Sugarplum Squeampunk

By:

December 11, 2009

The following brief scholarly notice I have sent, in agitation, to an ever-extending list of major decorative, biological, occult, literary, theosophical, hobbyist, and psychiatric academic journals. I commend the editorial wisdom of HiLobrow.com in seeing fit to publish this notice in its present form, for its pleasingly ornamental character, and perhaps as a warning to the world. The Manichean struggle between high and low — old as the snake’s entry into the Garden — is equally properly regarded as a constant, somewhat hideous eruption of “Elder Brows” into our placid, day-to-day sphere of middlebrow, so-called “existence.” But already I digress.

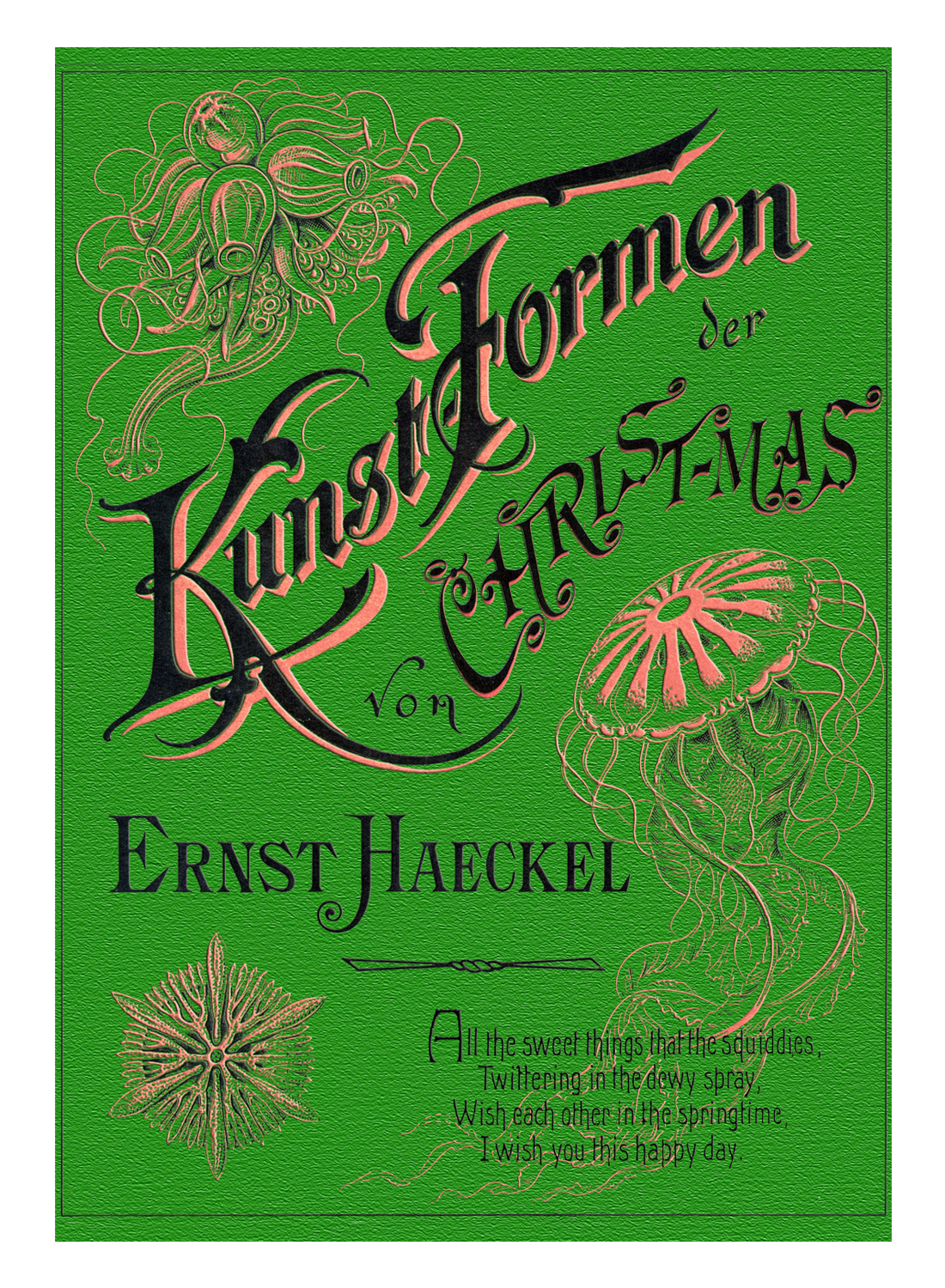

Last year I introduced the world to the fruits of preliminary research conducted by myself on the early works of Ernst Haeckel. Let me begin by rehearsing those findings:

Ernst Haeckel’s 1904 Kunstformen der Natur [Artforms of Nature] is a classic of biological illustration. What is less generally known is that the artist started as a Christmas card designer. The book was originally simply an album of holiday designs.

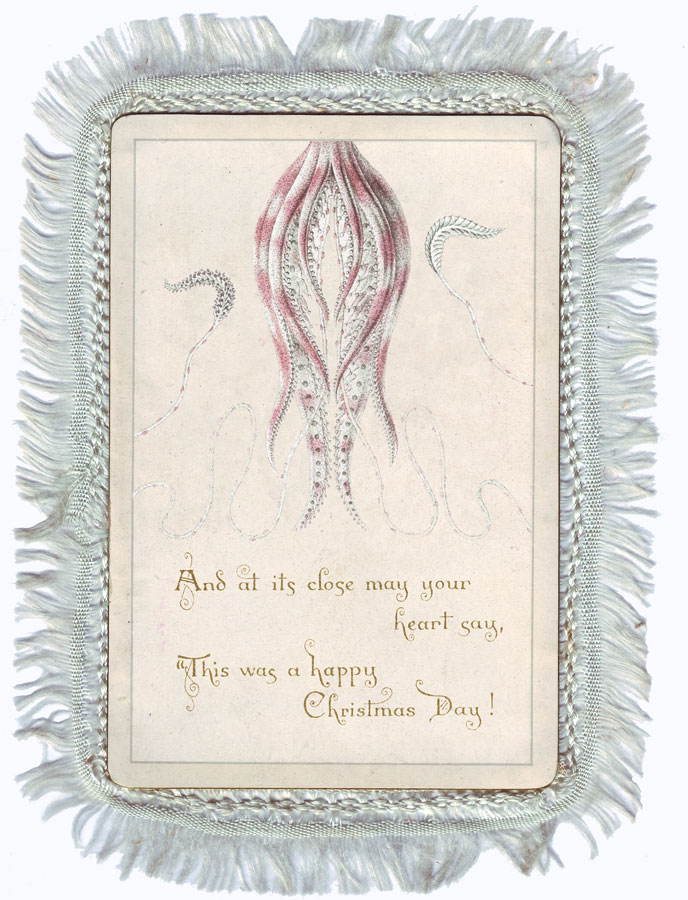

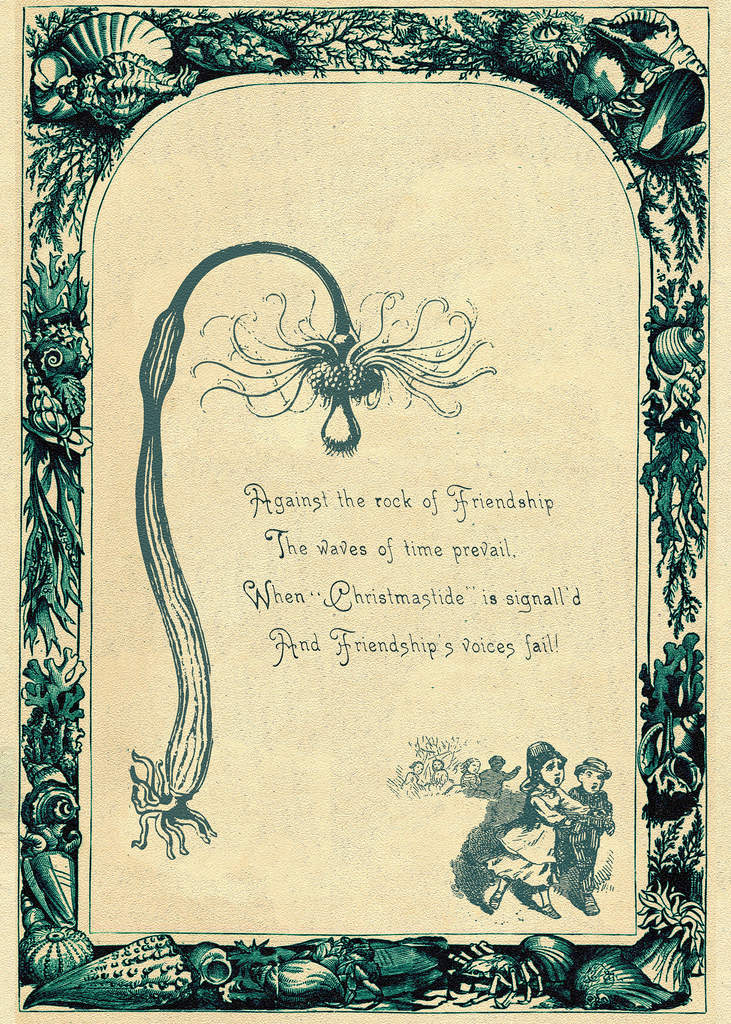

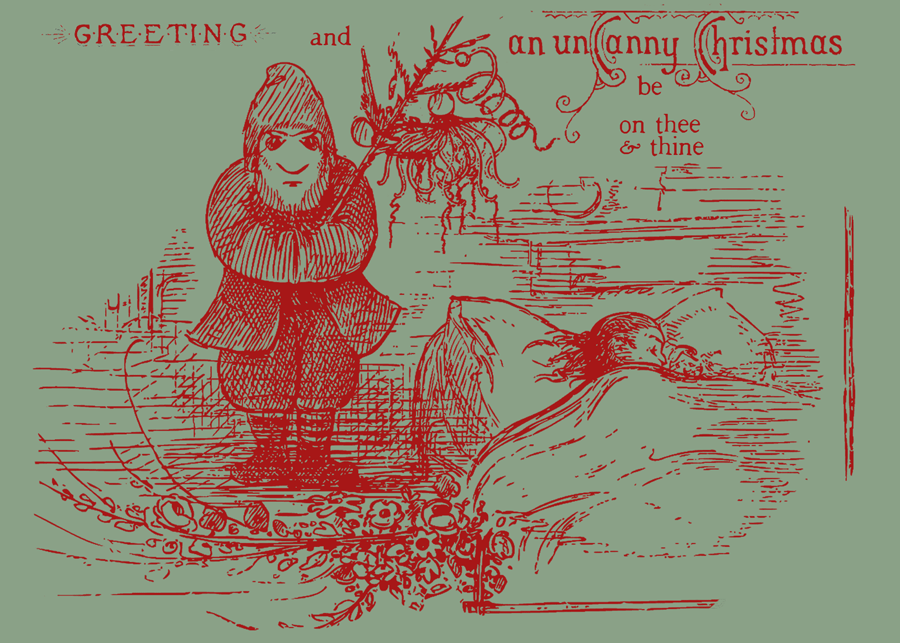

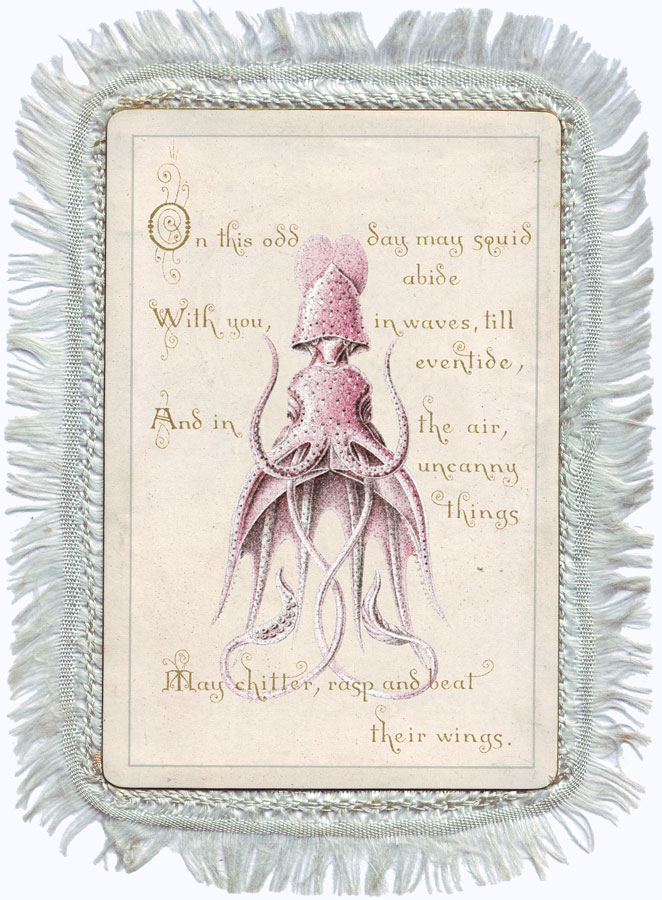

During the Victorian era Christmas was indeed regarded as a “happy” day, but one of uncanny terror; accordingly, cards and ornamentation featured strange creatures with too many tentacles. But then “Santa Claus” became popular, and many of these older designs fell out of fashion.

Commercially marooned, unable to draw anything except tentacles and congeries of pustules/bubbles, Haeckel repackaged his work as Kunstformen der Unnatur, to small notice. Finally, he wandered into “natural” science — almost as an afterthought. Isn’t that interesting?

Yes, it is interesting, if I may presume to answer my own question. It is interesting, as well, to note how many of the most basic features of Victorian morals and manners have languished, uninvestigated — indeed, undreamt of — to this day. Our universities suffer no dearth of self-styled “Victorianists.” No doubt that leering monkey called ‘lack of intelligence’, set to capering by the ill-tuned hurdy-gurdy of common human concourse, and more suited to the chasing of pennies than the discovery of truth, has played its part in preserving the discovery of many hidden things from this scholarly herd. True, the advent of critical tools of scholarship necessary for this project — notably, eBay and Photoshop — needed more “advanced” technologies (if that is the word). But I digress again. My purpose here is to report fresh findings.

Haeckel’s early Christmas card designs proved not the end of my investigative line but — as is so often the case with Haeckel!— the start of another even more writhing thread. He worked, for a time, for a London firm, Raphael Tuck & Sons, allegedly founded by a German immigrant in the mid 19th Century. This “common knowledge” is subject to doubt. Tuck House was razed during a Christmas-time blitz, in 1940, but whether German bombs could have been responsible for curiously “shadowless columns of flame”— to quote an eyewitness account by a London civil defense worker — is likewise subject to doubt. Was “the mad Cherub,” as Tuck was known, for his designs and demeanor, really Raz-al Tariq, or a descendant of that notorious “Mad Arab”? The question begs an answer. Was “Tuck” a corruption of “Puck,” “the oldest Thing in England,” to quote Kipling’s admittedly fanciful and pretty-pretty accounting of that elder Entity. Tuck, the man, could hardly have been Puck. But perhaps there is a lineal link to stories of greeting cards traded at Solstice, before the time of the Romans; of cards as old as Stonehenge, even dark hints that Stonehenge itself is but a collection of “greeting stones”? I leave as an exercise to the reader the consideration of the implications of the latter thought!

Again I digress! The predominantly tentacled and be-pustuled designs favored by the Victorians — designs Haeckel was preeminent at rendering, through the superlative collaboration of fevered brain and steady pen that distinguished him — were collected, aesthetically, under the heading “squeampunk.” The term is apparently an overstuffed portmanteau of “squaymous,” as in Chaucer’s Miller’s Tale: “He was somdel squaymous/ Of fartyng, and of squide daungerous”; and “pank”, or “fang,” meaning to be fixed or made firm. Beowulf is, famously, described as “squaympanked” by Grendel’s mother. (But whether that means she bit him or merely struck terror, is a question for linguists and forensic archeologists.) Squeampunk, as an aesthetic movement, gave ground over the course of the 19th Century, in the face of increasing taste for “cheerful” designs among the urban masses, and increasing industrialization — the romance of the machine, if that is no strict contradiction in terms. As James Watt declared, in his defense of the new aesthetic, “steampunk” was needed because, “we cannot hope to achieve knowledge of, let alone harness the power of, so-called ‘Old Ones’, the least thought or sensory apprehension of which must drive the human mind to the edge of madness. But we can bloody well boil water!”

Artifacts have lately come into my possession, long rumored to exist, shedding no little light on the subterraneous links between the comparatively young holiday of “Christmas,” as we know it, and the eldritch roots of Victorian squeampunk. I have acquired a complete set of the so-called “necro-gnome icons”— cthulithographed, gaily uncanny trading cards that were “terrible and forbidden,” banned by church and crown, hence highly collectible and prized by Victorian housewives and children, who assembled them in decorative albums for display. One such set, apparently passing through the (not regularly washed, I should judge) hands a small boy named “Gilbert” has, as I said, lately come into my possession.

From this set I have been able to draw a considerable stock of fresh deductions. The necro gnome is — the reader will leap to what is indeed the true conclusion — father to our Jolly Old Elf. But, scientifically speaking, it will not do to regress physiognomic Santa into some purported Ur-necro-gnomic horror by simple transformation of beard into tentacles, etc. There is but one word for the products of such procedures: plausible. Plausibility is not science. The truer line is tangled, fraught with false association and coincidental resemblance (bane of the followers of mere plausibility.)

Conventional depictions of a bearded, rosy-cheeked St. Nick derive from Victorian depictions of Sog Nug, or Soggy Nick, or Soggy Ned — a silent and frog-like little gnome said to “paddle in the stream of dreams.” (Not to be confused with Shaggy Nuk, whose name is a corruption of an Esquimo term for what is presumably a North American sasquatch or, possibly, some sort of wendigo.) As the child’s poem runs:

Paddles the stream of dreams.

Teaching you this lesson True

No Thing is as it seems.

Soggy Ned was pressed into service by practitioners of the Victorian “Science of Sweet Dreaming.” To encourage children to dream “only of the good,” they should to lectured before bedtime that, if they did, Ned would bring them toys and good things. But if they did not, their nightmares would become reality. Specifically, they would find their own nightmares in their socks, in the morning.

—

As an instrument of moral improvement, Soggy Ned was of uncertain utility. But the gnome secured steady employment on a more limited, annual basis, becoming a Christmas icon from which certain of our own ritual practices plainly derive.

So that is how we get from Ned to Santa, in a nutshell. But whence Soggy Ned itself? These collectible “icons” provide the key. Their story, insofar as I can piece it together, is as follows. In the offices of Tuck and Sons worked, for a time, a young “formularist,” or “cthuligrapher,” by the name of Albert Wedge-Wheskit (of the literary Wedge-Wheskits). It was the job of these young men (and women — many of the best were female) to discover brief formulae that would act efficaciously on the human nervous system, stimulating potentialities that might otherwise lie dormant. Some of the most successful of these formulae are known to this day: Merry Christmas! Happy New Year! Sometimes the formularists would pen short poems that appeared on the cards the company sold. The formularists favored decorative letterforms and what seem to us — though impressions are not to be trusted — highly ornamental designs.

Wedge-Wheskit delved too deeply in his researches. If I may quote from The Fringes of Madness— a substantially apocryphal, anonymous account of the card designer’s career, but one containing important insights: “there is no small distance between the gay wallpaper designs of a bright, cozy sitting room and the dark, empty spaces behind the stars.”

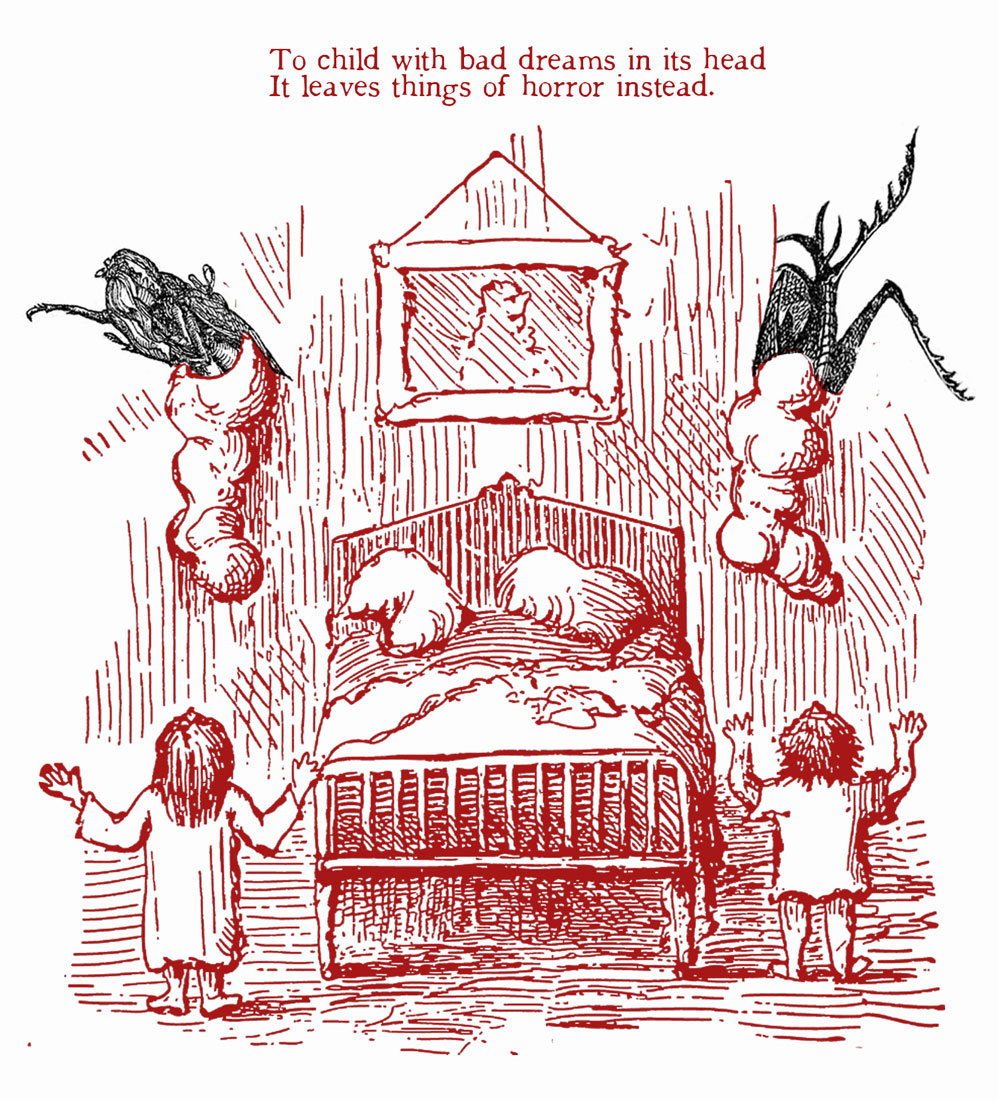

Wedge-Wheskit favored dark designs, even by the standards of the Victorians. Here are a few samples of early work, done in collaboration with Haeckel.

—

—

During the night before the Christmas morning on which Wedge-Wheskit was carried off to the asylum, in 1852, leaving behind a weeping wife and hysterical children, he apparently banged out the designs for a series of six cards, in a frenzy of Victorian sensibility. (He screamed “legs and ligatures, the hideous ligatures!” most piteously, according to an orderly who assisted in restraining the patient.) Tuck and Sons commissioned their man, Haeckel, to add extra legs. Sales were as brisk as the creator’s madness ran deep.

Without further ado, I present these rare cards to the world of scholarship.

A VISITATION OF SOG-NUG-HOTEP

T’was the night before C’thrishm’sh,

when all through the House

What a Creature came stirring,

all legs, wings and mouths.Ancient words had been read

from an old book with care,

In hopes that Sog-Nug-hotep

would not come there.The children were trembling

under their beds,

While visions of Elder Gods

danced in their heads;And mama in her ‘kerchief,

and I in my madness,

Had just hunkered down

with foreboding and sadness,When out on the lawn

there arose such a howl,

I sprang from the bed

to see what was so foul.Away to the window,

faint hope of escape,

Tore open the shutters

and drew back the drape.The moon on the breast

of the new-fallen snow

Gave an uncanny luster

to objects below,When, what to my lunatic eyes

should appear,

An unspeakable sledge,

and eight Things to strike fear!With a tentacled driver,

so slick in the fug,

I knew, to my horror,

it must be Sog-Nug.More rapid than eels,

its limbs whipped the air,

And it gibbered and moaned,

whispered names of pure terror.“Now Dh’ashoshoth! Now Dh’azathoth!

Now Prhathulu and Vozothun!

On K’baa! On Cthul-Nug!

On Dhrul-nur and Blas’atlun!To the cold of the stars!

From which doom must fall!

Now smash away! crash away!

dash away all!”As limbs of the dead,

too freshly inhumed,

Push up through the earth,

and refuse to be tombed,So up to the house-top

the shoggoths they flew,

With that sledge full of dread,

and Sog-Nug-hotep too.And then a great weight

I sensed press on the ceiling,

The sliding and gliding of tentacles

… feeling.As some force froze my will,

made me tremble and quail

Down the chimney Sog-Nug-hotep

slid like a snail.Such impossible shapes

seemed to make up its frame

For which no geometer

has any name.Its eyes — filled with darkness;

its pustules, how many?

Its body was hidden —

did it even have any?Yet behind there were Things,

seething darkly and heavily

Mortal brain must refuse

to regard such sights levelly.Could the uncanny mass of it

be protoplasm

That shook like a jellyfish

suffering a spasm?It was made of such stuff

as is not of this earth

And I howled when I saw it,

for all I was worth;A blink of its eyes

that put thoughts in my head,

Soon gave me to know

I had Old Ones to dread.At this point there is a gap in the manuscript. I must have fainted and lain insensible for a time — how long, I know not. Upon awakening, in darkness, the moon having set, I would scarcely have credited my fantastic, already fading memory of these terrible events, save that I found the following lines among my fevered yet decorative designs, written in my own hand, the second couplet in a tongue unfamiliar to me, despite all my scholarship.

As it left I still heard,

like the voice of a dragon,“Ph’nglui mglw’nafh C’thr’ishm’sh

R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn!”

What conclusions can we draw? First, there is no gnome in these “necro gnome icons,” from which we may confidently deduce the series title referred to no elf, but to a necrognomic — that is, death-knowing— entity, the terrible Sog-Nug-Hotep, awakened or summoned in the course of Wedge-Wheskit’s occult greeting card researches; which the designer then failed to ward off on the tragic night in question. Perhaps it was merely a case of heightened consciousness: the designer over-sensitized to things that exist alongside ourselves, undetected in the course of our everyday existence by our dull sense organs. (There is precedent for such cases.)

It seems undeniable, as well, that this Sog-Nug must be the long sought ancestor of Soggy Ned/Sog Nick, hence of St. Nick — our Santa Claus. Necrognome became — if the reader will permit a feeble witticism — a thorough mis-gnomer! The partial representations of Sog-Nug on these cards resemble nothing so much as terrible Christmas trees. I think we can infer that two familiar holiday fixtures —Santa and the decorated tree — were once a single entity. The figure of Soggy Ned already gives hint of this with the “festoon of fir and jellies” which he is invariably depicted as bearing: half-remembered aspect of Sog-Nug and ancestor of our Christmas tree.

I think we can conclude as well that H.P. Lovecraft drank deeply from the dark well of these cards — how not? And that Clement Clark Moore’s supposed publication of “A Visit From St. Nicholas” in 1823— more than a quarter century before Wedge-Wheskit designed these cards — must be something on the order of a massive hoax. That poem simply could not have been written before these cards were created. I do not presume to be able to explain how the hoax was perpetrated. No doubt “experts” will retort that Moore’s poem argues, to the contrary, that it is this allegedly rediscovered card series of mine that is the forgery here, from which I evidently seek to profit in some tawdry way. Would that it were so! For my part, I keep my conscience clean, even at the cost of a besmirched reputation!

Visit John Holbo’s Cafepress Store, or homepage, for all your Sog-Nug swag and Haeckel Holiday goodies!