Golden Apples, Crimson Stew

By:

April 20, 2010

1534: A Spanish trader is returning to his ship in Seville after another unsuccessful attempt to sell his carefully tended hull full of tomato plants. The actual tomatoes that he’d brought had long ago rotted en route, and he’d had a hell of a time explaining to his customers what, precisely, the tomatoes were for. A farmer looking to sell his wagon load of garbanzos on the docks told him that his “tomate” plant looked like nightshade. Great. Further, he’d tasted the tomatoes himself and thought he must be missing something — the flavor was bitter and spare, and he was really wondering how he’d gotten talked into this cargo. Maybe they’d be better as decoration — all those yellows and reds, they were quite attractive.

He had a notion, though, that he could do something with them in Italy — but they’d need a better name, something mythological. With a sigh, he prepared to take his quickly wilting cargo to Naples.

Tomatoes, along with other New World crops like corn, chili peppers, and the potato (both sweet and non), were well documented by the early 16th century. Chili peppers took time to catch on with comparatively bland Old World palates, but were enthusiastically incorporated into Indian, Thai, and a number of African cuisines. Corn and potatoes became almost immediate staples the world over, but tomatoes took a surprisingly long road to popularity. The first recipe in a European cookbook (Lo scalco alla moderna, by Antonio Latini) containing tomatoes appeared in a Naples cookbook in 1692. Even considering the lag that you often see between usage and documentation, this has always been viewed as an astounding length of time for what is now a vital ingredient in such a range of cuisines.

The reasons given for this lag have been several: tomatoes are a secondary crop and fell in the shadow of the other New World imports; they were misconstrued as ornamental fruits and used for display (thus the golden apples, the pomodoro, of Italy); they were quickly recognized as a relative of the poisonous belladonna by peasants who refused to grow them (they are a member of the “nightshade” or Solanaceae family, along with chile and bell peppers, potatoes and eggpant) — but I propose another, more curious reason.

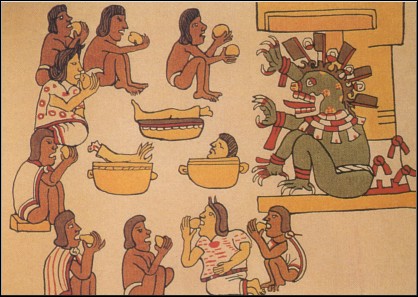

Population density in the greater Tenochtitlan/Tlatelolco metropolitan area had, by most estimates, surpassed 200,000 souls by the time Cortés arrived, making it one of the five largest cities in the world. Because of fear of famine, they were putting away such tremendous stores of grain, and concentrating their farming in maize to such an extent, that most of the population of Mexico was very slowly wasting away from malnutrition. Some scholars have used the serious protein deficiencies in the Aztec diet to suggest that they were supplementing their diets by eating one another. While there was widespread human sacrifice and cannibalism in the Empire, there is little to suggest that it was sufficient to supply meat to the general populace — and no records of human flesh at the Tlatelolco market (where an estimated 20,000–60,000 people used the market daily) exist.

The elite, however, were dining on the less fortunate, and probably to a significant extent. Estimates surpass thirty thousand sacrifices a year towards the end, and even more during the dedications of temples. Not all of these were eaten, obviously, but when they were, what were they eating people with?

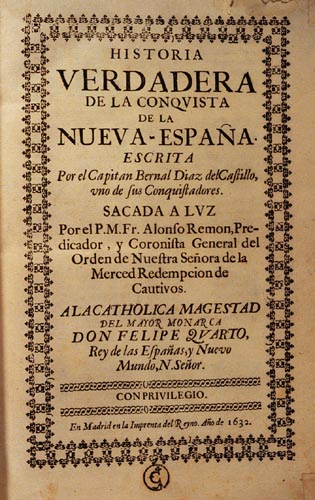

Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote a history towards the end of his life, Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (he finished it around 1578), detailing his time with Hernán Cortés in Mexico, the 199 battles that they fought in, and the events that precipitated the fall of the Aztec Empire in 1521. In his description of a march during 1519, Diaz inadvertently spills the beans (er, carne) on the tomato mystery. From Capítulo XXXIV, Cómo fuimos a la ciudad de Cholula en doce de octubre de 1519 años. Y del gran recibimiento que nos hicieron los naturales de aquellas tierras:

esperándonos, creyendo que habíamos de ir por aquel camino a México, para hacer la traición que tienen acordada con otra mucha gente de guerra que esta noche se han juntado con ellos. Que pues como en pago de que venimos a tenerlos por hermanos y decirles lo que Dios Nuestro Señor y el rey manda, nos querían matar y comer nuestras carnes que ya tenían aparejadas las ollas, con sal y ají y tomates, que si esto querían hacer, que fuera mejor que nos dieran guerra como esforzados y buenos guerreros

“…the recompense they intended for our holy and friendly services was, to kill us and eat us, for which purpose the pots were already boiling and prepared with salt, pepper, and tomatoes”

At first glance this seems a relatively innocuous, if gruesome, description, until you realize that what he’s depicting is a pot of chili only wanting meat. (When Diaz says “pepper” he’s referring to chiles, not East Indian pepper.) Remarkably, the earliest tomato recipe (by over 100 years) is also the earliest recorded chili recipe — and perhaps solves the age old debate, and correctly, as to whether beans belong in chili. Buried as it was in Del Castillo’s narrative, this episode has long been viewed as a key example of Aztec barbarism, rather than the singular culinary artifact that it is. There are relatively few recipes that have survived unchanged over the centuries, and to find that chili is one of them is remarkable.

The tomato, though, remains far more mysterious than the chile. Despite frequent depictions of feasting, cannibalism, farming, foods and the extensive depictions of medicinal herbs in the surviving Aztec Codices (a group of illustrated books depicting Aztec life before colonization, most written just after colonization), it’s hard to track down a picture of a tomato (there is widespread agreement that it should look more or less like a cherry tomato).

This despite the fact that Bernardino de Sahagún in his Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España (extracted from the Florentine Codex which he compiled) mentions tomatoes (both red and yellow) sold in the market (in Book 3) and has a description of tomato/chile sauces for mole poblano, red chile sauce and even a tomato based chile sauce for lobster (Book 8). (Sahagún’s Codex has at least a partial claim to the first tomato recipe as well — though it was compiled from later information, it was written down in the 1560’s, almost twenty years before Castillo’s.)

My grandfather was the same way with his “secret” ingredients for his baked beans and potato salad, always full of elaborate misdirections and red herrings — the former has never been discovered and is a great loss to humanity’s gastronomic tradition. The latter is celery salt, for the record.

Even in the depictions of maize worship, which typically have a wide assortment of complimentary foods pictured, it’s difficult to pick out any tomatoes.

It probably wasn’t conscious or a taboo against the depiction of tomatoes, just a tendency to keep tomatoes, so closely associated with ritual people eating, out of the limelight. Admittedly, it’s hard to draw little round things and make them look like anything.

From a gastronomic point of view, tomatoes, so good a match with corn-fed “long pig” (as human was famously called in Polynesia), would not have meshed as well with traditional European meats. The famous sweetness of human would have cut the bitterness of the tomatoes, leaving a more pleasing flavor than could have been obtained with beef, chicken, lamb or even pig (the taste most frequently compared to human flesh). Perhaps more to the point, the European aversion to chile peppers, invariably paired with tomatoes in Aztec cookery, would have made the tomato a difficult import. As any cook knows, the simpler a recipe is, the less fault tolerant it tends to be, and chili, here in its simplest form, was a four ingredient recipe — flesh, chile, salt, and tomato.

Even today – using tomatoes that have been bred for centuries for this use — a good sauce typically needs a bit of sugar, oregano, some salt and pepper, olive oil, bay leaf, basil, onion, and garlic — though, as any Sicilian will tell you, the use of some hot pepper will brighten up even the simplest sauce and make many of the other machinations unnecessary. Salsa is still often made with only three or four ingredients, though most commercial brands continue to add a great deal of sugar to make up for the absence of human flesh.

As he prepared to weigh anchor, wishing he’d had coin and space for a few barrels of bastarde, he wondered how with all the gold and silver lying about he’d ended up with a hold filled with plants. Thinking back, he realized that he’d just been caught up in the excitement — the feasts, the sacrifice , the peppers that scalded the tongue but somehow enlivened the soul. Tomatoes were made for excitement, not this sad tromping about on piers in the dying light of a Seville summer evening. He tried to remember that this cursed cargo, this humbled tomato, had once danced the Danse Macabre on the plates of Itzcoatl, Ahuitzotl, and Moctezuma.

Humano à la Azteca:

1 Medium sized person, quartered and beheaded

25 pounds fine tomatoes

10 pounds mixed chile peppers, whole

salt to taste