The Parnassus of Titon du Tillet

By:

January 8, 2010

At Pazzo Books, the shop my brother Brian and I keep in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, I’ve learned that old books are funny things. Often you catch them looking at you sideways, across a room, and it occurs to you to wonder what they’ve seen; where they’ve been; what odd parade of owners they’ve survived; or on what forgotten, dusty, shelf they were left to deteriorate over the centuries. Typically you can only imagine, but once in a very long while a book wanders through with enough information stored in it, in bookplates, inscriptions, and ephemera, that you can piece together a narrative.

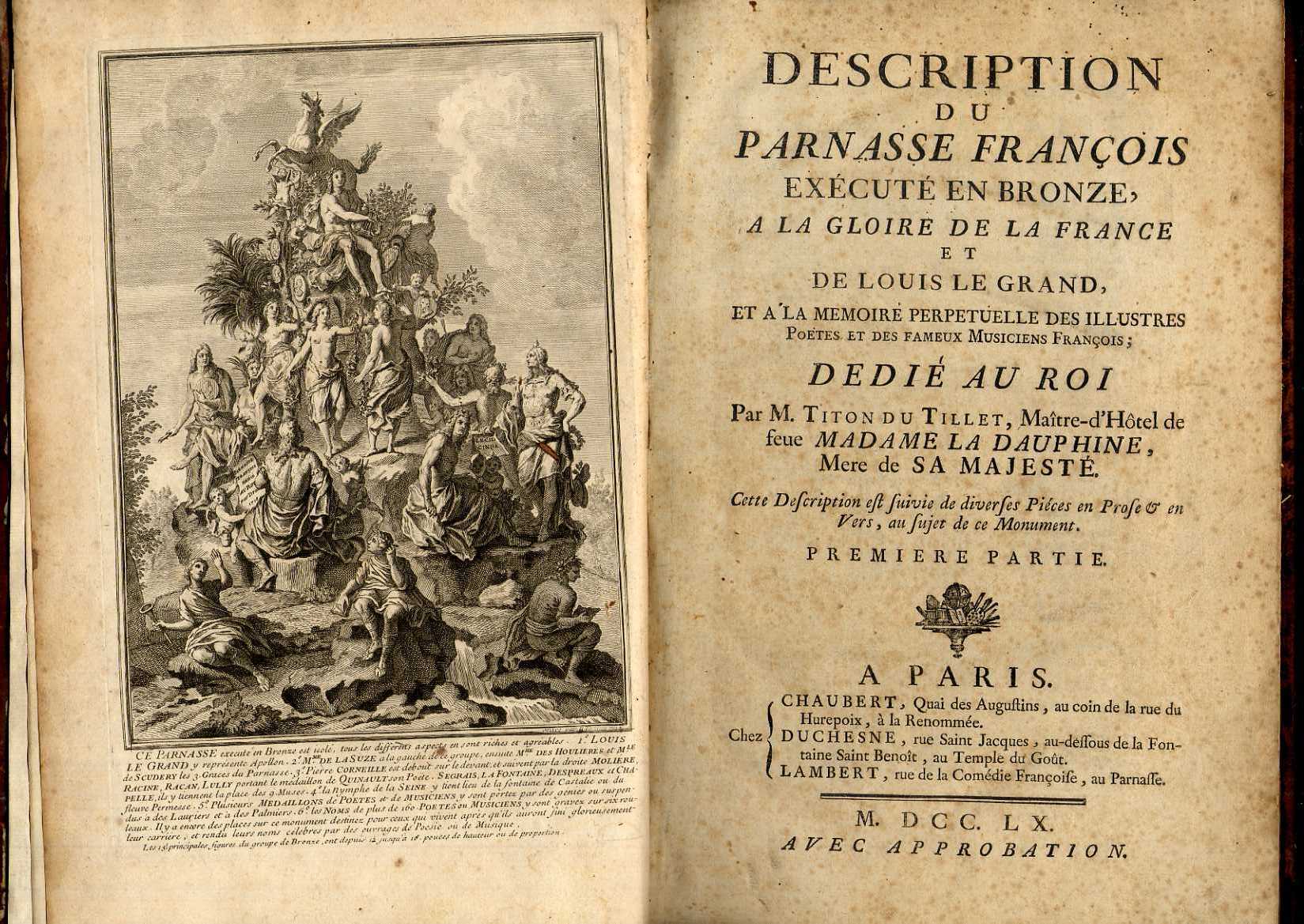

Évrard Titon du Tillet, great patron of the arts, son of Maximilien Titon de Villegenon, secretary to Louis XIV and alleged Scotsman, plotted to build a vast sculpture garden to celebrate the great writers, dramatists, artists, and musicians of France. Originally planned around a bronze statue, a model and description of which was executed in 1718, the project soon incorporated dozens of artists, growing to resemble a great folly (a penchant for which ran in the family; the Titon family mansion was called La Folie Titon). The budget swelled to 2 million livres and Tillet was forced to abandon the project.

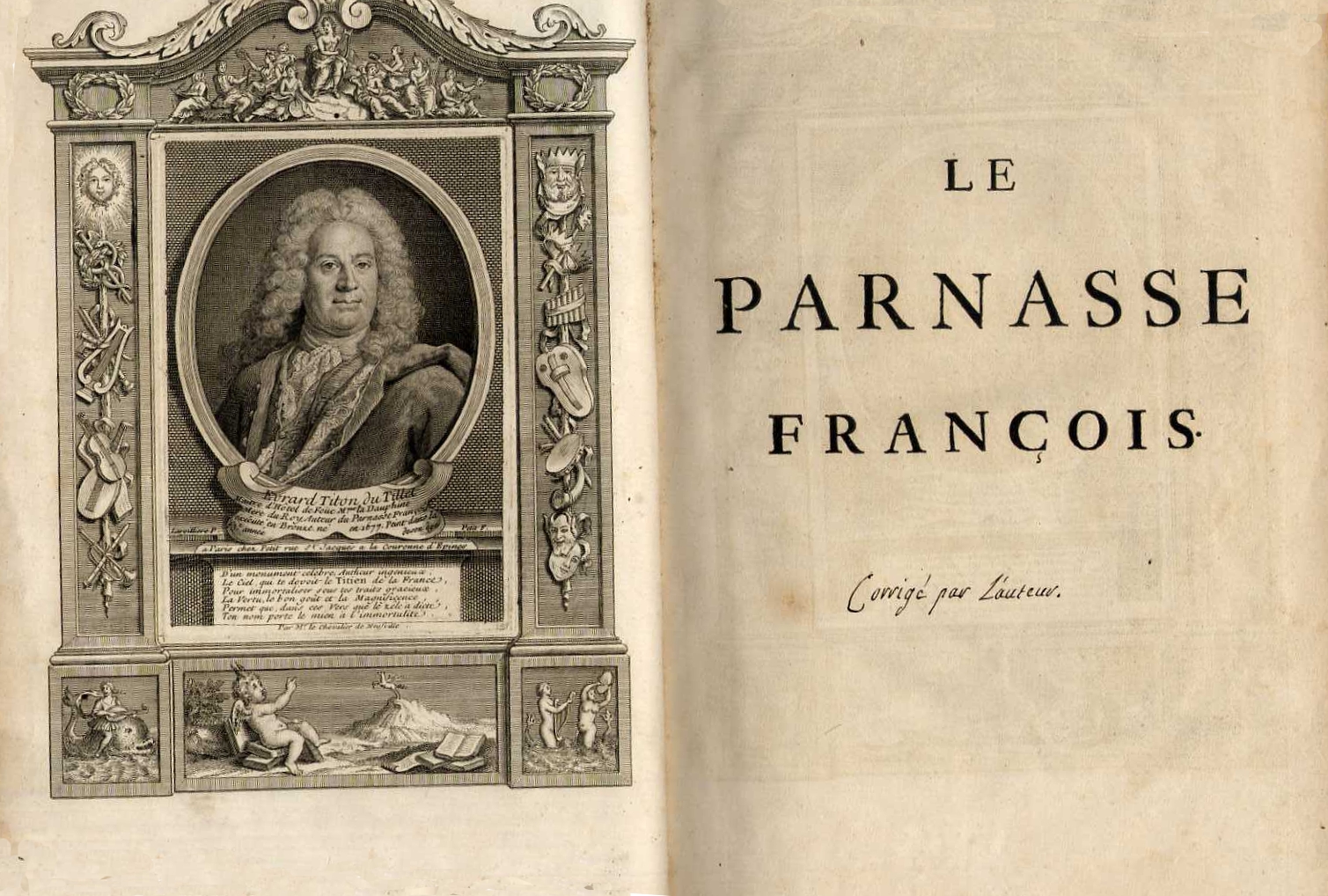

Instead he turned his Parnassus into a book, the first and largest installment of which appeared in 1732. Additions, often occasioned as artists died or gave up their craft, appeared in 1743, 1755 and 1760. This particular copy has the 1732 edition bound together with the 1743, and a second volume contains the 1760 additions. The 1755 was lacking. It’s a tall book, in folio, bound in heavy calf — a consequential volume. It has seen better days; the front hinge is weakening a bit, as is frequently the case with heavy books, but remains attractive and reasonably sure of itself. The five raised bands on the spine are not, as is now common, for show, but to conceal the cords that hold the covers of the book together. The gilt lettering and design on the spine is rubbed and dulled, but remains bright enough to be charming.

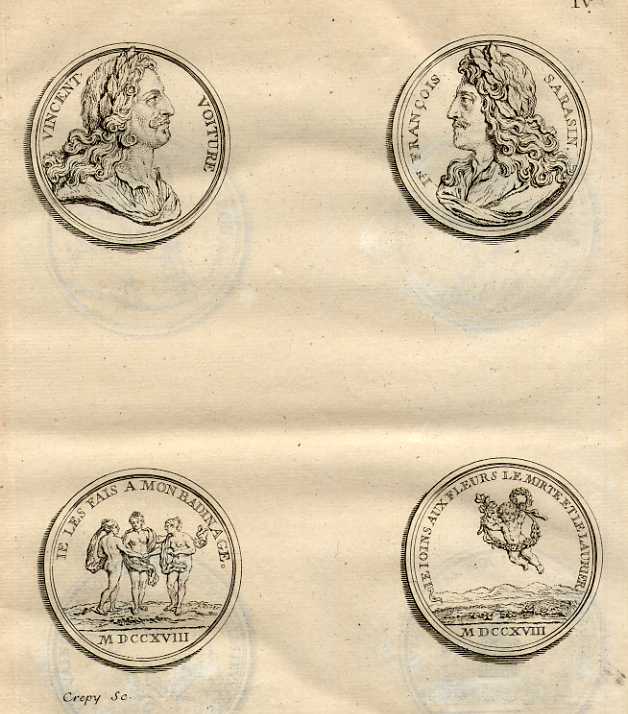

The caption to the frontispiece explains the arrangement of the statue: Louis Le Grand is Apollo with the three graces represented by Madames De La Suze, Houlieres and De Scudery. Corneille is in front with Moliere, Racine, Racan and Lully. Other less august personages are represented by medallions — these are also reproduced in engravings.

The book is important for two reasons, and, as you might expect, neither of them has anything to do with the right worship of French genius. Titon de Tillet’s project is one of the first attempts at a public sculpture venerating genius. Now we take this sort of thing for granted, but at the time it was groundbreaking and, apparently, inaccrochable (as Gertrude Stein used to say — unpublishable, more or less). Most crucially though, Le Parnasse François records a great deal of history on second- and third-tier artists for which there is no other source of biographical information. In his attempt to celebrate the immortal, he retained a record of the more easily forgotten as well.

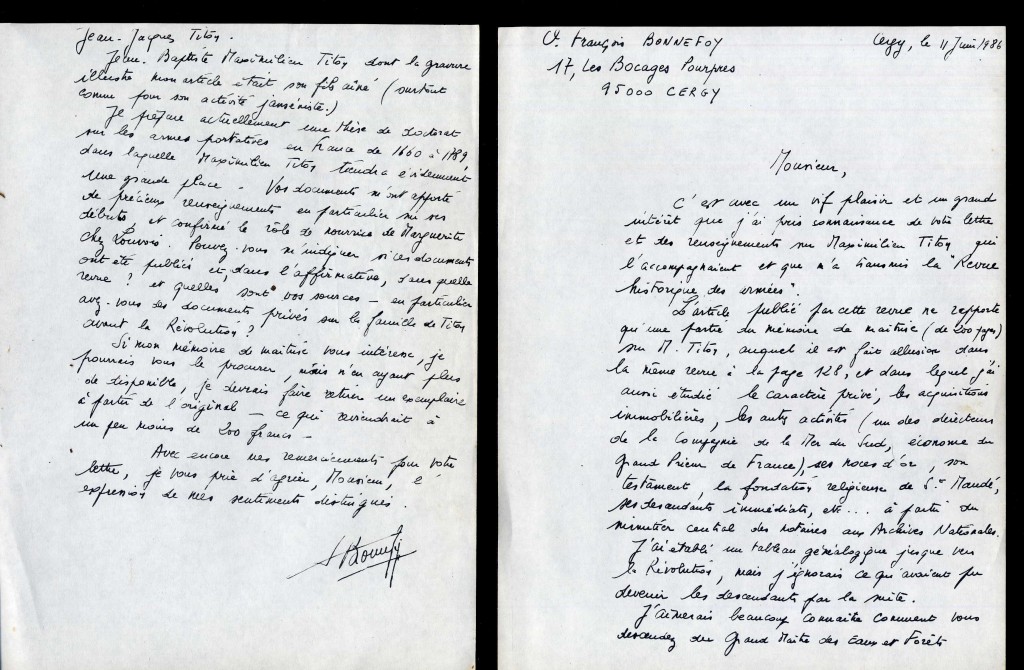

But this is all preliminaries, a mere back story to the story of this particular volume. It was written in 1732, though this copy, apparently, was not bound up until the 1743 supplement appeared. On the half-title page, across from the engraved portrait of Titon de Tillet, is written “corrigé par l’auteur” and the author’s manuscript corrections appear a dozen or so times in the margins, making minor corrections to the text.

Inside the front board is the armorial bookplate of Titon du Tillet’s great nephew, M. Titon de Villotran. Titon de Villotran (1727–1794) was a member of parliament and Counselor of the Grand Chamber. Certainly the volume must have been given to his father, the author’s nephew (explaining the authorial corrections which, while not uncommon at the time, were probably not affected on every copy), from whence T. de Villotran came into possession of it; or perhaps he was simply given the book for his 16th birthday. In either case, the volumes stayed in Paris and in the family.

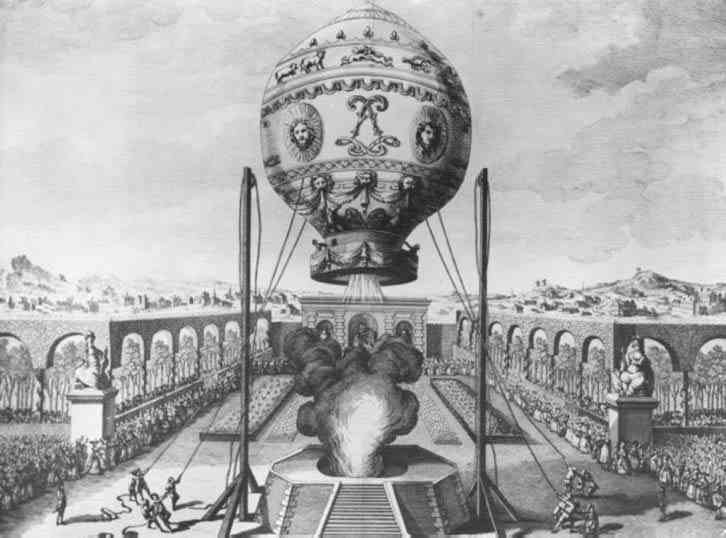

Three years after Titon du Tillet’s death in 1762, the family mansion was sold and turned into the Royal Wallpaper factory under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Réveillon. In one of the first outbreaks of violence, in April of 1789— three months before the storming of the Bastille — workers stormed Folie Titon and burned it to the ground. Villotran would have been 35 when his great uncle died, 38 when Réveillon turned it into the celebrated but ill fated manufacturer of expensive wallpapers. When burned to the ground, the former Folie Titon and now the sumptuous Réveillon residence was reported to contain over 50,000 books. Perhaps these volumes were still there, perhaps they’d never been given to his nephew, never formed the backbone of an odd birthday present — ending up in Titon de Villotran’s possession after being rescued from the conflagration. M. Titon de Villotran was safely across town, though, a member of parliament, counselor of the Grand Chamber and a notoriously hard man. But his safety was short lived — as in so many other cases, his success in surviving La Révolution only led to an unkind end during La Terreur. In prairial, year 2 (September, 1794), Titon de Villotran met with the guillotine.

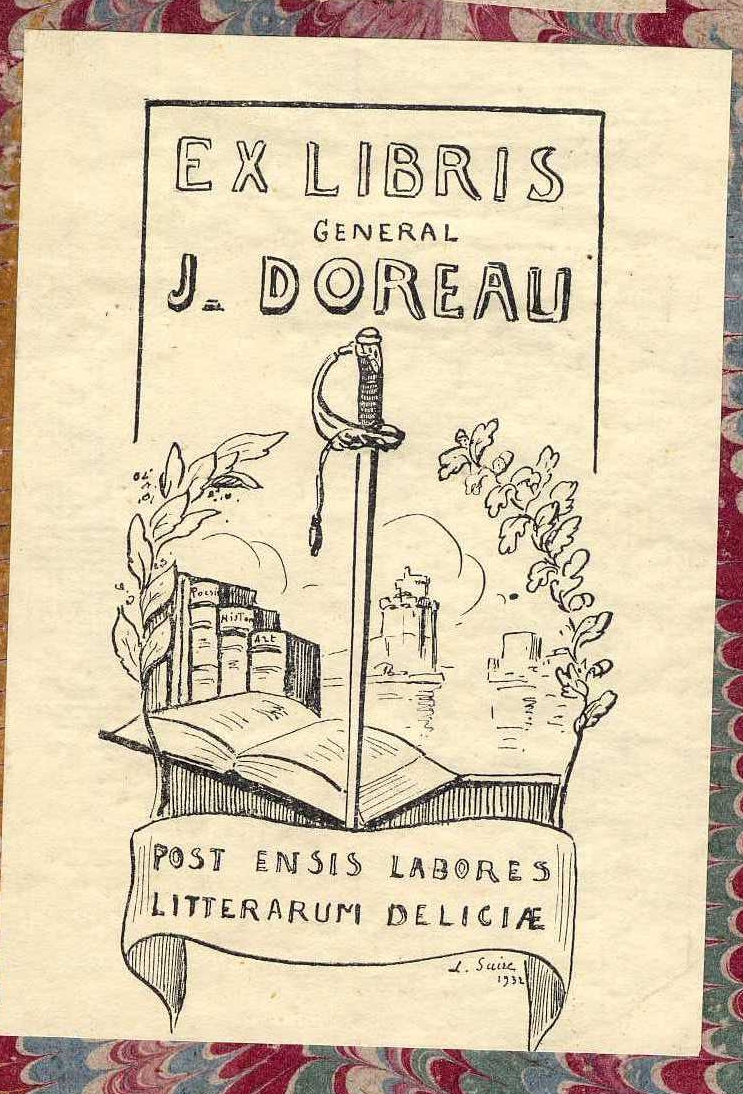

We’ll never know how the books escaped Villotran’s fate (speaking metaphorically, of course; The Terror rarely dallied to guillotine books). But a note to the back of an endpaper “De la bibliothèque de L.M. Lepbib (?) Lieutenant Géneral de Nemours” suggests that they made their way to Nemours, just outside of Paris. Perhaps they crossed the Atlantic to America in 1799 when Nemours’s most famous son, Eleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours, made his way to Delaware, though this seems unlikely. Pierre and E. I. DuPont were staunch royalists though, defending Louis and Marie in 1792 and being sentenced to the guillotine under Robespierre — a sentence that was still pending when Robespierre fell, though, after the DuPont mansion was sacked in 1797, they decided to stop taking their chances. I’d dearly love to report that Lieutenant General (”Bad Penmanship”) Lepbib met some unfortunate and unlikely end (as the author’s house was burned down by an angry mob and their first owner guillotined, a third might have brought us to genuinely cursed), but we will have to settle for the DuPont’s home. When we pick up its trail again, the book is in the library of “General J. Doreau.”

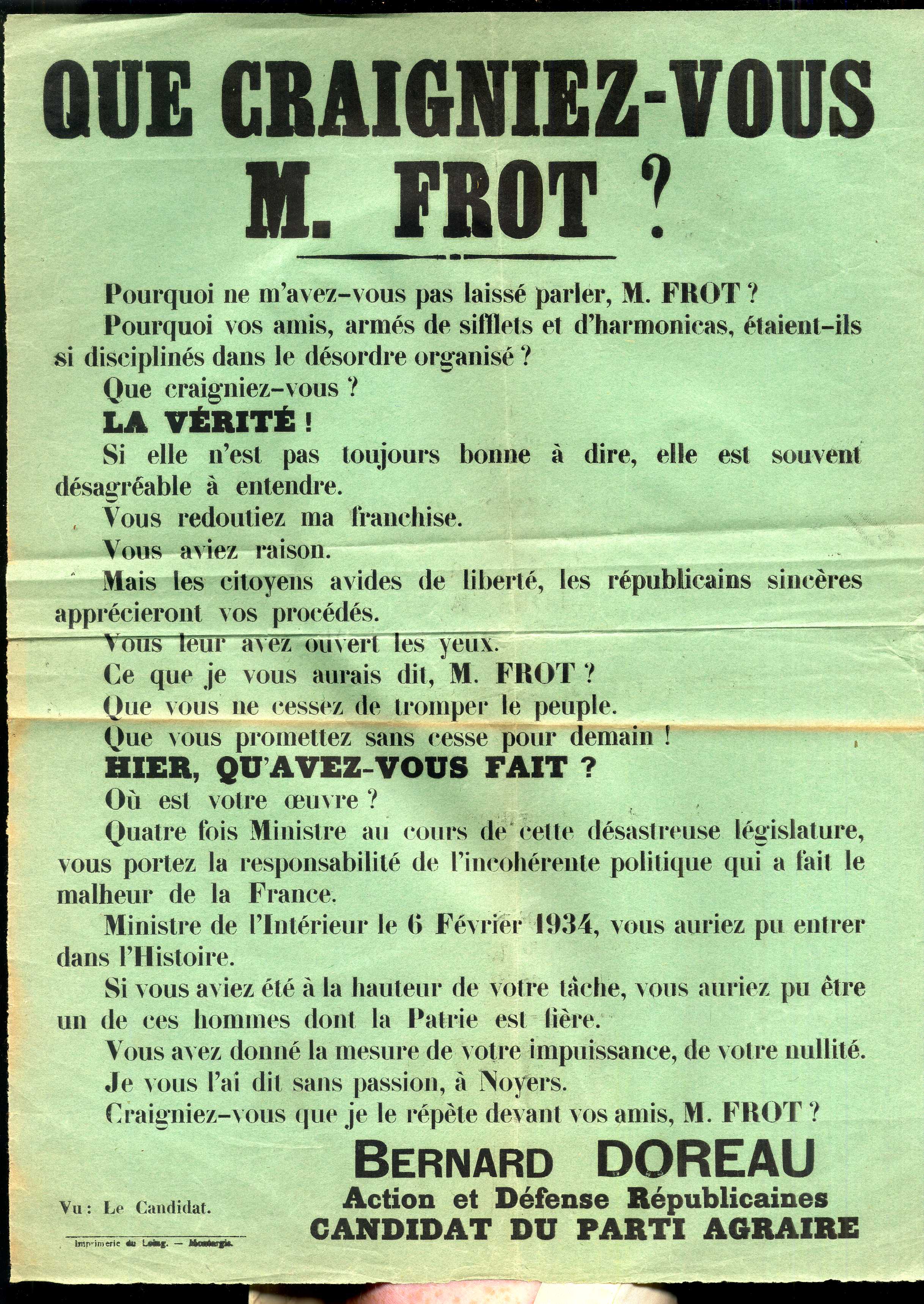

General Doreau’s motto, “After the work of the sword, the delight of literature,” is pretty nice, but he’s a dead end. Nothing about him is easily accessible (except for his well-dispersed bookplates, which show up occasionally on expensive books). However, his brother was Bernard Doreau, and here’s where it gets interesting: Bernard Doreau ran for office under the Parti Agraire, a right wing populist part formed in 1927. In this 1936 campaign poster, tucked into the 1760 volume, he was either running against, or using as a straw man, one Eugene Frot. Frot had been Minister of the Interior during the “February 6 Crisis”, A populist and a proto-fascist (and also, variously, xenophobic, antisemitic, anti-freemason, anti-capitalist, and anti-democracy) uprising — the largest single participant of which was Action Française, the angry offspring of the Dreyfus Affair, a pro-monarchy movement (it’s important to be FOR something) The uprising brought about the resignation of the left-center prime minister on February 7. It is frequently identified as the most fragile moment for the Third Republic, the French government which ruled from 1870–1940. The proximate cause of the riots was the uncovering of a massive embezzlement scheme by Alexandre Stavisky that bore more than a passing resemblance to the Bernie Madoff affair. At the time, the New Yorker described it as follows:

The scheme which finally killed [Alexandre Stavisky], his political guests’ reputations, and the uninvited public’s peace of mind, was his emission of hundreds of millions of francs’ worth of false bonds on the city of Bayonne’s municipal pawnshop, which were bought up by life-insurance companies, counseled by the Minister of Colonies, who was counseled by the Minister of Commerce, who was counseled by the Mayor of Bayonne, who was counseled by the little manager of the hockshop, who was counseled by Stavisky.

Perhaps some lonely historian at the Sorbonne on that cold day in 1934 reflected on how different this popular uprising was from the one which, some 147 years earlier, had led to the burning of the Royal Wallpaper Factory, the erstwhile Titonville, and the storming of the Bastille.

In the poster, Doreau attacks Frot for unmentioned crimes relating to the February 6 Crisis, making it clear that he believes his record to be contemptible, that he lacks both a backbone and an agenda, that he is a political opportunist of the worst sort. It is the language of an agitator and ideologue, to be sure, but also of an idealist. Doreau is carrying on the fight that was started on February 6, 1934, to bring down the left center government. While the Parti Agraire would be placed on the right or far-right of the political spectrum, they probably weren’t directly agitating for monarchy at the time (the right wing had been grouped under the Independent Republicans, which included the Parti Agraire, and the far-right Republican Independents, who probably were monarchists. You can picture the Monty Python’s Life of Brian moments when they ran into each other.) An article in Time Magazine advances some interesting speculations about our M. Frot in a March 19, 1934 entitled “FROT PLOT” (years ago all headlines were New York Post headlines):

In the Chamber of Deputies, a parliamentary committee of investigation began to dig into the more vital question of who was responsible for the bloody rioting of Feb. 6— in particular, who ordered the troops to fire on the mobs. Promptly came charges and counter-charges to make a Frenchman’s hair curl. Dapper Jean Chiappe, deposed Prefect of Police, faced his onetime Minister of the Interior, saturnine, black-bearded Eugène Frot, and baldly charged that M. Frot had been planning a coup d’état of his own to overthrow the Government; that he had organized an armed gang; that he had approached Raymond Patenotre, U. S.-born Cabinet Under Secretary, for a subscription to help arm this private bodyguard; that he had attempted to win over a Lieut.-Colonel de la Roque, president of the semi-Fascist Crois de Feu organization; that Premier Daladier had been warned of the Frot plot and had replied: “I have not unlimited confidence in M. Frot, and I knew already what you have just told me.” M. Frot brushed all this aside as “a rather amusing detective story.”

Already during this, the last election held during the Third Republic, Bernard Doreau, had written a novel under the pen name “Max Dorian” entitled Le Sextant, ou Un civil chez les marins. In fact, at the time of the hanging of this poster, he was probably in negotiations to publish his second novel (this time with Gallimard which would have been an exciting step up), Le comte de Buenos-Aires (1937). It’s romantic to think that he fled France, the “saturnine, black-bearded Eugène Frot” fast at his heels, to disappear into his nom de plume, with only a baguette and a broken set of Le Parnasse François tucked under his arm. I wonder, though, if his career as a writer of fiction died here with his idealism. In a few short years it was going to become extremely difficult for an educated, thoughtful, Frenchman to support the right wing.

Doreau/Dorian wrote only one more novel, Trinidad (1946), and then commenced a sort of second career as a cataloger of American enterprise. In succession he wrote: Du Pont de Nemours; de la poudre au nylon (and Du pont de Nemours : de la poudre au nylon : sélection photographique with his photographer and wife Dixie Reynolds); Un bordelais fut le premier millionaire américan; Voilà Wall Street : par Max Dorian et Dixie Reynolds, ce qu’il faut savoir du marché financier américain; and, with a few scholarly books in between, DuPont de Nemours from the Histoire des grandes entreprises series.

Remember, the DuPont chemical company was founded as a gunpowder mill on the Brandywine Creek outside of Wilmington, Delaware, and profited off of every post-Revolutionary war in the United States’s history. Maximilien Titon de Villegenon made a substantial part of his fortune and name from the introduction of small arms to the French military during his time as general manager of the armoires under Louis XIV (even our author, Évrard, great patron of the arts that he was, made a living for some time as “Police Chief of Wars”). In Dorian’s note, above, he writes of “la science au service de la mort”, an observation that could be applied to either or both of them.

Put end to end on a shelf, Dorian’s later works form a sort of Parnassus of American business — an ode to the genius not of the arts, but capitalism. Starting with DuPont, manufacturers as they were of gunpowder, chemicals, the building blocks of a thousand, thousand products, Dorian distilled success to its purest, American, form. Wall Street, the millionaire, the folklore of the dollar. It’s lovely in its way, this abstraction of success, raising of an edifice to the very essence of capitalist genius, like the French chef who ordered fifty hams for a feast, one for the meal and the other forty-nine to provide essence for his sauces. You can put this sort of sauce on anything.

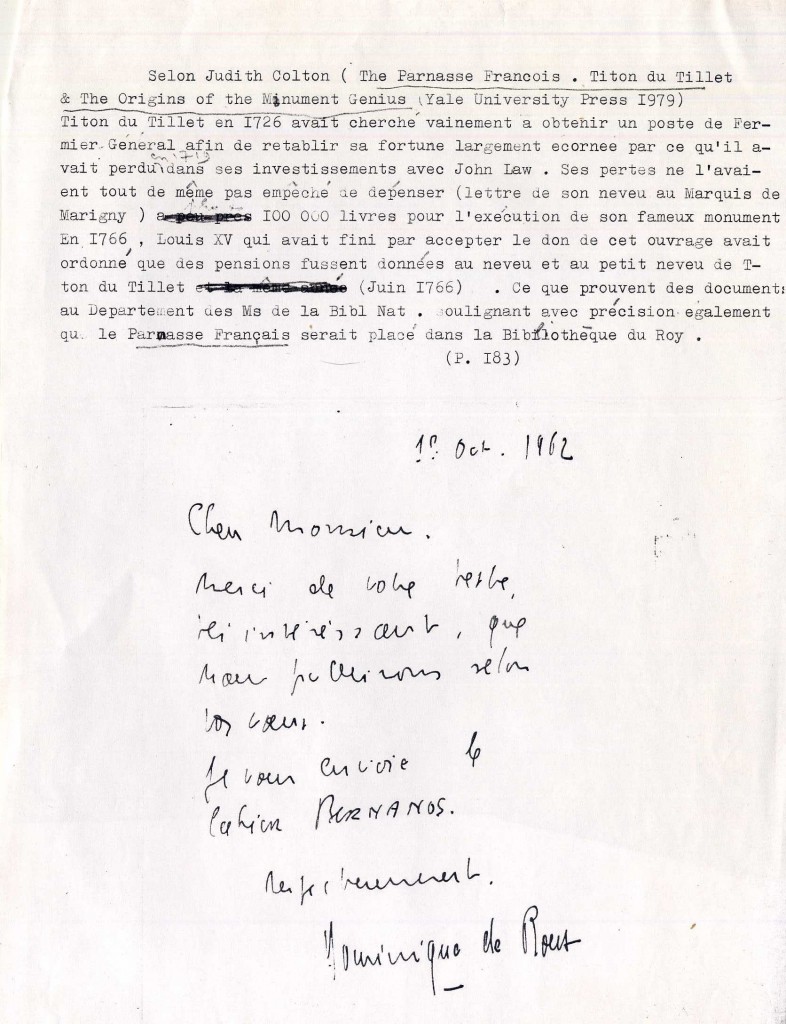

In the notes that Dorian took on Judith Colton’s The Parnasse François: Titon du Tillet and the Origins of the Monument to Genius (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979), he reports that Titon de Tillet had attempted, but failed, to obtain a post as Ferme générale, a sort of import/export tax collector. He had lost all of the money that he needed for his Parnasse on John Law’s Mississippi Bubble (a bubble more exciting, but more complicated, than the Dutch tulip craze, and the first of many on this side of the Atlantic), and needed some steady, lucrative, employment to put his Parnasse scheme together.

Some few questions remain: Where is the missing middle volume? Was it lost to the Terror? To right wing marauders; to Germans; to Frot and his center-left beard? When did the books first make their way across the Atlantic? Apparently Doreau/Dorian’s son lives in Massachusetts, and his papers were auctioned off a few weeks after these books, so we could dig further (his wife and collaborator, Dixie, died just last year at the age of 102!) but I think I’ve woven enough concentricities. It made it to Boston, anyway, and that’s not nothing. From Titon du Tillet, to Villotran; Nemours to Doreau to Pazzo — an impressive journey even absent the Royal Wallpaper fiasco, the French Revolution, The Terror, Napoleon, two World Wars, and a Skinner Auction.

It’s appropriate that we end with a poem, perhaps not worthy of Parnasse, but supplied by Max Dorian, née Doreau : “il goba le poisson mais n’en profita gueres car le chien lui cassa les reins” — roughly: he gobbled the fish but did not profit much by it, as the dog put an end to him. Capitalism, genius, French politics.

THE GOLDFISH

The goldfish loitered in her jar

and looked through the glass,

yawning at its masters consumed by their dinner.

Feigning indifference, a cat was sitting

watching the fish with darting blue eyes.

The dog was eyeing the cat. The alabaster clock

kept time and in the hearth,

a tidy fire sagely devoured

some branches.

That man is an idiot and his wife is stupid,”

said the solitary fish, exasperated;

“I’d give a lot to no longer have to look at their heads.”

The gods, whom we believe deaf, listened this time

To the fish we call mute.

The wish was granted, her masters went away,

but not the cat who kept watch.

He gobbled the fish but did not profit much by it

as the dog put an end to him.

The flame, roaring, threw itself on the dog

on the carpets, walls, curtains, windows:

everything went the way of the masters.

As it had nothing more to assuage its hunger,

The fire devoured itself in the end.

You know it is not a good tale

without a moral. Mine has two, here they are:

First: in this world it seems that if

our right to be free

leads us to demand FREEDOM,

a master, whatever it may be, merely keeps the balance

which allows us to enjoy it.

Second: To have peace in the household,

have neither cat, nor dog, nor fish… And before you go to bed,

it’s good practice to put out the fire

and thus pass your nights without fear…