Of Tablets, Holy Writ, & Holy Grails

By:

January 4, 2010

The mere possibility of an impending announcement of a tablet from Apple has tech journalists everywhere abandoning their cynicism for bouts of credulity and wonder. But the sudden zeal with which many commentators anticipate the Coming of the One may have less to do with Apple’s popularity than with our longstanding fascination with the idea that the written word might be made to dance and speak. It’s bound up in the mystique of Holy Writ — in the tangible, durable Word from on high — this time delivered in a handy format.

The search for a tablet “computer” is almost as old as the concept of computing — and the goals of would-be inventors of automatic writing machines are not unlike those of Charles Babbage, the grandfather of computer science (whose difference engines were not only experiments in machine calculation, but also automatic, error-free printing). What follows is a quick, partial chronology of tablets, notebooks, and automatic writing devices. The list below is fragmentary and partial; I’d be pleased to learn of other devices that fill out the timeline.

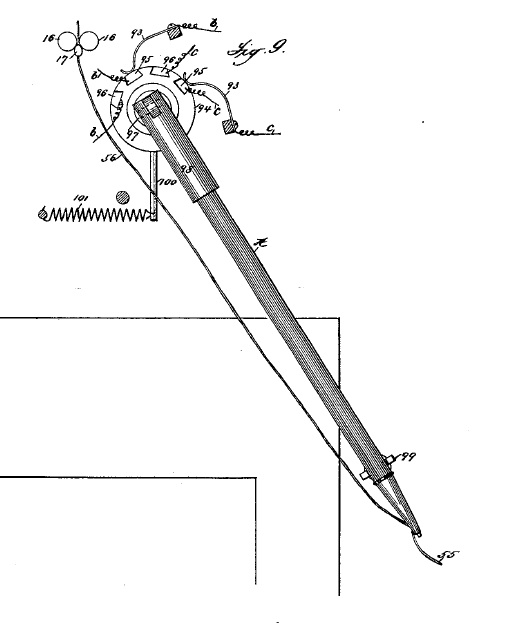

1888 | The Telautograph: stylus 1.0 (beta)

Leaving aside various automata engineeered to ape writing, the Telautograph, patented by Elisha Gray in 1888 (no. 386,815), is an ideal starting place for the story of automatic writing.

Gray’s stylus interacted with wires that crossed at its tip to send telegraphic pulses to a remote “receiving pen” driven by motors, which reproduced the writing (or drawing, or scribbling) made by the operator of the “transmitting pen”— which was charged with ink and furnished with paper as well, for the convenience of the operator who would want to see the characters he was forming for transmission.

Others (Alexander Graham Bell included) had produced similar apparatuses in previous decades. Gray’s, however, solved some key problems — notably, his receiving pen could write on a stationary pad, rather than a scrolling sheet or rolling drum — and his telautograph became a stepping stone to teletype and the fax machine. Versions of the telautograph were used for “instant messaging long after more suitable technologies came along —Wikipedia reports a telautograph in use as a kind of graphic intercom at the Triangle Shirtwaist plant at the time of its infamous fire in 1911, and a telautograph is depicted as the output device of an automatic translator in the 1956 film Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers.

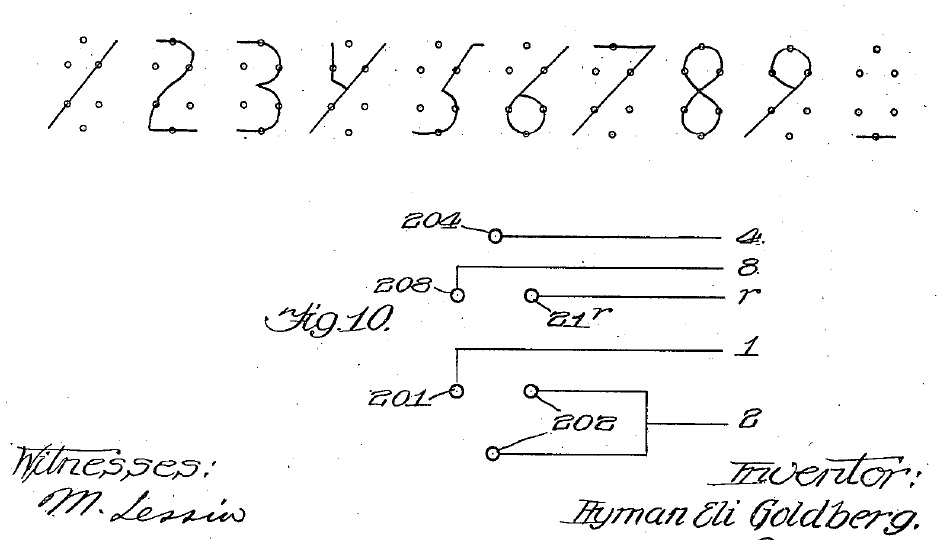

1911 | The Controller: writing the machine

Gray’s device was nifty, but it was merely intended for transmittal; no processing or actuating was possible. Eli Goldberg’s 1911 Controller (patent no. 1,117,184) offered an interface by which an operator could feed numerical data or commands to any device requiring an input including printing plants and other industrial machinery. Rather than employing keys, Goldberg’s system was graphical: the operator wrote stylized numerals in conductive ink across a matrix of electrical contacts.

The 1960s | RAND Tablets & Spark Pens: Styluses in Space

The desire was strong, however, to teach a machine not merely to reproduce or reat to script, but to understand it. In the 1960s, RAND researchers produced a slew of patents pertaining to various schemes for “Handwritten Character Recognition Apparatus”; “Recognition of Handwritten Numerical Characters for Automatic Letter Sorting”; and the like. The resulting device, the so-called RAND Tablet, with a grid of wires embedded in a “writing” surface to detect the motions of a magnetized stylus, was a watershed in so-called “pen computing” and the prototype for many commercial devices (including the Koala Pad, designed for the Apple II, which could receive the input not only of its stylus, but — a harbinger of things to come — bare fingers as well).

Sketchpad (below), meanwhile, developed at MIT in the early 1960s, paved the way for the CAD systems that would transform architecture and engineering.

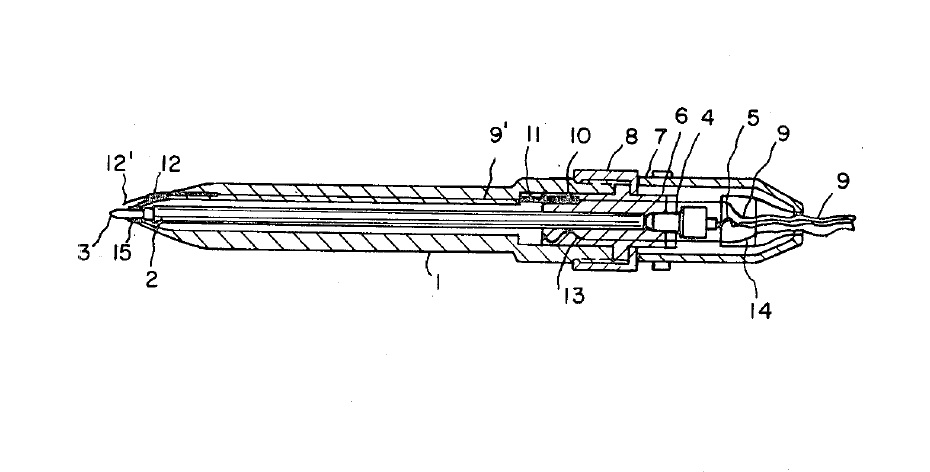

Less well known, a withered branch on the evolutionary tree of tech, is the Spark Pen (1971; patent no. 3,626,483), which consisted of a stylus with a spark plug at the business end. The crackle of the current as the operator “wrote” was captured by an array of sensitive microphones which could process the acoustic signal to track the nib’s precise location in space, translating it into pulses reproducible on a computer screen.

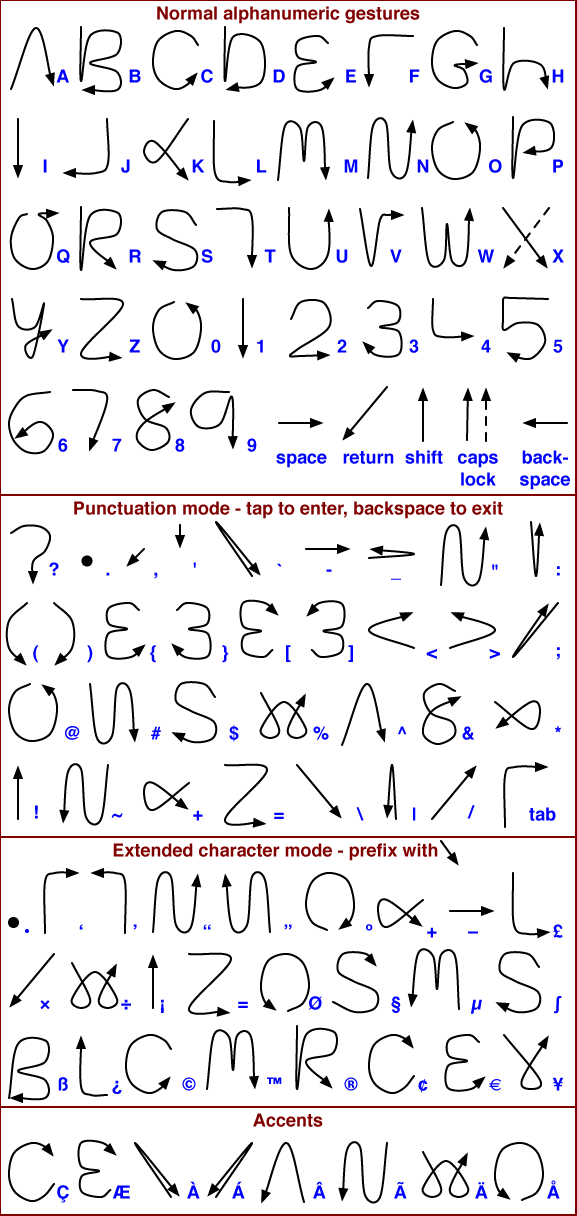

Ca. 2000 | Graffiti (Palm OS): Electric Shorthand

Jeff Hawkins devised a system for conveying graphic characters in a form comprehensible to the operating system of palm pilot PDA. While Graffiti is primarily remembered for its characteristic alphabet, the notable innovation was a system allowing the operator to enter glyphs one atop another on the same tiny pad, which the system would sort out and line up in legible order.

Graffiti was the target of intense intellectual property dispute between Palm and Xerox, which in 1997 had patented a similar system called Unistrokes. On appeal, Xerox’s claim was rejected because, in the words of the ruling, “prior art references” (e.g. shorthand) “anticipate and render obvious the claim.”

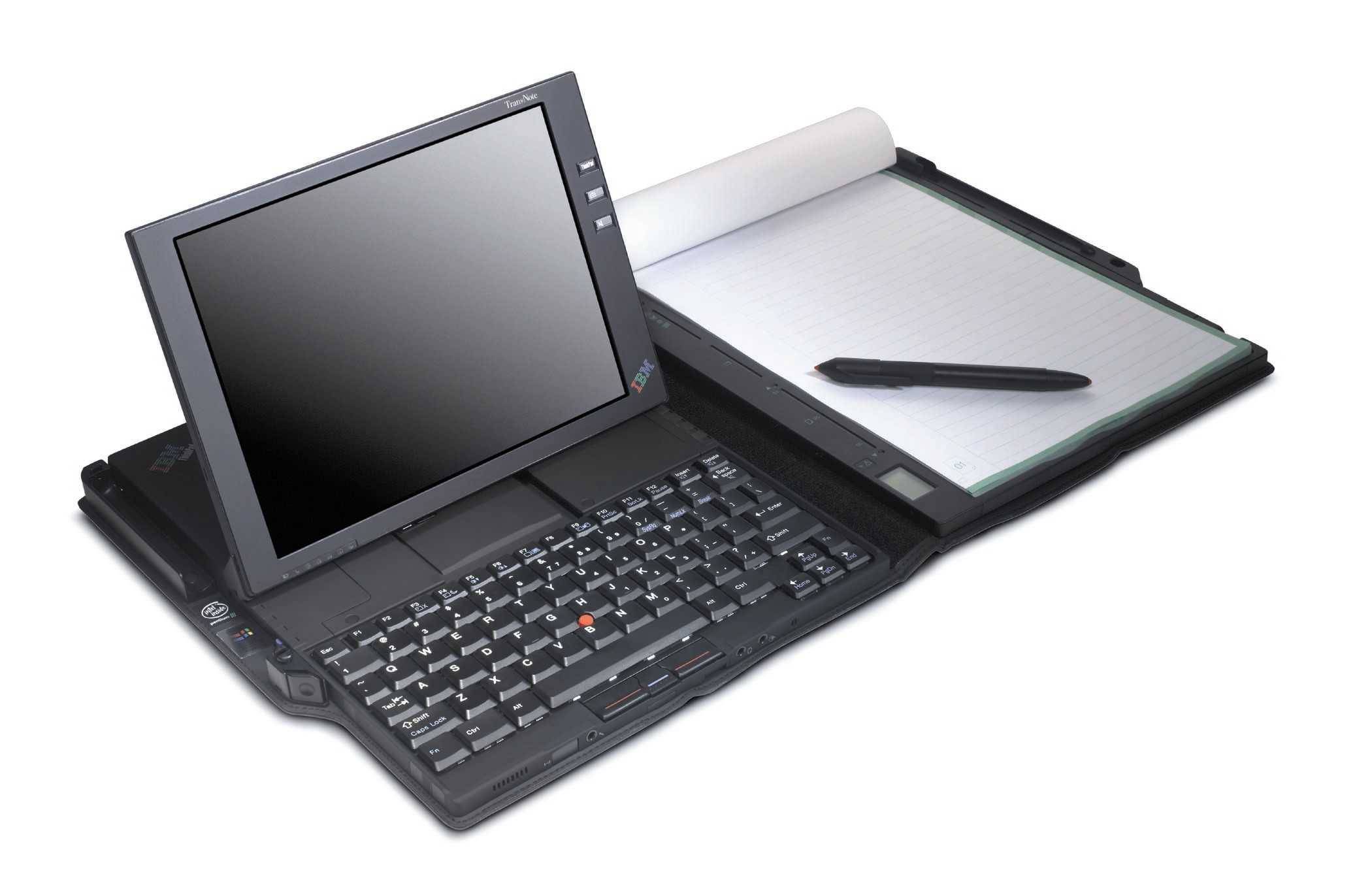

2001 | The ThinkPad TransNote: Folio Computing

Deep in the era of CapitalLettersWithoutSpaces, IBM introduced the TransNote — a portfolio consisting of a swivel-screened laptop computer on the verso side facing a paper notepad on the recto side. Inserted into a holster was a stylus with which one could write on the paper and have the motions captured in a graphics file saved on the laptop. The system included a rudimentary handwriting recognition system, but it never really worked. You could use regular legal pads, but the computer couldn’t keep track of the pages unless you numbered them and told it which sheet you were writing on (IBM sold paginated pads as fillers). In 2001, it was BusinessWeek’s “Best Product of the Year” and the winner of PC Magazine’s award for technical excellence; by 2002 it was gone.

Of course, today we have graphics tablets and capacitive touchscreens that are highly refined input devices and beautiful displays. And even the most hardened tablet skeptics recognize that a truly marvelous Apple Tablet is already among us in miniature, in the form of the iPhone. And the promised device will likely be as special, and as alluring, as its small precursor has proven itself to be.

Writing to our computers as if they are partners in an epistolary romance, long the holy grail of electrical engineering and computer science, is a goal that has receded in significance — largely because handwriting itself has ceased to be the primary means by which we record and convey words. It’s a problem solved not by fixing it, but by leapfrogging it. And so the tablet beckons; its promised advent makes our beloved laptops seem clumsy, our iPhones too small, our nooks and Kindles too specialized and limited. The very idea of a tablet computer, the butt of jokes until quite recently, now appears in the guise of the savior of publishing and the apotheosis of personal computing. I am eager to see it and use it. And yet I wonder — for after all, the tablet in its new guise seems less a tool for doing than for viewing. Nor will it be the first technology that promised to be the last.