Pop Arcana (2)

By:

March 14, 2010

DON’T MIND IF I DO: a dialogue on Joanna Newsom’s Have One On Me (Drag City, 2010)

THE CHILD OF GOD:

The last time a Joanna Newsom record came out, I was roiling in a vat of emotional turmoil, a confusion that drove me restlessly toward refuge like the baby bird in Are You My Mother? I sought succor from pretty much everything that came down the pike: friends, billboards, sleep and beer and Precor machines. Then Ys (2006) came down the pike, offering balm without denial, a labyrinthine sympathy, a sonic retort where I found my feelings fixed, refined, and occasionally even redeemed. I was so marked by this record that I wrote, for free, a 10,000-word profile of Newsom for Arthur magazine, portions of which came back to me like uncanny spectres upon reading the recent New York Times Magazine piece on the musician. But no matter. It was the best love letter to music I ever wrote, and I wrote it out of my definite experience that records can heal.

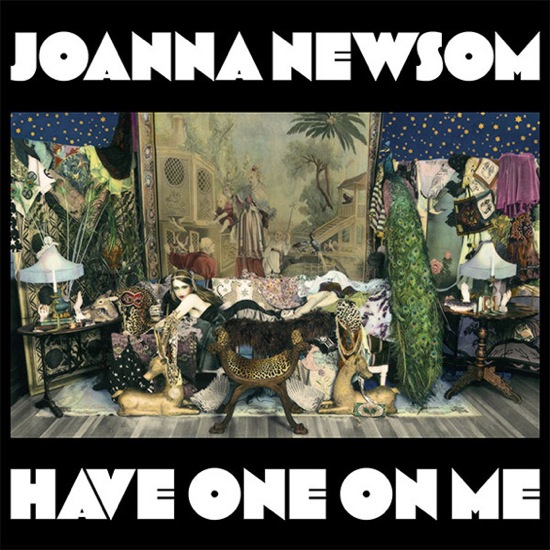

These days I find myself in more choppy waters, an older and in some ways grimmer man with no less need of visionary consolation. And so, at at 10 am on February 23, with the calm conviction of an acolyte, I gathered up some ripped and abandoned CDs and tromped down to Amoeba Records, where I promptly swapped them for Have One on Me. I got it on vinyl, natch, a chunky black box like Christ: the Album or All Things Must Pass. Someone had sent me a link to the MP3s days before, but though I wanted to get to the album as quickly as possible, in order to give myself a now-wasted shot at twittery relevance (chop! chop!), I waited until I could submit myself to the analog ritual. As soon as I got home, I sliced off the plastic wrapping, unpacked the discs, briefly admired Ms. Newsom’s admirable legs, and placed the first record on the platter. I dropped the stylus, settled onto the couch, and slowed down enough to float downstream.

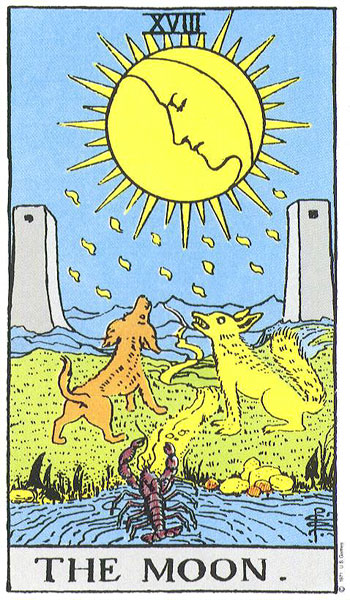

The sounds spilled out of my two skinny Mordaunt-Short speakers like the river in the Moon trump, passing between two dark towers. Glittering and plaintive, twisted and sometimes dull, Newsom’s music always flowed knowingly, disc after disc, down to that damn old sunless sea. Down to farewell. But the river invoked more than endings, those deaths of love and bodies that haunted Ys. At times the river called up the mountain source as well — not so much Joanna’s mercurial artistic intention or the “real person” behind the beguiling California child-mage avatar that she has constructed out of waxwings and gilded buttons, but something like the great and tender nerve that hums beneath all our emotional perception, that raw permeability of outside and in that Joanna has called skinlessness.

How does one speak of a record one plays for medicine, especially if one also belongs to that benighted tribe driven to analyze and to limn? That an artist of such copious originality as Joanna might also offer balm is a blessing, albeit one so personal as to render it, at least from a more critical perspective, moot. “My faith makes me a dope,” she sings in “Jackrabbits.” I know what she’s talking about. Faith is a corny move, even if sometimes it’s the only jimmy crack you’ve got. But there’s the rub: the second you sink your teeth into it, you must do more than feed. You must taste as well.

THE MAN OF TASTE:

Whatever its successes, Have One On Me provides a full clip of ammo for those already convinced that one of Joanna Newsom’s chief characteristics is her self-indulgence. Filling up three discs, the album runs over two hours long, and features a half dozen songs that swell towards the full ten-minute mark, a handful of which she would have done better to trim or to simply leave on the cutting room floor. There are hardly any lyric refrains, which means that words and images pile up and drift with sometimes logorrheac abandon, while choruses and verses couple in endless increase as the audience, or some of them anyway, admires. The lyrics can be as cryptic as those on Ys, but Ys was a masterpiece by any measure of sense or soul, an ornately organic webwork whose emotional and thematic control fully justified its difficulty and rewarded its many exegetes. Taken as a whole, in contrast, Have One on Me is a sprawl — a luxuriant cornucopia, for sure, but also a bit of a mess.

You can see the difference on the album covers. The painstakingly painted still life that announced Ys was redolent with the symbols — half revealed through careful listening, half hopelessly obscured — that held together the album’s holistic brocade of mourning. Have One On Me pictures Newsom in a claustrophobic theater of zoological curiosities and neo-hippie decor. Our fey heroine is no longer sitting up, stiff with a Mona Lisa smile. She lies recumbent, sultry, glass in hand, the mound of her ass book-ended by two leopards facing off on a pillow case. In the lower right there lies what I first took to be a small framed butterfly or moth, an echo of one of Ys’s key symbols, but a closer look revealed the thing to be two iridescent eyes clipped from the tail of a peacock — a stuffed specimen of which dominates Newsom’s menagerie, proud in its prodigal display.

THE CHILD OF GOD:

The balm Joanna offers wells up from her profligacy. The too-muchness of Have One On Me — the title, the run-on songs, the useless interludes, even the down-home cheesecake shots on the inner sleeves — are a kind of potlatch, an earthy celebration of excess despite and even because of the maziness and rot such excess implies. Rather than sustain the visionary control of Ys, Joanna here lets it all hang out, confident that someone out there, somewhere, will find a use for it. This is the “hour of effortless plenty” she sings about in “Esme,” a song that inspires a koan of gratified desire: “How do we know which parts of our hearts want what, / with such base generosity?”

In other words, the cornucopia swamps our fractured selves, filling in the gaps. Let go, embrace it all, taste the one taste. What makes such excess a balm rather than lazy decadence is its relation to origin, which is nothing less than our first fecundity. In The Man Without Content, Giorgio Agamben argues that the authentic work of art goes beyond taste by opening up the curious temporal dimension that belongs to our origin, a dimension that both transcends and precedes the usual flux of one damn thing after another. “By opening to man his authentic temporal dimension, the work of art also opens for him the space of his belonging to the world, only within which he can take the original measure of his dwelling on earth and find again his present truth in the unstoppable flow of linear time.”

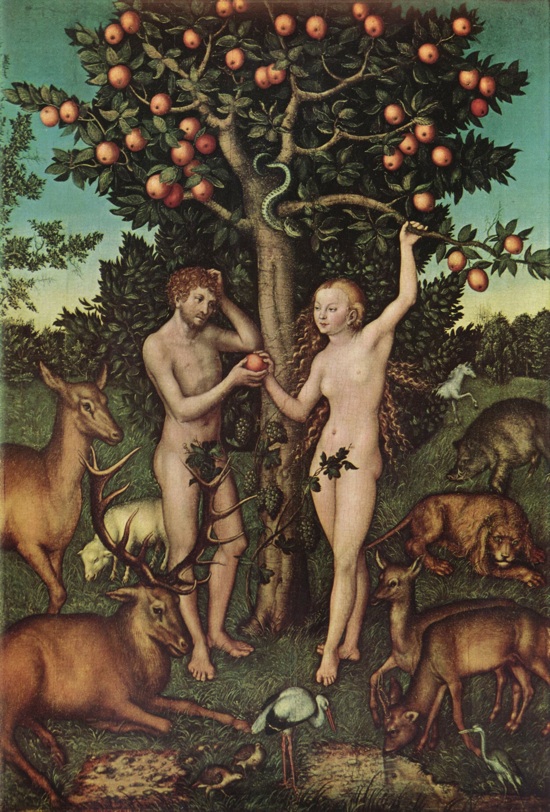

Joanna frames that original measure in “’81,” one of the strongest songs on the album, and, perhaps not coincidentally, one of its shortest. Over a solo harp, Joanna throws us into the garden of Eden, the soulscape of original profligacy. Like a pioneer, Joanna finds a plot of land there — not soil but “dirt,” marginal and low, like chaos, understood not as ruin but as the undifferentiated potential that allows us to reboot desire, to “start again.” She contrasts this state of pregnant potential, perhaps, with our present state of things, “hotter than hell,” a confusing fall of desire that impels her, like William and Catherine Blake in their garden, to strip down “naked as a trout” and regain some of that potlatch innocence.

In triumph she decides to throw a “garden party” in Eden, one that heals the great dualistic wounds of the Christian tradition — the heart-splitting “war between St. George and the dragon” — by inviting both sides along. (In the wilds of California, which saturate this album, we do not just befriend our demons — we party with them.) Embracing heresy, even as she plucks a sober lullaby on her heavenly harp, Joanna asks: “what is meant by sin, or none, / in a garden / seceded from the union in the year of A.D. 1?”

This is a core question of American Gnosis, a conundrum of antinomian innocence, and it is one I cannot pretend to answer. You’re just gonna have to plant your own little plot of land and see what grows. Here I just want to point out the pun that links “A.D. 1” — the first year of the Christian era — and the “’81” in the title, when Joanna — born in 1982, on the cusp of Capricorn and Pisces — was herself created from the union of her parents, an act that is, of course, both a continuity and a secession.

This is not megalomania — this is a rich harmonizing of origins, personal, religious, national. Puns are of a piece with Joanna’s excessive and often obscure wordplay, the delightful mania that impels her to describe waves as “dangling entrails from the gut of the sea.” But here this pun clears room for a disarmingly naked claim. With her matured voice sailing up into the empyrean, Joanna announces that she believes in innocence, and the wonder is that at that moment you — or me anyway — believe in it too. Such innocence is nothing less that the ability or drive to “start again” — not like Billy Idol in “White Wedding,” or the old American story of the reinvented self, but in the manner of that base generosity of spirit that allows us occasionally to proclaim, to one another, to ourselves: “I believe in everyone.”

THE MAN OF TASTE:

Newsom’s music is a crazy quilt stretched between the two pillars of the art song and the folk tune. The Milk-Eyed Mender (2004) tugged one way; Ys the other. On Have One On Me, Newsom quite consciously walks a middle path. It is an attempt to marry the ambition and scale of her material on Ys with the simpler and more accessible song forms that characterized her more hard-scrabble though finely executed debut. As she announces in the opening cut, she wants to be “Easy / Easy to keep.” Colorful and sometimes informal instrumentation replaces the careful drama of Van Dyke Parks’ orchestration on Ys, while the strong polyrhythms that peppered that album are nearly absent, transmuted into vocal lines whose beats skip across more conventional musical measures. We also find increasing use of the piano, an instrument Newsom wields with a charming and sometimes ham-fisted simplicity worlds away from her fleet-footed majesty on the harp.

In many of the songs, Newsom modifies her high style of moody brocaded balladry with down-home genre moves — blues, boogie, sassy ’70s horn charts — along with frequent and unexpected shifts from minor to the major key. The most successful expression of this last gesture — and one of the musical peaks of the record — lies at the close of the gorgeous “Autumn,” a haunted song of nostalgia and drift rich with mountain Californiana. At the close of the track, she invokes the melancholy of linear time: “Cannot gain ground / cannot outrun; / but time marches along.” Singing with a mind of winter, she shivers over a sad solo harp. “When the final count is done / I will be in my hometown.” But with that “hometown,” the music quickly blooms into a major-key bouquet: a cloud-splitting crescendo, a jazzy shrug of Ivesian brass, and a richly resolved figure on the harp, slightly undercut by a final fallen phrase. Wonderful.

That said, Newsom’s fusion of polarities — high and low, sadness and pleasure, demotic and fey — also explains the fundamental problem with this too-long record: songs largely based on smaller “traditional” forms that nonetheless go on and on and on. A few of the cuts begin with compact savor but become, by their weary close, a watery gruel that a crisp three-minute limit would have kept properly salted. “Baby Birch” is the worst offender here. It opens in rustic lullaby mode, short and sweet, and should have stayed that way. Instead, over the course of nearly ten minutes, the charm natters on, without genuine musical development or the pure repetition that Dylan, say, employed on his epics. When some distorted guitar begins to leak in, I hoped the song would start banging away like the art-folk tracks on Talk Talk’s The Colour of Spring (1986), but nothing much comes of it. We end with a cloying and exotic melody on the Bulgarian tambura, and then, in a manner unforgivable for an artist as composed as this, the tune simply fades out.

One of the beauties of sorta traditional popular song forms is, of course, their economy. From the point of view of the potlach, this is paradoxically their strength. The brilliantly concise can be more “generous” that the brilliantly prolix, since you get more for less. Listen to neo-trad songs like “Long Black Veil” or “Crash on the Levee” or “Ripple,” and you get a big rock candy mountain the size of a gumdrop. “On a Good Day,” the one diminutive cut on Newsom’s album, is a 1:49 dollop of what more of this record could have been. Four verses, a simple old-school rhyme scheme (AAAB, CCCB), and a wry emotional fusion of commitment, nostalgia, observation, and resolve. It’s small but it stays with you, like a marble in your pocket that reflects a different color every time you give it a glance.

THE CHILD OF GOD:

Why do the bereaved and bereft so often choose to listen to mopey music in the midst of grief rather than slapping on P-Funk or some glittering bauble by Mozart? The point is not, as is often imagined, to take refuge in shared sentiment, to “know you are not alone” in your hardship. When a depleted me turns to Nick Drake, it is not to relieve loneliness — after all, it is no relief to hang with a sonic simulacrum of some sad dead guy. I turn to Drake, or to new Newsom songs like “Go Long” and “Occident,” because the beauty and excellence of the art makes the emotions sounded by the music shine. The feelings do not disappear; they are rendered, through the old chords of sympathetic magic, shapely and reverberant. They become arrows rather than wounds.

In “The Awakening of Desire in the Classical Musical Work,” one of the most engaging and unusual articles in Visions of Joanna Newsom (2010), an engaging and unusual collection of critical essays and poems edited by Brad Buchanan, Robert McKay argues that both the story and the effect of Ys involve the tutelage of desire. Working with some Kierkegaard he says he first read in college, McKay argues that, in its awakening, desire passes through stages of dreamy narcissism and active hedonism to finally come to fruition in “the serpentine knowledge of desire’s necessary connection with suffering and death.” This theme — which is really a vision, and the richest of affects — courses through Ys but at first glance seems cloaked in the new one. As Joanna declares in “Easy,” she is now “worn to the bone by the river” — the river being a vital image in Ys of rough transformation, including the skinlessness that leaves the self behind. In many ways, Have One On Me is about putting on new flesh, a singer-songwriter quest for self.

But it is still a record of comings and goings, of shuffling between East and West, of dogs and violent loves and roads between. It is still a record where we begin to die the moment we are born. And it suggests at times another version of McKay’s serpentine wisdom, a vision of transience less beholden to Omar Khayyam’s carpe diem and more to what one might call the retrospective view. Most of the time we look at our lives from the point of view of the main character within a story; we struggle and choose and act, dividing and seeking good against bad. But if we are able to view our life retrospectively, from our deathbed as it were, then we can see it instead — as my pal Danny Castro puts it — from the author’s point of view. Gazing back at the life that is nonetheless before us, we see the whole story, the whole book of right on, and it is all one weave, not just the worm in the apple but the saint and the dragon, the desire and the pain, the spring and fall and the final mind of winter, for whom the self grows as transparent as ice.

This esoteric perspective touches a number of songs on the album in that fragmentary oracular manner that Joanna shares with few lyricists. “No Provenance” begins with a character who has died happy and lived to tell the tale, waking after a Rip Van Winkle sleep “to find me gone.” In “On a Good Day,” Joanna sees the “end from here” but chooses to “stay for the remainder.” The retrospective gaze receives its clearest statement in “Occident,” a gorgeous piano ballad that reminds me of an inky blue Joni Mitchell but with more diffidence. “All my life I’ve felt as though / I’m inside a beautiful memory, replaying / with the sound turned down low.” Towards the end of this great song, which might actually help you reframe reality, she holds out the possibility that “When I die, may I relate.” Relate (to) what? Is this the final relationship with the unity of things, the ultimate congregation in spirit, or is it rather the prerogative of the singer to relate, in death, a tale that can only then be told and done?

This question concerns us all, because we are all such tall tale-tellers, or should be. And what we relate, in our retrospective story, is our relations — in other words, our loves, the people, the poems, the animals, the land. This is the doubled moment Joanna captures in “Kingfisher,” a tune whose use of recorders and stately neo-medieval chords initially reminded me of — gasp — “Stairway to Heaven.” Two-thirds through this loosely apocalyptic number, over a solo harp, Joanna suggests a practice:

Stand here and name the one you loved,

beneath the drifting ashes

and, in naming,

rise above time

as it, flashing, passes.

These are end-times ashes, folks, both the grim fallout of dirty bombs that now threaten the bodies and imaginations of us no-longer-innocent Americans, and the flakes of a larger entropy, the refuse of the “loose universe” that is, in another tune’s memorable image, “rushing, unhinged, / toward diminishing lights, / like a headless caboose.”

But it’s the second half of this strange practice that rivets the whole record. In naming the time-bound love, the doomed relationship that calls us ever back into our story, we paradoxically rise above time, into that view that is both retrospective and original, the flash of return. Once again, Agamben hits the nail:

Just as all other mythic traditional systems celebrate rituals and festivals to interrupt the homogeneity of profane time and, reactualizing the original mythic time, to allow man to become again the contemporary of the gods and to reattain the primordial dimension of creation, so in the work of art the continuum of linear time is broken, and man recovers, between past and future, his present space.

And you know this in “Kingfisher” because you hear it: when Joanna utters the word time, the music bends, the pulse warps, and a glissando in the strings rises to a sustained pitch that forms the bed for the single most gorgeous and heartrending melody of this entire crazy-quilt album. The melody is carried by Joanna’s now more darkened voice, a phrase suggesting transcendence by being, for once on this babbling record, wordless. Here music alone, eagle-eyed, lets down a sky-hook for the sad-ass baby bird, still scrabbling for worms in time. The line lasts only a moment of course. But it’s the kind of moment you take to the grave.

Pop Arcana is a limited-run series of columns written for HiLobrow by Erik Davis.