ROFLFAIL

By:

May 2, 2010

I spent most of Friday and Saturday at ROLFCon II, thrilled to be amidst the Internet’s elite creators and commentators. A conference devoted to the study, propagation, and celebration of memes, ROFLCon expresses — at least in the estimation of the conference’s organizers and its panelists and presumably many of us in attendance — the burning, beating heart of Internet culture. The sense of camaraderie in the lecture halls was high — we chortled at Pedobear, we snickered at Mahir and the Keyboard Cat guy, we boggled joyfully at the book and TV deals snagged by the likes of Lamebook and Texts from Last Night. A smorgasbord of tasty Internet goodness!

And yet at the end of each day, I left Cambridge with a crushing headache.

This morning I realized why.

The ROFL spirit is of Internet culture; it’s deeply woven into the outcast state of the tribes of Nerd and Geek. But it’s not the Internet tout court.

Snarking and hating and sniggering, laughing at the naïve and the noobs, the poor and the ignorant, the failed and the freakish — all this plays a huge role in life online. And it’s largely a salutary role. It keeps the Internet weird, it keeps it dangerous; it helps to remind people that whatever Mark Zuckerberg wants you to *think*, the Internet is not a private scrapbook. And when we laugh together at a funny accent or a tone-deaf singer or a baby biting his big brother, we’re having and sharing fun. And it’s a good thing, too!

The preferred term and the unit of measurement for this collective effervescence, the meme, is a highly problematic idea. But over and over again at ROFLCon, the meme was being celebrated as the source of the Internet’s power and influence, proof of its transformative potential, the currency and conduit of its subversive and politically challenging culture. And that’s just not true — at any rate, it’s not the whole picture. And by holding the meme as the Internet’s be-all end-all, we risk holding an idea of the Internet that cramped and incomplete.

Part of the problem is the idea of the meme itself. It’s a handy notion: that an idea is like a virus, a snippet of imaginal code coated in a protein coat of lulz that lets it slip in and infect one brain after another. And the Internet seems to make it real. But the meme has been a fraught concept from the time Richard Dawkins first analogized ideas to living things, making an association between concepts and cultural riffs that reproduce in our brains and the genes that reproduce themselves by natural selection.

But there’s more to an idea than its capacity to spread. There’s the nature of that spreading to consider, and the transformations it undergoes along the way. To semioticians, a meme — a copyable sign — is degenerate; it lacks the capacity to be translated and interpreted. Susceptibility to those abstruse qualities (translation and interpretation) only slow an idea down, hamper its easy transmissibility; but they also make an idea rich, increase its likelihood of enduring.

Although largely abandoned in the panels, a healthy critical note was struck at the start. Ethan Zuckerman and danah boyd opened the conference on a meta note, managing to think deeply and compellingly about the roots and potential of ROFL while maintaining an appropriately antic spirit.

In his half of the keynote address, Ethan Zuckerman presented the conundrum of memes emerge in the Internets of the developing world. He introduced the ROFLCon crowd to Makmende, a viral Kenyan superhero and the most important meme you’ve never heard of. Zuckerman asserted that although we think of our Internet as THE Internet, it’s not the only one. Oh, the pipes all connect, but languages and cultures remain barriers, not only at national borders but within them as well. Zuckerman seemed to want to argue that to be truly subversive, or at least to be politically impactful, memes need to cross these barriers. But the work of crossing takes translation and interpretation, and memetic culture is allergic to translation and interpretation.

It’s important not only to understand the Internet’s memetic quality, but to celebrate it. The symptoms of memetic infection include, but are not limited to, joy and collective effervescence. But the same energies that can make a celebrity of Mahir or bring millions of hits to a site like Awkard Family Photos can also promote smugness, groupthink, and quietism.

But the rest of the panels — at least those I attended — failed to live up to the promise. With brief obeisance to criticality duly dispatched, we moved on the real question: how to monetize your meme. Too often the tone was, “turn your snarky web site into a book — or even a TV show!” Still, there were bright spots: a panel on the Three Wolves Moon t-shirt consisted of consisted of Michael McGloin, art director at The Mountain; Brian Govern, the Internet user who posted the first review of the now-infamous t-shirt to Amazon; and Antonia Neshev, the illustrator whose work adorns the shirt. Not one of them is a member of ROFLcult. Govern, a law student, insisted on pronouncing “meme” with a short e, as “mem”— to barely suppressed audience guffaws. (His pronunciation made me think of the French word “même,” which makes an ironic false cognate for “meme”— no matter the meme, it’s always the same old thing.) McGloin, clad in a cowboy hat and a buckskin coat, gleefully argued that if the good old boys who buy his t-shirts catch a geek wearing Three Wolves Moon, they’re likely to kick his ass — but also expressed a sweet, genuine gratitude to the Internet for turning around his company in the midst of the recession. And Neshev, a Bulgarian purveyor of lowbrow Americana, showed that she had game by drawing cartoons of memes on the chalkboard.

I was struck by the strangeness of the scene: the supposed experts were in the audience, while the outsiders sat on the stage. And the audience throbbed with one question: how do we get some of that Three Wolves Moon mojo? How do we bottle it, aggregate it, monetize it? This hunger was poignant for the collective knowledge that turned those throbs to a shiver: memes come unbidden, naïve, unpolished; native to automated systems, they defy automation.

What ROFLCon lacked was the quality of awesome. People are doing amazing things on the Internet — beautiful things, unique things. How can you talk about Internet culture without talking about services like ffffound and aaaarg.org? Where is the joyous, collaborative Internet of a Robin Sloan? People use the Internet to find, share, and understand mysterious artifacts from the past, to tell stories in new ways, to share the joy they find in story, to search for extraterrestrial life and help figure out how proteins fold. The people with whom I attended ROFLCon, and several I met at the conference, are champions of this other, awesome Internet. They make lovely, telling art games like Sleep is Death and Björk v. Cthulhu. They create art projects that knit together virtual worlds and RL in strange and wonderful ways. They’re connectors, creators, and collaborators.

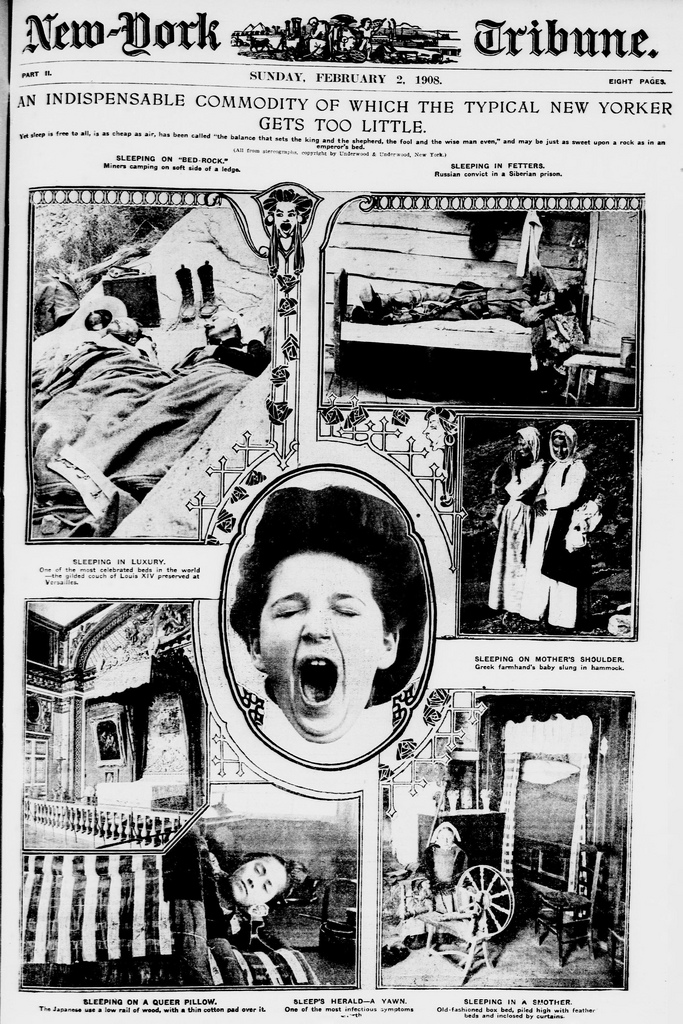

The Internet is amazing, and it’s not only about the lulz. It’s people working together to identify and describe thousands of photographs on the flickr photostream of the Library of Congress, or combing through satellite imagery for scenes of beauty and amazement, or sharing amazing examples of book illustration or vintage advertising.

It’s Infinite Summer and Ash Cloud Tales. They don’t all go viral, but that’s OK — in fact (and this is important) their power comes from not going viral. Infection isn’t the only way to influence, much less to create. Compared to meme traffic, translation, interpretation, and transformation may be the Slow Internet — but I have to think that whatever endures of Internet culture will need these qualities.

Don’t get me wrong. I think there’s a place for laughing at crocheted condoms and people falling down stairways and all those penises on chatroulette. And appropriation has a role to play in making culture. But schadenfreude is an awfully shallow source of self-confidence; and it’s neither the be-all end-all of the Internet nor the subversive force that ROFLCon would have us believe. Again and again, speakers and moderators asserted the enduring importance of this facet of Internet culture, its transformative potential, its subversive strength. And yet when pressed to name specific salutary effects, one speaker after another drew a blank.

Above all, FAIL and ROFL and SRSLY are not the only tags for Internet culture. Not only are hating and snarking not the whole of Internet culture, they’re far from its richest and most important strains. You’re right if you say, “hey — it’s ROFLCon, you highbrow hater. ROFL is what it’s about.” True enough. We need ROFLCon. But maybe it’s time for AWSMCon as well.