Winds of Magic (10): Agent Zimmerman

By:

November 15, 2009

I had just removed his hand — gently, I hope — from my knee when the man in the off-white linen suit told me that he was the one who recruited Bob Dylan into the CIA. The bar was desolate but warm: outside was a Chicago winter like a bear roaming the streets. I’d come to town to interview a garbage man/mobster, and it had not gone well. In fact, I was terrified. So now, with my new buddy beside me, I was drinking like a brain surgeon in the middle of a nervous breakdown.

“The CIA?” I said. “Well, that’s interesting.” I took a swallow of Jameson. “That might even be, you know, sensational.”

His large eyes, glossy with the effects of the four Long Island Iced Teas I had watched him consume, searched mine. It was a long search, to the point where I wondered if perhaps he had simply fallen asleep with his eyes open, like certain gifted tribesmen of the Amazonian basin.

“Your unreflective skepticism,” he said at last, with the ponderous dignity of the totally tanked, “is a tribute to the most daring masquerade of our times.”

“You mean — ,” I began, but was silenced by the raising of a pink, ringed hand.

“Bob Dylan was a spy,” he announced. “A very great spy. And I was his spymaster!” Now he was glaring at me in a kind of rude nostalgic triumph.

The bartender, who’d been stacking glasses, sighed heavily. Like it or not, this story was going to get told.

“Please,” I said. “Go on.”

“How can I convey,” said the man in the bar, relaxing now, “to one as cherubically unlined as yourself, the great anxiety of the 1950s?” The creases in his jacket exhaled a complex, blossomy booze-and-cologne aroma — comforting, in its way. “Above us was the white crack of infinity. The Bomb. Annihilation! But beneath us the ground was shifting, too. Beatniks, Communists, sodomites.”

“Sodomites?”

“Bongo-players,” he continued. “Philosophers, nudists, tap dancers, Jesus freaks, red-wine drinkers. We in the Company had our eye on all of them. We knew better than they the strength of their contempt for society. But from where, precisely, would the threat to order come? From the existentialists, or from the vegetarians? Our great dread was that these various distracted factions would eventually…” (And here he had a small, fragrant coughing fit.) “…would eventually coalesce and form a movement.”

“Horrifying!”

He ignored my sarcasm. “So we decided to find their leaders before they did. Simple enough. We penetrated them. We went into their stinking smoke-filled coffeehouses and their rank little nightclubs. We endured their revolutionary sing-alongs and their tambourines and all that ‘Go, man, go!’ crap. Christ, I don’t know how many times I heard Ginsberg read Howl. We went in heavy. Saturation. By 1958, I’d say the ratio of undercover Company men to genuine bohemians in Greenwich Village was about two to one.”

“But… wasn’t this sort of FBI territory?” I ventured. “Domestic surveillance and such?”

“FBI!” He snorted unpleasantly. “Would a G-man learn how to play the dulcimer? Take classes in the dulcimer, for six months? Deirdre!” He hailed the reluctant bartender. “Deirdre! Another Long Island Iced Tea, if you would. Thank you, sweetie.”

“Dulcimer classes?”

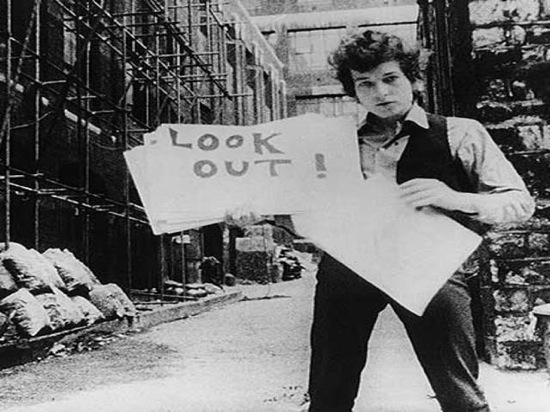

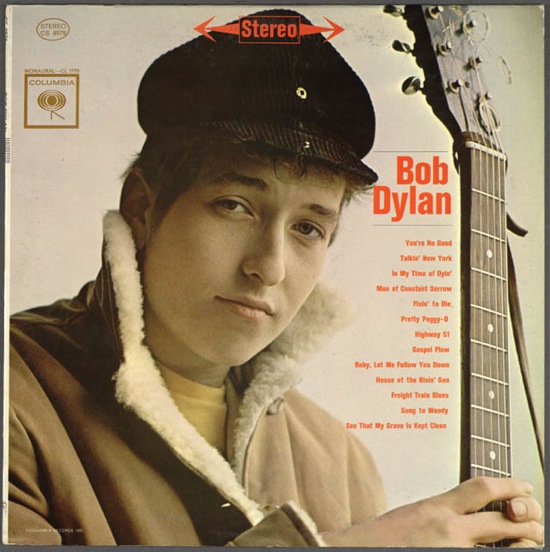

“You bet your ass. I was in a medieval folk trio called Tyme Out of Mynde. Tyme Out of Mynde, with y’s where the i’s should be! That’s sacrifice, pal. That’s doing your duty. But you know, when I first saw Zimmerman in the Cafe Wha?, right there things began to get wonderful.”

“He was — ”

“Oh, he was a graceless little monkey then, of course. Tobacco-stained fingers, chubby cheeks, no manners at all. And that voice! Like Woody Guthrie left out in the rain for a week. And such silly-billy music he made at first, all about being an old boxcar-jumper with holes in your hat. So derivative, so false! But, you see, that was the whole point.”

Now I was interested. “What was the whole point?”

“He had no identity! None! Just this greedy, untethered intellect slipping about in the realm of myth and symbol. Like a dreamer, but wide awake. I couldn’t have imagined better conditions for the creation of a first-class artistic spy. Can you see the magic of it? He wanted an identity, and I had one ready for him! He would be the bard, the Pied Piper. He would take all of this shambling, up-all-night disaffection, this shapeless totality of kooks and bums and hedonists, and lead it right into the river. Ha!” He slapped the surface of the bar, and I nearly fell off my stool. “So I put him on the payroll.”

“But — but what did he do for you?”

“What did he do?! Good God, man, listen to the records! He hypnotized them. Under my instructions, of course. ‘Be more enigmatic!’ I’d say. Or: ‘Be more Biblical! Be more like William Blake! Speak to their souls! Make them feel like the end of the world is around the corner! And whatever you do, keep the scorn in your voice.’ Well, he was a natural for that kind of work. He was a very well-read boy. Thank you, Deirdre my darling.” He slurped at his fresh drink.

“But what about, you know, the chimes of freedom flashing and all that? ‘The answer is blowin’ in the wind’?”

“Decoys. In order to fully subvert the pitiful earnestness of the times, he had to partake of it now and again. Incidentally, the best line in ‘Tambourine Man’? ‘To dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free’? That was mine.”

“And when everyone booed him? When he went electric — what was that?”

“Ah! He loved booing. It was like champagne to him. On that tour of Europe, all skinny and heavy-lidded, while everyone howled — marvelous. That was Phase Two: Disorientation.”

I was feeling a little disoriented myself. “I still don’t get it,” I mumbled. “The Voice of a Generation…. The People’s Poet!”

“All of those things, yes, yes,” he sighed, swilling his cocktail in its glass. “We succeeded so spectacularly it almost frightened us. But I kept my eye on the details. I planted men in press conferences to ask him particularly dunderheaded questions. I said to him, ‘Write something about the president taking his clothes off — the kids will eat that up.’ If he’d told them to knock over the White House, they would have done it. But he didn’t, did he?”

“I suppose not.”

“No, he led them into the river of poetry, where politics dissolve…. Oh, Bobby, Bobby…” His eyes were half-closed and his head was sinking over the bar. It was time for me to go. As I opened the door and felt the paws of the winter upon me, I could hear him begin to mutter, like one enchanted, from “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” — those looping, sinister, voodoo phrases.

I didn’t look back.

Originally published by The Boston Phoenix on November 20, 2007. From 2003-08, our friend and colleague James Parker, currently a contributing editor at The Atlantic, was a culture critic for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section and for Boston’s alt-weekly, The Phoenix. HiLobrow.com has curated a collection of Parker’s writings from this period. This installment is the tenth in a series of ten.