Pop Arcana (1)

By:

January 30, 2010

One hundred years ago — or a hundred and one, depending on who you talk to — William Rider & Son, Ltd, published a pack of cards whose mysterious cartoons — the Tower, the Devil, the Fool — were destined to sink their roots into the dreaming loam of the 20th century imagination. At the time, Tarot decks were only found on the Continent, especially Italy and France, where the 78 cards were (and are) used for a popular trick-taking game as well as for fortune telling. Inspired by the notion that the cards encoded mystical knowledge, the occult scholar A.E. Waite, who also published an esoteric “key” to their meanings, spear-headed the design of a new deck that both honored and transformed traditional images that stretch back — at least — to the Renaissance courts of northern Italy.

Since its appearance, the so-called Rider-Waite deck has sold gazillions of copies, inspiring brooding hermeticists and teenage Goths alike, and stamping its enigmatic images onto such key 20th century artifacts as T. S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland,” the classic noir Nightmare Alley, and the inner gatefold of Led Zeppelin’s fourth album.

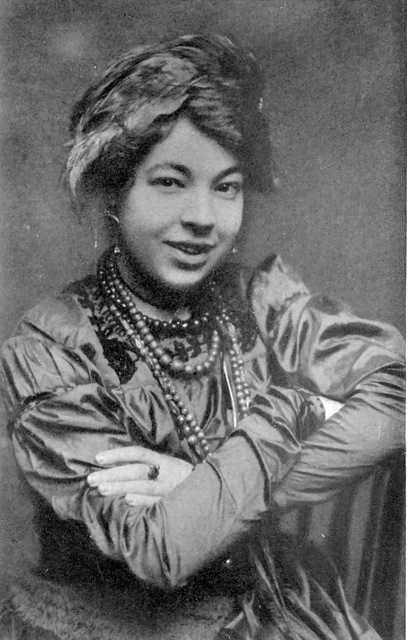

The Rider-Waite deck earns a so-called because the name — which has been trade-marked by US Games, the current (and controversial) copyright holder — ignores the artistic contribution of Pamela Colman Smith, an American illustrator and occult initiate whose nickname, Pixie, seems preternaturally on target in light of the most widely-reproduced photograph of the woman.

Because of Colman Smith’s contribution, the deck is increasingly dubbed the Waite-Smith deck; US Games has even issued a Pamela Colman Smith Commemorative Set that includes a “Smith-Waite” deck scanned from a rare set of cards acquired by the company’s president Stuart Kaplan (some speculate he placed Smith’s name first not only to thrill revisionist Tarot feminists but to more easily claim copyright.) I’d argue that the best name is the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, a moniker which still gives pride of place to the a key fact about this iconic storehouse of enigmas: its commercial availability. Like the Ouija board, another hybrid of oracle and game that popped out of the occult revival of the late 19th century, the RWS Tarot channeled hidden forces into the artifacts of popular culture.

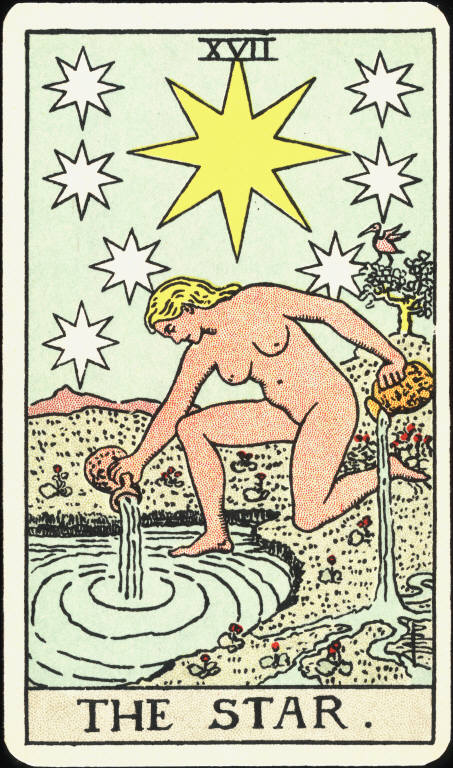

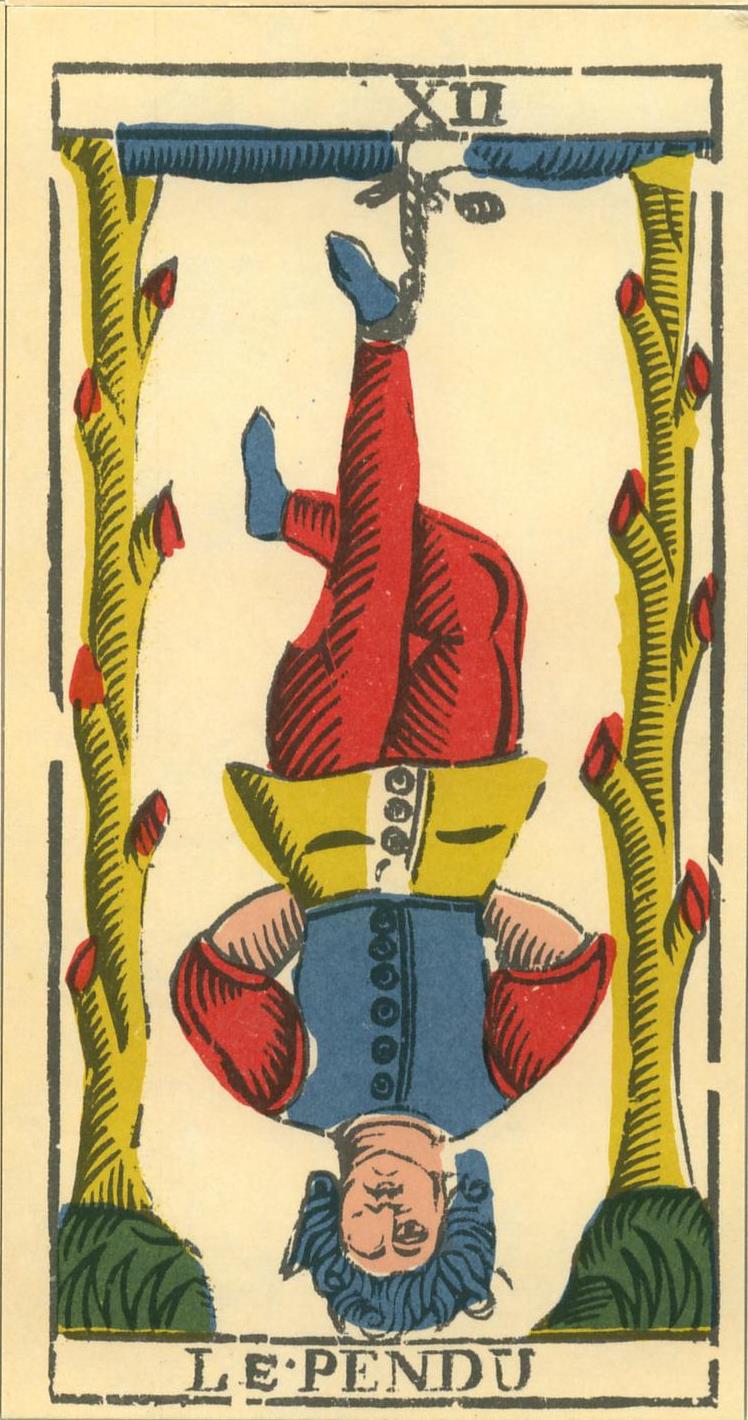

For readers who do not spend time with teenage Goths or hermeticists, some information may be in order. The majority of cards in a traditional Tarot deck are familiar enough: four vaguely familiar suits, with court cards and ten pips each. The oddities begin with the additional 22 cards that 19th century occultists called the “major arcana:” hieratic figures like the Star, the Devil, the Lovers and the Hanged Man.

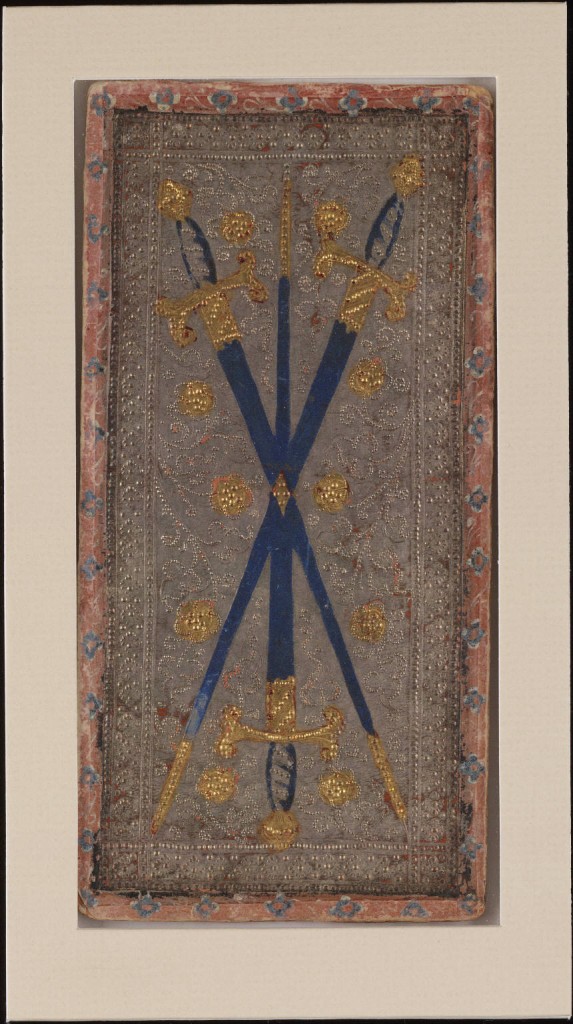

While these images feature a curious mixture of Catholicism, heterodoxy, folklore, and astrology, there is scant evidence that they encode any coherent mystical or “ancient” wisdom. As far as we know, the hand-drawn decks we have from the Renaissance were designed to amuse nobles with ordinary card games that first entered Europe in the fifteenth century.

The origins of European cartomancy are even less clear. One of the earliest references to card divination is found, in all places, in the diaries of Casanova. While in Russia, Casanova enlists a servant: a nubile 14-year-old country girl named Zaira who casts fortunes with a deck of cards on a daily basis. Inevitably the two become lovers and, almost equally as inevitably, Casanova’s actions impel in Zaira a jealous fury. “To convict me of my crime she showed me twenty-five cards, placed in order, and on them she displayed the various enormities of which I had been guilty.” The good man then tosses her “divining apparatus” into the fire.

Casanova was not adverse to divination, and occasionally applied numerological operations to the Romance novel Orlando Furioso in order to squeeze out divinatory messages. When it came to cards, Casanova preferred to gamble, which he did far more than occasionally. That said, the line between gambling and divination is not as clear as might first appear. After all, both embrace formal procedures (like shuffling a deck) whose results elude predictability; both, in other words, systematize the existential place-holder we call chance, producing events that, though outside of rational foresight, are nonetheless meaningful. Within the theatre of gambling, there is little sense of the truly random; instead, the passionate gambler walks a wayward path between method and prayer, pattern-seeking and pact. Fortune tellers, of course, insist that chance can also make sense, that a fall of cards can cast signs beyond our ken and mirror the patterns woven by fates or gods. Is not meaning itself a kind of luck?

It’s likely that Zaira’s readings of Casanova’s faults were more literalistic than esoteric — the square pragmatism of fortune telling rather than the hermeneutic circle of the occult. But however practical its aims, such soothsaying also loosens the mind for more archetypal fancies, which almost inevitably accrued around the cards. At the close of the 18th century, Court de Gébelin argued that the classic family of decks known as the Tarot of Marseilles was a veritable “book of Thoth” whose esoteric mysterious could be traced back to ancient Egypt — a land whose suggestive hieroglyphs, still undeciphered at the time, almost demanded the sort of speculative imagination that lures one into the occult’s labyrinth of phantasms. These phantasms received a much more thorough handling in the middle of the nineteenth century, when the French writer Eliphas Lévi, who almost single-handedly laid the intellectual foundation for the coming occult revival, ingeniously linked the Tarot’s major arcana with the circuitry of the kabbalistic Tree of Life. Levi’s lore was taken up in turn by the magical magpies who ran the Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult society centered in London that had initiated both Waite and Colman Smith, along with W.B. Yeats, Aleister Crowley, and Arthur Machen. Though rooting its authority in “cipher manuscripts” that linked it with a shadowy Rosicrucian order in Germany, the Golden Dawn did not, in reality, express an unbroken stream of tradition but practiced what Kathleen Raine called “an unbounded eclecticism.” Which is another way of saying that the Golden Dawn’s creative engagement with Tarot, ritual magic, hermetic Kabbalah, Egyptology, and Freemasonry was — like their inclusion of women into the order — eminently modern.

This point is important to emphasize, given the curious fog that cloaks our appreciation of the occult streams that animate the West. On the one hand, secular historians (and most of the better-informed adepts) recognize that the forms and even the content of much of today’s ancient or traditional lore are modern reconstructions rather than unbroken currents. We recognize, in other words, that Court De Gébelin was hallucinating his hieroglyphs, that Lévi was constructing the links between Tarot and Kabbalah. But this insight is often deployed for no other purpose than to expose the fantasies that, more often that not, “authenticate” occult claims through appeals to hidden tradition. It does not bloom into the more interesting (if more disturbing) conclusion: that the occult is now. The modern imagination — our imagination — is the theatre that stages these uncanny synchronicities, these resonances across time, these spectral encounters. This is the sort of serious play that Johann Valentin Andreae suggested when he used the phrase ludibrium to characterize the Rosicrucian mysteries he helped invent out of whole cloth in the 17th century, and that subsequently became an actual and deeply significant stream of Western esoteric thought and practice — including the Golden Dawn. The modern occult is at root an enchanted game, a round of hide-and-seek in a half-manufactured forêt des symboles. No wonder that one of the most popular vectors of the modern occult would be a deck of cards.

The paradoxes of the “invented tradition” are all over the RWS deck. For one thing, Waite made a number of significant changes to the basic template of the Tarot of Marseilles: he replaced the Pope with the Hierophant and the Papesse with the High Priestess; he “alchemized” the suits, with Coins becoming Pentangles; and he swapped the order of two major trumps in order to force a correspondence with the Golden Dawn’s hairy astro-hermetic theorizing. But though Waite acknowledged that he had departed from tradition, he pulled a typical occultist move — call it legacy bootstrapping — and argued that he had actually “rectified” the deck. At the same time, Waite also believed that the Tarot went beyond esoteric lore, and invited the user more immediately into the symbolic hero’s journey depicted by the sequence of the trumps. Waite was a populist as well as an adept, and he wanted his deck to be accessible enough to facilitate a direct personal experience of divine force. This intention, it must be said, is also eminently modern. As everything from William James’ 1902 The Varieties of Religious Experience to James Joyce’s contemporaneous collection of epiphanies suggests, the domain of intense and eventful subjectivity was becoming a central target of cultural activity.

Despite Waite’s emphasis on the major arcana in his widely popular Key to the Tarot, the most radical and influential aspect of the RWS deck lies, rather, in the depiction of the pips. Nearly all traditional decks use abstract designs to depict the numbered cards; the three of swords shows three swords and not much else.

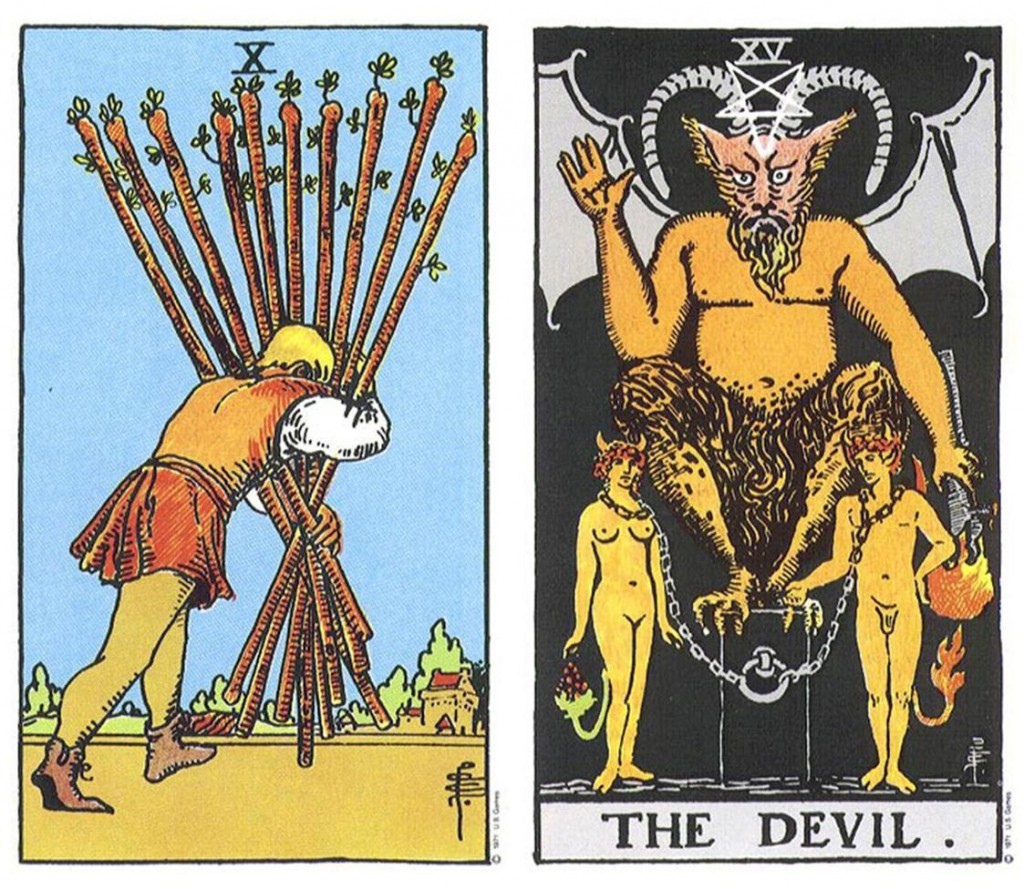

In the place of these ornamental counters, the RWS depicted dramatic scenes with human characters: a juggler, a thief stealing swords, a woman lounging in a garden. Because of their neo-medieval Craftsman vibe — a nod to William Morris and illustrated children’s books alike — these images may seem less radical than they really are, at least as far as the Tarot goes. Compare, for example, the image of the ten of wands to the Devil.

In contrast to the largely static and often symmetrical icons of the major forces, Colman Smith’s pips reframe the more “quotidian” realm of the minor arcana as a world of dynamic movement, of motion and emotion, as freeze frames of a world in flux.

Taking these pips into account, the RWS deck is anything but an obscurantist throwback to the spiritual hierarchies of the middle ages. Instead, it should make us think of the roughly contemporary emergence of film stills or comic book frames. Placed alongside Melies’ magic films and otherworldly comic strips like Little Nemo in Slumberland, which debuted in 1905, the RWS Tarot reveals itself as a snapshot theatre of mechanically reproduced phantasms whose dynamics lie as much in the relationship between frames as inside the frames themselves. In this light, even the oracular use of the Tarot can be seen, not so much as a capitulation to supernatural forces, but an affirmation of a kind of creative nonsense that forges connections between the isolated fragments of experience. In a plan for an unwritten book on Tarot, the San Francisco poet Jack Spicer — himself an heir to sacred Imagism and Dada alike — pointed out “the fact that the individual card has no meaning solely in itself but only in relation to the cards around it and its position in the layout — exact analogy to words in a poem.” Or at least, a poem that recognizes the contingency of its own construction. But even this may be too recondite, with the most fit analogy being the comic book.

Over the last century, the RWS deck proved enormously successful, defining the image of the Tarot for the English speaking world and much of the world beyond. Though many believe the RWS images are in the public domain, US Games — whose copyright claim is arguably based on the surrounding design of the backs rather the images themselves — has been cranking out “Rider-Waite” decks in a myriad of formats for decades. Expect more this year, although don’t hold your breath for the crisp facsimile of the original deck that hardcore Tarot fans have long wanted. Most experts are underwhelmed by the reprints in the recent Commemorative deck, and Smith’s original art remains lost. But the endless reproductions of Pixie’s images go deeper that the commodity form and into the world of artistic, if not archetypal, design. Her minor arcana images and situations created a template that continues to shape the zillions of Tarot decks that publishers have been cranking out since the early 1970s. Indeed, the widespread desire for a proper facsimile of the classic deck speaks to the work’s paradoxical status as an “original tradition.” Pace Uncle Walter, it also shows how much “aura” can still radiate from mechanical reproductions.

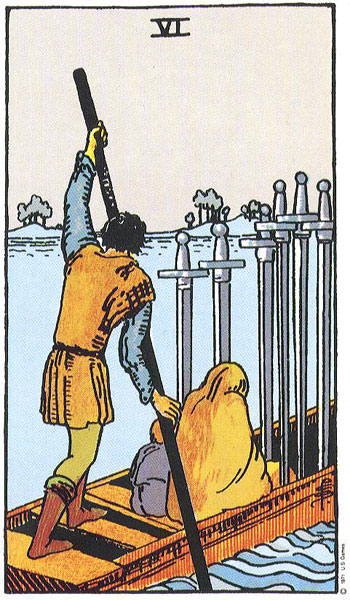

Whether Waite or Colman Smith were principally responsible for these images is an open question; given the scant and sometimes confusing comments that Waite makes about the pips in his 1911 Pictorial Key to the Tarot, some speculate that the scenes and images were largely the work of Colman Smith. This is particularly true with a handful of suit cards that Rachel Pollack, in her essential two-volume Tarot guidebook Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom, calls “gate cards”: cards which offer a complexity of imagery or mood than confounds the usual associations. As examples, Pollack points to the Six of Swords and the Three of Wands, both melancholic images that combine passage and passivity, water and facelessness.

Though clearly not as heavy with symbolic implications as cards like the Star or the High Priestess, they are arguably more enigmatic because they are more “open” — the empty enigma of a Bergman shot or a de Chirico timescape. Appearing in a reading, they confound one-to-one correspondences; they ask us to drift into ambiguity.

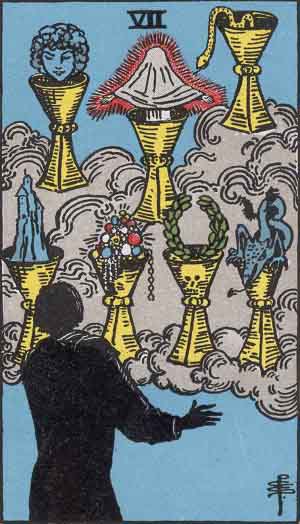

One of my favorite Colman Smith images, though, is also the deck’s cheekiest: the Seven of Cups, whose conventional attribution is illusion or fantasy.

Rough-hewn and awkward, the card features what appears to be a contemporary (rather than neo-medieval) man cowering before a series of apparitions. The phantasms themselves — jewels, a young woman, a crown of glory — are precisely the sorts of “low” objects of fantasy and desire that drive storefront fortune telling and pulp astrology columns. The cloaked figure, for example, is almost certainly a Spiritualist medium — a mystic type generally held in low regard by hermeticists like Waite, and which therefore lends the licking snake to the figure’s right an ironic bite.

The deeper irony, though, is that Waite and Colman Smith’s collection of transformative images would in turn typify if not define the low-rent stream of the popular, rather than esoteric, occult. The most important books on Tarot in the early twentieth century — besides Waite’s key, there is Paul Foster Case’s recondite book The Tarot — cobbled together esoteric correspondences and largely ignored divination, the informal and largely feminine tradition uniting Casanova’s spurned servant girl with today’s Colman Smith fans. But Zaira would have her revenge in 1960, when Eden Gray published her immensely popular book The Tarot Revealed, initiating a stream of down-and-dirty how-to books that insured that the Book of Thoth would sustain the hi-lo dialectic that, at the end of the day, drives the deck’s resilient power: at once a visual arcanum of hermetic lore and a quick-stop shop of oracular aid. The High Priestess who comes early in the sequence of trumps clutches an ancient scroll of “Tora,” a hand-scribed parchment of mysteries that invokes the “Taro” we clutch as well. But the image we hold is just a cheap reprint, a comic book trading card, a manufactured veil of mysteries that fits in the palm of your hand.

Pop Arcana is a limited-run series of columns written for HiLobrow by Erik Davis.