories on which their fragile community depends, and join weird religious cults.

Fun fact: Connington was the pseudonym of Alfred Walter Stewart, the British chemist who coined the term isobar as complementary to isotope.

2) METEORITE, in Fred MacIsaac’s The Hothouse World (serialized Feb. 21-March 28, 1931; 1950 reprint shown here).

George Putnam, a science student who’s been in suspended animation since 1951, wakes up a century later in a technologically advanced utopia. He discovers that the domed city in which he now lives was built and stocked — by a foresighted group of scientists and their families — shortly before a comet struck the Earth in ’87. Much of the planet’s atmosphere was dissipated, and human and animal life perished in the new Ice Age. Alas, the utopian city turns out to be repressive (hello, Demolition Man, countless other examples). When it becomes apparent that there are habitable areas outside the dome, the population riots and Putnam attempts to escape, along with a dissident scientist and — of course — the president’s beautiful daughter.

3) DYING SUN, in Gabriel De Tarde’s Underground Man (w. 1884, p. 1896 in the Revue internationale de sociologie as Fragment d’histoire future, p. 1905 in English).

By the year 2489, Plato’s Republic has been realized, for better or worse: a worldwide neo-Hellenic culture of sophistication and creativity dominates; selective breeding is practiced; and weak and stupid individuals of every race are sent to fight wars. As a result, intuition and survival skills have been bred out of the population. So when astronomers determine that the sun is going out, the citizens of this dystopian utopia rapidly lose the will to go on. A sudden drop in temperature wipes out entire populations; the world is covered in ice and snow. Europe’s survivors flee to the Sahara and the Middle East, where the only plan their greatest minds can devise is an inadequate one: a huge, furnace-heated concrete bunker, situated over a rich coal deposit. “Of the beautiful human race, so strong and noble, formed by so many centuries of effort and genius by such an extended and intelligent selection, there would soon have been only left… a few hundreds of haggard and trembling specimens, unique trustees of the last ruins of what had once been civilization.” [I should point out that the survivalist bunker mentality is presented more favorably in other Radium Age fictions, including Clare Winger Harris’s “A Runaway World” (July 1926), Morrison Colladay’s “When the Moon Fell” (1929), and John and Ruth Vassos’s Ultimo (1930).] Humankind is saved when a fellow named Miltiades, whom the narrator describes as “one of those who piously guard, deep in their heart, the seeds of dissidence” (even in a utopian social order, that is), urges the others to tunnel beneath the surface of the planet, closer to the earth’s warm center. Once life has been established underground, a new civilization evolves. While every spring a few individuals who desire engagement with “nature” voyage to the surface of the planet, never to return, the rest of the populace prefer to contemplate artistic and scientific representations of the natural world. Recordings of natural life on the planet’s surface are discovered, but the underground men and women decide that artificial versions of these sights and sounds are far superior. Tarde’s Underground Man is, in other words, a prequel of sorts to Plato’s Myth of the Cave. So when a “madman” reports that he’s been to the surface of the planet, where he’s seen a revived sun melting the ice, the reader is not surprised when many of the citizens of this overly idealistic (in the Platonic sense) civilization refuse to investigate.

Fun facts: Tarde was a French sociologist, criminologist, and social philosopher who gave us such influential concepts as the “group mind” and economic psychology. Bruno Latour describes Tarde as “a truly daring but also, I have to admit, totally undisciplined mind.”

4) GREEN TECHNOLOGY, in Andre Maurois’ The Next Chapter: The War Against the Moon (1927; in English translation, 1928).

A meditation on the gullibility of the masses, and the dangerous influence of newspapers. Ben Tabrit, a great Moroccan scientist, invents a revolutionary “wind-accumulator”; this is in 1963, during a period of worldwide peace engineered by five benevolent newspaper barons known as the Dictators of Public Opinion. Thanks to a combination of worldwide boredom, the prospect of unemployment in the coal and oil industries (because of wind energy), and squabbling among nations about ownership of the world’s windiest places, a new world war seems imminent. Two of the DPOs conspire to avert war by uniting the human race against a common outside enemy. (Hello, Alan Moore’s Ozymandias.) The enemy? The imaginary inhabitants of the Moon, whom hoax newspaper stories soon accuse of wiping out remote villages around the world with powerful death rays. All goes well, and a Worldwide Wind Company is established. But then the scientist Tabrit invents a death ray of his own, and fires it at the Moon. Unfortunately, it turns out that the Moon really is inhabited, and the Moon-men blast the city of Darmstadt. The Earth retaliates. The novella’s final sentences: “On February 7th, the cities of Elbeuf (France), Bristol, Rhode Island, and Upsala (Sweden) were burned to ashes by the Moon. The era of Inter-Planetary War had begun.” Other eco-catastrophes involving aliens: Homer Eon Flint’s Out of the Moon (Dec. 1923 – Jan 1924), in which Lunarians plan to cause a solar flare that will incinerate or severely damage the Earth; and Flint’s The King of Conserve Island (Oct. 12, 1918), in which a war between Earth and its Jupiter colony is averted by a device that makes the sun go dim.

Fun fact: Maurois was a distinguished French litterateur.

5) CAPITALIST SCHEME, in William Wallace Cook’s “Tales of Twenty Hundred” (serialized Dec. 1911-May 1912).

In 2050, financial and industrial magnate Vincent Blake and his fiancée, Arlie Fortescue, dodge one kidnapping and assassination attempt after another as Blake proceeds with plans to stabilize climatic conditions by “straightening the axis of the planet.” Although Cook, a prolific dime novelist, tended to satirize Vernian romances whenever he turned to SF, in these six linked stories he’s earnestly imagining a future world improved by technology in the hands of benevolent capitalists. But is Cook in earnest? The Blake character would today be portrayed as a villain, while the kidnappers and hit men — who are agents of the Federated States of South America, the leaders of which are fully aware that Blake’s supposedly benevolent plans will benefit only his backers (the US, Great Britain, Germany, Austria, Scandinavia, Japan), and will create chaos elsewhere — would be portrayed as heroes. (Even at the time, fictional capitalists with climate-change schemes were suspect; for example, the shady protagonists of William Hawley Smith’s 1904 SF novel, The Promoters, who speculate in land that will become valuable once they’ve thawed the Arctic, are villainous. So are the Boston Irish crooks who attempt to profit from their advance knowledge of a chlorophyll-killing plague about to be visited on Earth from outer space, in George Allan England’s 1918 The Nebula of Death.) So don’t be fooled by Cook’s tacked-on happy ending, in which Martians — who heartily approve of Blake’s climatic-change plans — appear out of nowhere in order to rescue Vincent and Arlie from a trap. This isn’t, in other words, a romance-of-capitalism fable, or a straightforward Edisonade (like, say, George Griffith’s 1906 The Great Weather Syndicate, in which a robber baron and British inventor battle a sinister syndicate and also Kaiser Wilhelm in their race to control the world’s weather). Instead, “Tales of Twenty Hundred” is — or so I’d like to believe — a comedy of the blackest sort.

Fun fact: Cook cranked out 66,000 words a week, thanks to a semi-aleatory writing mode of writing whose secrets he later revealed in a gonzo fiction-writing manual delightfully titled Plotto.

6) THE PANAMA CANAL, in Louis Pope Gratacap’s The Evacuation of England: The Twist in the Gulf Stream (1908).

Despite geologists’ warnings that the Panama Canal will cause the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to merge, with cataclysmic results, the Canal is finished. (Canal enthusiast Teddy Roosevelt is one of the book’s characters.) Sure enough, entire countries must be evacuated because of climatic changes: “The sheltering power of the Gulf Stream was removed from Great Britain, and the frost of the Arctic world, so long repulsed, but now no longer compressed within the Arctic circle, expanded with instantaneous certainty, spreading the shroud of its killing cold over the same latitudes in Europe that for ages had slept beneath its spell in America.” The novel’s rather drippy protagonist, a businessman named Leacraft, is an eyewitness The Evacuation of England isn’t thrilling. As E.F. Bleiler notes, “Leacraft’s insipid romance is buried amid overlong didactic digressions.” But its depiction of a new Ice Age is eerily realistic.

Fun facts: Gratacap was a naturalist associated with New York’s American Museum of Natural History for over 40 years; when he died in 1917, he was head of the museum’s departments of mineralogy and conchology. Other SF novels: The Certainty of a Future Life in Mars (1903), The Mayor of New York (1910), The New Northland (1915), and the supernatural future tale The End – How the Great War was Stopped (1917). He also wrote works of theology (e.g., The Analytics of a Belief in a Future Life) and politics (e.g., Why the Democrats Must Go).

READ IT

7) MARTIAN INVASION, in Austin Hall’s “The Man Who Saved the Earth” (serialized Dec. 13, 1919; 1940 reprint shown here).

Opalescent globes of force appear across the world, removing large chunks of land and ocean. One such globe, in the course of sucking up enormous quantities of ocean water, causes the Gulf Stream to be diverted, among other changes with radical effects. Charles Huyck, a maverick scientist, realizes that Martians — whose planet is dying, as proposed by Percival Lowell — are stealing Earth’s natural resources. Devising a long-range solar weapon, Huyck disables the Martians’ globe-creating apparatus.

Fun fact: The Blind Spot, a novel that Hall wrote with fellow hack Homer Eon Flint, has been called (by Damon Knight) “the worst science fiction novel ever published.”

8) MAD SCIENTIST, in Murray Leinster’s “A Thousand Degrees Below Zero” (serialized July 15, 1919).

August, of a year in the near future: An extreme cold wave strikes New York, blocking the harbor with ice. Similar events occur in Gibraltar, Yokohama, elsewhere. A villainous scientist named Wladislas Varrhus takes credit for the cold weather, and threatens worse if he is not recognized as ruler of the world. Varrhus is ignored, until authorities determine that he has, indeed, mastered liquid hydrogen and superconductivity. Efforts are made to stop him, but they fail. Finally, Varrhus’s sinister black plane is shot down in an air battle. More Radium Age eco-catastrophes caused by mad scientists: Burnie L. Bevill’s “Restoring the Moon” (Sept. 1922), Leinster’s “The Storm That Had To Be Stopped” (March 1, 1930), and Edmond Hamilton’s “The Plant Revolt” (April 1930; a precursor of Day of the Triffids).

Fun facts: Murray Leinster (William Fitzgerald Jenkins) was a prolific pulp writer, one of the few SF writers from the 1930s to survive in the John W. Campbell era of higher standards; he’s credited with the invention of parallel universe (or alternate worlds) stories, as well as some of the earliest descriptions of computers and the Internet. He was also an inventor, best known for the front-projection process used in special effects.

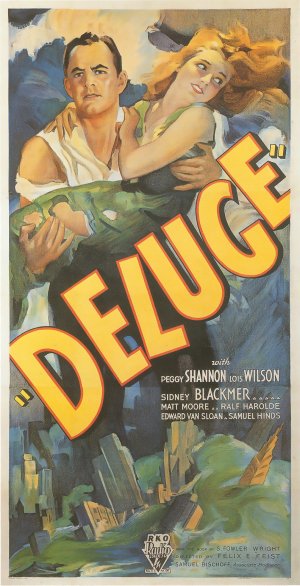

9) GEOLOGICAL UPHEAVALS, in S. Fowler Wright’s Deluge: A Romance (1927; 1933 movie poster shown here).

A global upheaval turns oceans into deserts, and sinks land masses everywhere except what remains of the English midlands, which are transformed into an archipelago. (Hello, Waterworld.) With a marked lack of idealism, Wright — who also translated Dante’s Inferno, and who uses this novel to criticize 1920s British society — tells the story of a new Adam and Eve: Martin Webster, a lawyer who attempts to find his wife; and Claire Arlington, an athlete (“like a valkyrie”) and one of the few women to survive the flood. The two store up food, fend off feral dogs, and battle sex-starved and flood-maddened miners, laborers, and vagabonds. If it wasn’t so un-cozy, you’d have to call Wright’s novel an early example of the cozy catastrophe — because the author is obviously thrilled that modern civilization, with its motorcars and bureaucrats, is gone.

Fun fact: A shocked Time Magazine review of the time contains a snarky description of Deluge. “Follows matter enough for a dozen penny dreadfuls, threepenny thrillers: a fight with sledgehammer and dirk in the lurid shadows of a gypsy fire-Claire’s body gleaming white but for the dark cords that bind her ankles and wrists; a struggle in the dank blackness of a railway tunnel which a gang of Claire’s suitors blockade at one end, while others sneak in opposite: ‘Kill the man, but save the wench! …’ A relic of civilized scruple holds Martin from killing a hairy giant furnaceman, because he has sprawled over the tracks and technically is down. But Claire sees the prostrate giant heave a rock, and, with no scruples, jabs him, hacks, thwacks, kills, saving Martin’s life.”

10) COSMIC DUST, in Bruno Hans Bürgel’s “The Cosmic Cloud” (German story published circa 1921; serialized, in English translation, Fall 1931).

A cloud of cosmic dust permeates the solar system, circa 2300, and most of Europe and the former north and south temperate zones are covered in ice. By the year 3000 life is nearly extinct, except in Africa, where a mixed-race civilization survives. A scientist, Johannes Baumgart, proposes a voyage to the Moon, because of his theory that intelligent life with advanced technology exists there. In a proto-Ballardian ending, the voyage is a failure. Earth is doomed!

Fun facts: Bürgel was a factory worker who studied astronomy in his spare time, and was eventually hired as an observer at Germany’s first public observatory. His 1908 book, From Distant Worlds; A Popular Science of the Sky, which argued that millions of inhabited worlds may exist within the universe, was a popular success.

ALSO OF INTEREST

Here’s a more complete list of Radium Age eco-catastrophes. For kicks, I’ve included stories and novels in which climatic and atmospheric change, weather control, and solar or “green” energy technology rate a mention.

NINETEENTH CENTURY (1804-1903)

* Faddei Bulgarin, Plausible Fantasies of a Journey in the 29th Century (1824)

* Edgar Allan Poe, “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” (Dec. 1839)

* Alexander Pitts Bettersworth, The Strange MS. By ___ M.D. (1883)

* Richard Jefferies,

* A. Bleunard, Babylon Electrified 1888 French, 1890 English)

* H.C.M.W., The Decline and Fall of the British Empire (1890)

* Chauncey Thomas, The Crystal Button: Or, Adventures of Paul Prognosis in the Forty-Ninth Century (1891)

* Robert Barr, “The Doom of London” (Nov. 1892)

* Byron A. Brooks, Earth Revisited (1893)

* John Jacob Astor, A Journey in Other Worlds (1894)

* Louis Boussenard, Ten Thousand Years in a Block of Ice (1889, French)

* Camille Flammarion, Omega: The Last Days of the World (1893-94 French, 1897 English)

* Lysander Salmon Richards, Breaking Up (1896)

* John Mills, “The Aerial Brickfield” (June 1897)

* H.G. Wells, “The Star” (1897)

* Otto Mundo, The Recovered Continent: A Tale of the Chinese Invasion (1898)

* Robert Barr, “Within an Ace of the End of the World” (April 1900)

* M.P. Shiel, The Purple Cloud (1901)

* George C. Wallis, “The Last Days of Earth” (1901)

* Fred M. White, “The Dust of Death” (April 1903)

* Ira S. Bunker, A Thousand Years Hence (1903)

THE NINETEEN-OUGHTS (1904-13)

* William Hawley Smith, The Promoters: A Novel Without a Woman (1904)

* George Griffith, The Great Weather Syndicate (1906)

* Louis Pope Gratacap, The Evacuation of England (1908)

* H. Percy Blanchard, After the Cataclysm (1909)

* Garrett P. Serviss, The Second Deluge (1912)

* William Hope Hodgson, The Night Land (1912)

* William Wallace Cook, “Tales of Twenty Hundred” (Dec. 1911-May 1912)

* Arthur Conan Doyle, The Poison Belt (1913)

* J.H. Rosny aîné, La Force Mystérieuse [The Mysterious Force] (1913)

THE TEENS (1914-23)

* George Allen England, Darkness and Dawn (1914)

* George Allen England, The Nebula of Death (Feb.-May 1918)

* Homer Eon Flint, The King of Conserve Island (Oct. 12, 1918)

* Edgar Wallace, The Green Rust (Aug. 7-28, 1919)

* Murray Leinster, “A Thousand Degrees Below Zero” (July 15, 1919)

* Austin Hall, “The Man Who Saved the Earth” (Dec. 13, 1919)

* Murray Leinster, The Mad Planet (June 12, 1920)

* Bruno Hans Bürgel, “The Cosmic Cloud” (1921 German, 1931 English)

* Burnie L. Bevill, “Restoring the Moon” (Sept. 1922)

* J.J. Connington, Nordenholt’s Million (1923)

* Hugo Gernsback, Ralph 124C41+ (1923)

* Homer Eon Flint, Out of the Moon (Dec. 1923 – Jan 1924)

THE TWENTIES (1924-33)

* Clare Winger Harris, “A Runaway World” (July 1926)

* S. Fowler Wright, Deluge: A Romance (1927)

* Charles J. Finger, The Spreading Stain (1927)

* Otfrid Von Hanstein, Utopia Island (1927 German, 1931 English)

* Andre Maurois, The Next Chapter (1927 French; 1928 English)

* Edmond Hamilton, “The Time-Raider” (Oct. 1927-Jan. 1928)

* Edmond Hamilton, “The Polar Doom” (Nov. 1928)

* Ray Cummings, A Brand New World (Sept. 22-Oct. 27, 1928)

* Morrison Colladay, “When the Moon Fell” (1929)

* Leslie F. Stone, “When the Sun Went Out” (1929)

* Ray Cummings, The Snow Girl (Nov. 1929)

* Olaf Stapledon, Last and First Men (1930)

* John and Ruth Vassos, Ultimo (1930)

* Murray Leinster, “The Storm That Had To Be Stopped” (March 1, 1930)

* Edmond Hamilton, “The Plant Revolt” (April 1930)

* Fred MacIsaac, The Hothouse World (Feb. 21-March 28, 1931)

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE